Asturian is a language you’ve probably never heard of. Unless you’re a history buff, a Spain aficionado, or, well, a Harry Potter collector. The Romance language, spoken in the northwestern autonomous region of Spain called Asturias, has only 250,000 speakers, of whom less than half likely have native proficiency. But it has an absolutely fascinating history!

There aren’t many brief introductions to Asturian online, so I thought I’d offer a little tour de la langue here at Potter of Babble. I’ll start below by outlining a few of the similarities with Spanish, followed by some of the differences. Then I’ll continue with a brief history of the Asturias region and its language, interweaving its history with that of Spanish. Then I’ll end the post with some frequently asked questions and a brief list of resources for learning more.

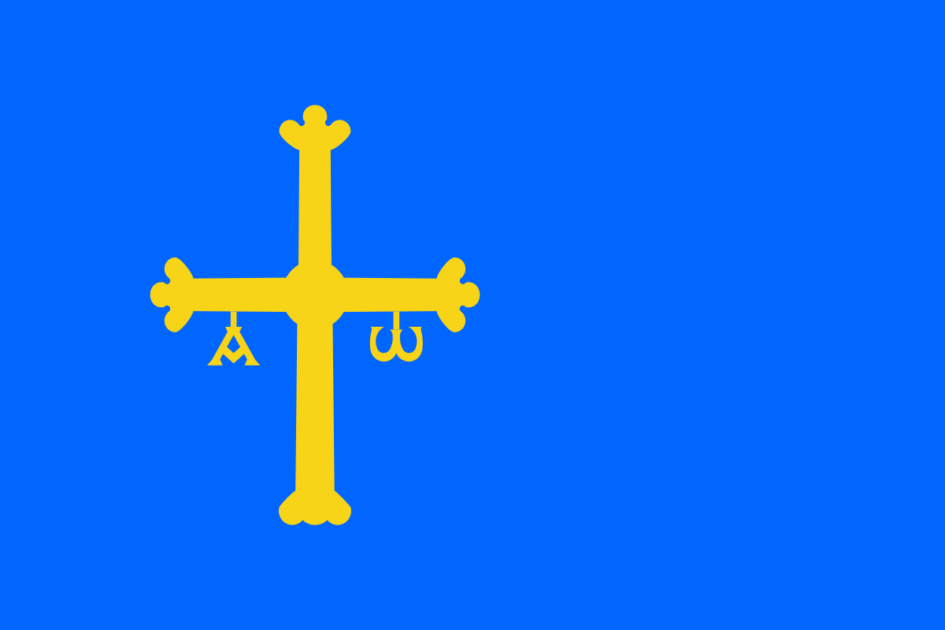

ㅤ

Features that Distinguish Asturian: Selected Examples

ㅤ

Central Asturian, the standard variety, shares some glaring features with Spanish that are usually considered distinctive:

- “Breaking” of short e and o: piedra and puerta (compare pedra and porta in Portuguese)

- Forms of the definite article “the”: el, la, and lo (although lo is used differently in Spanish)

- Changes to words like Latin clamare (‘call’), clavem (‘key’), and pluviam (‘rain’): llamar and llave and lluvia (vs. chamar and chave and chuvia in Portuguese)

But Central Asturian is also distinguished by a number of differences. Some of those differences reveal features inherited from Latin but were lost in Spanish:

- Masculine nouns end in -u in the singular: cuerpu (compare Spanish cuerpo; a conservative retention from Latin’s masculine accusative case, –um.)

- Feminine nouns end in –es in the plural: vaques (compare Spanish vacas; possibly a retention of Latin –es in the 5th Declension?)

- Neuter nouns (neutru de materia) end in –o. (A retention of the Latin ablative case.)

- These mark collective or generic nouns and cannot take a plural form. Compare el pelu roxu (‘the strand of red hair’) versus lo pelo roxo (generic ‘red hair’).

