Let’s take our very first look at the top-scoring translations of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone!

At the time this post was written, just under 30 editions had been rated on the Spellman Spectrum, a scale designed to rate and compare translations of the same text. That’s a pretty sizeable amount! But it also leaves us less than a third of the way through the long list of translations of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, while the Spellman Spectrum itself remains a work in progress. So expect to see revised postings of this list—perhaps once or twice a year—until the list is complete.

With that said, we can already see a broad range of ratings along the scale! Only 2 have surpassed a score of 90 (Norwegian and Maori), while 3 (French, Dutch, and Frisian) have reached a score of 80. Luxembourgish falls just short of 80 and the remaining books fall within a wide range of 22–77. So let’s take a quick look at these top-scoring translations and highlight a few things in each one! Keep an eye out for full articles on each of these editions in the future.

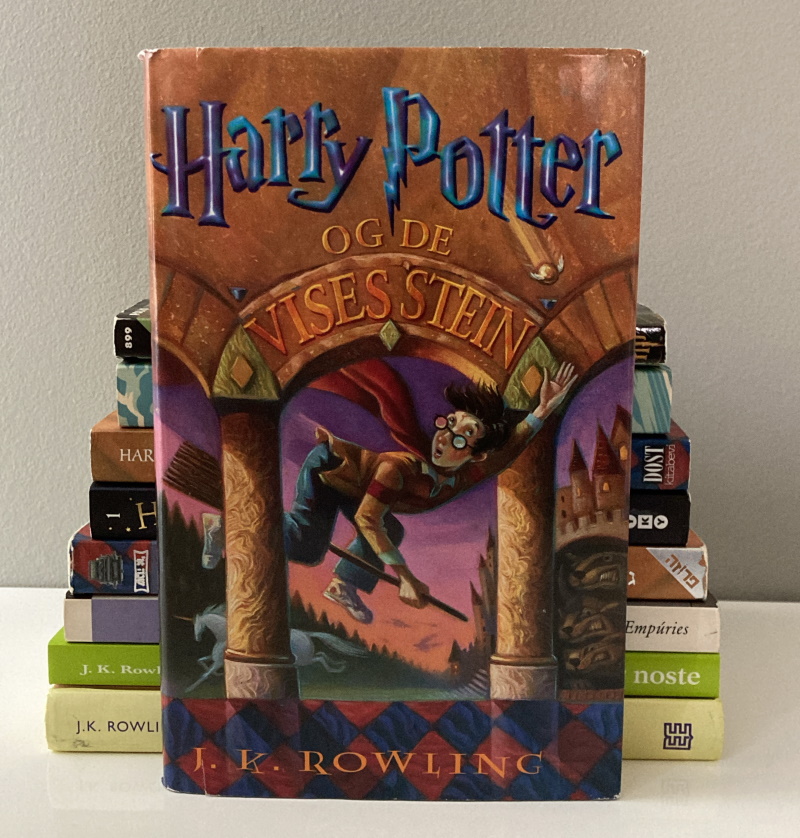

1. Norwegian: Harry Potter og de Vises Stein

What I love about this particular translation is how nicely it flows and how it creates so much humor of its own. Any gomp (non-magic person) who has gone through this translation has certainly enjoyed their visit to “Galtvort,” the magical school headed by Albus Humlesnurr and his deputy Minerva McSnurp! Be prepared for Gnav the Poltergeist, whose japes are as comical as the Norwegian game he’s named for.

Of course, coming up with clever names is not nearly enough for a good score. (Scots scored just 65.0 on the Spectrum!) The overall text flow and the humor of the translation are some of the most enjoyable I’ve seen so far. In many cases it’s even better than the original English! I can’t help but see Mrs. Dursley’s pucker-face when the narrator describes Dudleif, som var verdens aller nudeligste (“Dudley, who’s the most cutie wootie in the whole wide world”) on the opening page.

It’s no surprise that the Norwegian translation is so impressive. Its translator, Torstein Bugge Høverstad, is well-seasoned. Aside from Harry Potter, he has translated a tremendous amount of English-language fantasy and science fiction, including Lord of the Rings and Dune, as well as Charles Dickens (known for his vivid imagery and caricature) and Toni Morrison (whose illustrious writing style depends heavily on both syntax and word choice).

2. Maori: Hare Pota me te Whatu Manapou

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was translated into te reo Māori (a Polynesian language in New Zealand with somewhere between 50,000 and 200,000 speakers) at the initiative of the Kotahi Rau Pukapuka Trust. Its purpose was to engage people in Maori literature and culture using a familiar tale.

It succeeded. I have yet to see a translation that has inserted as much local flavor as the Maori edition. The image you get in your head of the wizarding world changes entirely as you imagine, for example, potions brewing in a kōhua, a traditional Maori oven. The translator, Leon Heketū Blake, went so far as to research Maori incantations (karakia) to influence his translation, although I have not yet found how that bore fruit in the translation. To be determined…

The neologisms were brilliant: truly new but also comprehensible. “Fantastic Beasts” is kātuarehe (“cunning rascals”). “Transfiguration” is mata huri (“changing face”). “Vampire” is kaitoto (“eats blood”). My favorite is the translation of Slytherin, Nanakita, which plays on three words: nanakia (“treacherous, crafty”), naki (“glide”), and kita (“fastly”).