- Retention of f at the beginning of a word: facer (compare Spanish hacer)

Others differences were once shared with Spanish, but have since been lost in Spanish:

- Retention of x pronounced as ‘sh’ (in Spanish merged with j to become ‘h’ in the 15th century): dixo (compare Spanish dijo)

- Retention of pronominal objects at the end of conjugated verbs: tráxome la comida (compare Spanish me trajo la comida)

Asturian has also had some innovations of its own:

- More widespread breaking of e and o than in Spanish:

- Before ‘y’: güei (compare Spanish hoy)

- In the verb ser: ye (compare Spanish es)

- Change of ‘h’ to ‘g’ before ‘ue’: güevu (compare Spanish huevo)

ㅤ

The Story of Asturian, and How Spanish Took over Spain and the New World

The historical claim to fame of the Asturias region is as the birthplace of the Reconquista. Histories of Asturias typically begin with the 8th century, when the Arab-Berber conquests of the Iberian peninsula caused the collapse of a decaying Visigothic kingdom. The power vacuum allowed the peninsula to be taken over in a rapid sweep. Under the leadership of a warrior called Pelayo (Pelagius), the region of Asturias successfully resisted the invasion, aided by the natural barrier of the Cantabrian Mountains and becoming one of the only corners of Iberia where Islamic rule would never take hold.

ㅤ

ㅤ

ㅤ

The forces of Asturias established a garrison in Oviedo, atop a hill surrounded by mountains, and consolidated the region into the peninsula’s first Latinate kingdom since the fall of the Roman Empire. The Asturians had kept many of the customs of the Romans, produced literature in Latin, and likely spoke a primordial form of Romance. Spanish historiography has long held a dynastic continuity from the Visigoths to Pelayo and his successors, but that claim is highly suspicious. In all likelihood, the new kingdom of Asturias was no more Visigothic than the Arab-Berber caliphate in Córdoba was.¹ Still, there is no doubt that Asturias became the formative cultural and linguistic link between modern Spain and the late Roman era.

Asturias reached its zenith with Alfonso III, who is remembered in Spanish history as “Alfonso the Great.” The Catholic king had launched a successful assault against the Muslim invaders, pushed them out of their northernmost territories, and sent Christians from Asturias to “repopulate” the captured lands (which, it should be noted, had been predominantly populated by Christians anyway). The expansion was well-regarded back home, not least because the capture of resourceful land brought wealth and prosperity to Oviedo’s rugged terrain. Alfonso III thus set the stage for the Reconquista and, many centuries later, the dominance of the Romance languages over the whole of the peninsula. The expansion had at last made Asturias prosperous, and securing the city of León was its greatest prize. After some wrangling among Alfonso’s sons, the kingdom’s capital shifted to León.

Securing the city of León was the greatest prize of Alfonso’s expansion and, after some wrangling among his sons, the kingdom’s capital shifted south to that city. It was during this period that the earliest documents written in Iberian Romance begin to appear. A 10th-century list of cheese and the 12th-century Fuero d’Avilés are among them, and many have reasonably argued that they more closely reflect the language of Asturias than the language of Spanish.²

Omne poblador de Abiliés quanta heredat poder comparar de fora, de terras de villas, seía franca de levar on quesir, é de vender, é de dar, et de fazer de ela zo qu’il plazer; et non faza per ela neguno servitio.

Excerpt from the Fuero d’Avilés

A man living in Avilés, as much property as can be bought from outside the towns’ lands, will be free to take wherever they want, to sell, to give, and to do with it as he pleases; and without doing any service for it.

ㅤ

With the epicentre of the kingdom shifted south of the Cantabrian range and more exposed to the Arab-Berber forces, the kingdom’s eastern frontier grew in importance as a buffer zone. Sparsely populated in the 10th century, that eastern region known as Castile was heavily fortified (hence its name from Latin castella, “castle”). Concentrating the kingdom’s military might far from the kings’ oversight proved destabilizing, though. By the end of the century, Castile was autonomous. And in the 11th century, Castile began to dominate. In the 13th century, the dynastic lines of León and Castile merged through Ferdinand III, the first-born son of the king of León and the infanta of Castile.