As I mentioned in a previous post, Maori is one of only a couple translations in the world that, to me, satisfactorily translates the first sentence of the novel. It did so by using an idiom of indignation native to Maori. Blake did a fantastic job translating the book into an enjoyable and Maori-oriented context. You can tell his heart was really into the mission of the Kotahi Rau Pukapuka Trust, and that motivation helped make it one of the top-scoring Harry Potter translations.

3. French: Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers

The French translation is so original that even the title was changed: Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers (“Harry Potter at the School of Sorcerers”)! That title is an indication of just how much freedom Jean-François Ménard had when he did this early translation in 1998. For whatever it’s worth to add, translators after 2000 were not so free.

So much freedom in fact that he literally added to the story in some places.

When they first meet on the Hogwarts Express, Ron mentions his brother Percy is a prefect. Then he moves on immediately to describe his brother Fred and George.

But in the French edition, Harry interrupts:

– Préfet ? Qu’est-ce que c’est que ça ? demanda Harry.

– C’est un élève chargé de maintenir la discipline, répondit Ron. Une sorte de pion… Tu ne savais pas ça ?

– Je ne suis pas beaucoup sorti de chez moi, confessa Harry.

“Prefect? What is that?” asked Harry.

“It’s a student charged with maintaining discipline,” Ron responded. “A pawn of sorts… You haven’t heard of it?”

“I don’t get out much,” Harry confessed.

Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers (Jean-François Ménard)

That exchange, explaining what a prefect is at the same time Harry’s learning all the other new wizarding world concepts, is entirely absent from the English edition, where a prefect is a typical part of the British schooling system. Instead, you’re left with the impression that prefecture is a feature unique to wizarding schools.

Overall, Ménard had quite a bit of fun wherever he could. This might even be the only translation where Hogwarts, Hogwarts, Hoggy Warty Hogwarts reads just as fun: Poudlard, Poudlard, Pou du Lard du Poudlard. His ability to maneuver as he wanted was key to making one of the best translations of the Harry Potter franchise.

4. Dutch: Harry Potter en de Steen der Wijzen (and Frisian: Harry Potter en de Stien fan ‘e Wizen)

The Harry Potter series was brought into Dutch by the same translator who did A Clockwork Orange… and you can tell! The Anthony Burgess novel is notorious for its frequent interspersion of Russian and Russian-derived words, whose meanings the reader must infer using context. That requires a skilled translator: the translator must construct an inferable context in the target language, or the reader will be lost.

With such attention paid to individual words and phrases, it’s no wonder that Wiebe Buddingh’ opted to translate nearly every proper noun into a Dutch context. The first thing he considers when translating, according to this interview, are the names and puns. Hogwarts becomes Zweinsteins, Neville Longbottom becomes Marcel Lubbermans, and even Ron Weasley becomes Ron Wemel. Diagon Alley (a pun on “diagonally”) becomes Wegisweg (which can be interpreted as something like “Off to the Wayside”), a nice pun in Dutch playing off Weg (“Road,” used in street names) and tightened by alliteration. In the broader consideration of Harry Potter translations, the fact that Buddingh’ did not translate Newt Scamander might indicate the strong resolve of the Warner Bros. to market the Fantastic Beasts brand internationally, even before the film series was conceived. (Can anybody with a pre-2000 edition check for us whether the name was translated in early editions? EDIT: According to Harrison, the pre-2000 Dutch editions had Spiritus Salmander rather than Newt Scamander.)

An interesting cultural phenomenon is found in the names Albus Perkamentus and Draco Malfidus. Perkamentus is Latinized Dutch (from Dutch perkament, “parchment”) and Malfidus is just plain Latin (“Bad Faith”). Centuries ago, many elite families in Europe took on Latinized surnames and the presence of those Latinized surnames remains particularly pronounced among the Dutch today. This lends a sort of aristocratic feel to Albus Perkamentus and Draco Malfidus, which, frankly, is quite fitting for those characters and their families.

You probably noticed in the headline that I included the Frisian translation by Jetske Bilker. It scores nearly as high on the Spellman Spectrum as the the Dutch translation. But I chose not to treat it separately because it seems to have been translated into Frisian directly from Dutch (although it clearly consulted the English original as well). Thus the Frisian score is artificially high because it relies on many of the structural components that gave Dutch such a high score. Still, Bilker took a poetic approach of her own and does deserve credit for some of the score.

5. Luxembourgish: Den Harry Potter an den Alchimistesteen

This book received a surprisingly high score on the Spellman Spectrum for a translation I would consider more source-oriented and relatively literal. For those collectors who prefer translations that are unique but keep the original names, this might be the high-scoring book for you! It’s easy to see why it scored so high, though, especially considering how one-of-a-kind written Luxembourgish can be.

The translator, Florence Berg, made some very clever interpretations. We see that immediately in the title of both the first book (Alchimistesteen, “Alchemist’s Stone,” referring directly to Nicolas Flamel) as well as the second (Salazar säi Sall, “Salazar’s Hall,” referring to the Chamber of Secrets). Another fun title is that of the Beginner’s Guide to Transfiguration, which becomes the Abécédaire fir Verwandlung (“The ABC’s of Transfiguration”).

Concluding thoughts

There you have it, the top 5 (or 6?) translations of the first 30-some editions rated on the Spellman Spectrum: Norwegian, Maori, French, Dutch (and Frisian), and Luxembourgish!

Have you had the chance to read any of these? If so, leave a comment with your thoughts about the translation and what aspect you enjoyed the most!

1 Pingback