ㅤ

ㅤ

ㅤ

As León’s king and court were incorporated into the court of Castile, the kingdom saw a shift from the Asturian language to the Castilian language as its predominant dialect of Romance. Documents ceased being written in Old Asturian soon after as business was increasingly conducted in Castile. It was the Castilian language (castellano), the dialect of Iberian Romance spoken by elites in Castile’s capital of Toledo, that later became the language of government and the lingua franca of the Spanish empire: Spanish. The Old Castilian dialect was very closely related to the Old Asturian dialect in León, and they were so mutually intelligible that they were not likely considered separate languages at the time. But Castilian had undergone some distinctive changes not seen in Asturian. Among them was the change of f– to h– in words like in forno (Castilian horno). Moreover, the cosmopolitan dialect of Toledo, which had been under Arab rule for centuries, had imported a significant amount of Arabic expressions.³

Amid its ascent, Castilian eclipsed Asturian in literary output. Efforts in Toledo to standardize the language of government, especially from the reign of Alfonso el Sabio (Alfonso the Wise) on, formally stamped out Asturian as a written language. As far as we know, nothing was written in Asturian in the 14th and 15th centuries. Meanwhile, the Castilian epic El Cantar de mio Cid, an older composition in pre-Castilian Romance that nonetheless reflected the ethos of the Castilian dynasty, was coming into its final written form.

ㅤ

ㅤ

In its expansionist phase, the kingdom of Castile carried out an aggressive form of cultural imperialism (at its peak, the Spanish Inquisition), making it necessary for anyone upwardly mobile to assimilate and embrace Castilian as their language. It did not, however, aim to stamp out other languages and dialects entirely, and several languages throughout Spain, like Asturian, survived as minority languages. As the dust settled on Castile’s domination of Spain, however, Asturians began writing in their local tongue again in the 16th century.

ㅤ

ㅤ

The oldest extant text in modern Asturian, Pleitu ente Uviéu y Mérida pola posesión de les cenices de Santa Olaya, was written in 1639 by Antón de Marirreguera. Why Asturian instead of Castilian? Well, as alluded in the title, the poem was entered into a contest of rhetoric to determine whether the relics of Saint Olaya (Eulalia), a regional patron, should be placed in Oviedo or Mérida. In the dialect of Oviedo, Antón wrote:

| Si nos lleven esta Santa No hay más d’arrimar la foz; Dirán ellos: Morrió acá; Diremos nos: Non morrió. Q’está viva par’Asturies | If they carry this Saint to us There will be no need to go down into the gorge They will say: She died there; We will say: She hasn’t died. For she is alive in Asturias. |

ㅤ

In these words we see a purposeful localism by Marirreguera. Not only did he make a powerful statement as to Saint Olaya’s importance to Oviedo over Mérida, but he drives it home by delivering it in Oviedo’s own form of expression.

Asturian expression began to flourish with the Spanish Enlightenment (of which the Asturian and statesman Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos was one of the most influential intellectuals). By the late 19th century we see clear signs of a linguistic awakening, with the publication of grammatical studies and compilation of dictionaries of the Asturian language.

ㅤ

At the same time, speakers of Asturian (frequently referring to their speech as Bable) became increasingly diglossic: using Asturian at home but Castilian Spanish in public. Industrialization and urbanization had brought many Asturians into cosmopolitan settings where Castilian Spanish was needed as the lingua franca. Not only did this diglossia relegate Asturian to the sidelines for many of its speakers, but many Asturians also began embracing the view that Bable was just a substandard form of Spanish.

In 1976, as Spain transitioned away from Francoism, the Conceyu Bable was born to advocate for the teaching of Asturian in schools. Four years later, it was replaced by the Academy of the Asturian Language. The Academy codified a standard set of spelling and grammatical rules for Asturian. With the support of the government, it helped cultivate a revival of the language, both literarily and educationally. In a positive turn for the language, a generation of Asturian youths gained a sense of pride and enthusiasm in using the language—a rarity among language revivalist efforts and a good sign for the language’s vitality. Asturian is now used in formal workplaces and classrooms, a stark reversal to its relegation to the mines and home. Because of its newfound support and prestige, the language is undergoing an age of renaissance, but with such a small community of speakers in such a big country, it remains to be seen how long that renaissance will last.

ㅤ

Frequently Asked Questions about Asturian and Spanish

What’s in a name? Bable and Castilian?

Asturian is often called “Bable,” a term of uncertain origin that may have once meant something along the lines of “everyday speech.” The term appears to be much older than “Asturian” and was the preferred term in the 1970s when the movement to revive Asturian first began. The term “Asturian,” which was first widely applied to the language in the 19th century, has grown in favor as the language has become increasingly associated with geographic location (i.e., spoken in Asturias) than with informal audience (i.e., friends and family instead of work and school). The term has been rejected by anti-leftists who assert that Spanish should be the sole language of Asturias; activists associated with El Club de los Viernes regionally and with Vox nationally tend to insist on the term Bable in effort to undermine Asturian’s legitimacy as a regional language.

Note that throughout the post I refer to Spanish as “Castilian” or “Castilian Spanish.” This reflects a distinction that’s actually made in Spanish literature itself: a distinction intended to highlight the fact that Spain is home to several closely related Romance languages, and the language known as “Spanish” has its origins in the Castile region.

Why isn’t Asturian considered Spanish?

Of all the Romance languages spoken in Spain and its environs, Asturian is the most like Castilian Spanish. Not only are they mutually intelligible, but Asturian shares a lot of phonological traits that are otherwise unique to Castilian Spanish. Vowel breaking of o → ue (puerta) and e → ie (piedra) is one example. Asturian has also borrowed a significant amount of vocabulary from Spanish. And to complicate things further, speakers of Asturian often engage in codeswitching between Asturian and Castilian Spanish. So it can be very easy for outsiders to mistake Asturian as just a substandard variant of Castilian Spanish.

But there are a number of reasons why it’s considered a separate language:

Asturian is “older” than Castilian. OK, this claim is misleading in a few different ways, but the exaggeration is meant to drive home a point. The first kingdom of Romance speakers in Spain was the Kingdom of Asturias, and it was out of Asturias that the first Romance texts came. The earliest preserved document said to have distinctive Asturian features, the Fueru d’Avilés (Act of Avilés; 1085 or 1155), was written in the 11th or 12th century. It was not until the late 12th century that documents portraying the vernacular of Toledo (i.e., Castilian) were written.

Modern Asturian retains old features that Castilian Spanish has lost. Or, for the more linguistically-oriented among you, Castilian Spanish has innovations not found in Asturian. The change of initial f– to h-, a distinctive feature of Castilian Spanish, never happened in standard Asturian.

Asturian may not be as closely related to Spanish as it appears. Some linguists, on neogrammarian assumptions, lump Asturian in a closer genetic relationship to Portuguese and Galician than to Castilian Spanish. But with the four West Iberian languages so close to each other, it’s difficult to say definitively whether this is true. Asturian may simply fall between Galician and Spanish in a dialect continuum.

Asturias is a distinct place with a distinct people. This reason may sound silly, but this is actually one of the most important factors in determining whether a language variety is a language or a variant/dialect: do the people who speak the language variety consider it a separate language? That’s usually enough to decide a variety is a separate language. If those people live within a distinct geopolitical boundary—such as the Principality of Asturias—that strengthens their ability to foster an independent literature, strengthening the claim that the language is separate.

ㅤ

Resources

Deprendi Asturianu – Lessons in Asturian Grammar (in Asturian, with references to Spanish)

Online Asturian-Spanish Dictionary – From the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana

Learn and connect – An old-school discussion forum of Asturian speakers. (As of the publication of this article in June 2023, the forum is active and the most recent post was in May 2023.)

A Linguistic History of Asturian – Not for the faint of heart. It’s a dissertation.

News in Asturian – The Asturies news site gives you new reading material on daily basis. Already know Spanish? Jump right in to these short articles and you’ll learn Asturian in no time!

Read the latest research on Asturian language and culture – Published by the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana

Buy books in Asturian – From publisher Ediciones Trabe

Varieties of Asturian – Introduction to the different dialects of Asturian (YouTube)

ㅤ

ㅤ

Footnotes

¹ It is often forgotten that the Arab-Berber invaders did not, for the most part, uproot the local populations—much of whom had collaborated with the invaders to overthrow Visigothic rule. The idea that the Asturian rulers continued the Visigothic line first appeared during the reign of Alfonso III “the Great,” as did the earliest surviving records of the Asturian dynasty.

Not coincidentally, Alfonso III engaged in a campaign to expand the borders of Asturias southward into Arab-Berber–ruled land. By claiming to represent the fallen Visigothic dynasty that the Arab-Berbers had toppled, he could justify his capture of territory as a Reconquista—reconquering land that the Asturians’ forebears, the Visigoths, had lost. (His Visigothic heritage was not all that he used to bolster support for his campaign, by the way: under his rule, Asturias became Roman Catholic Europe’s new Jerusalem after the bones of St. James had been allegedly found in Santiago de Compostela, more than 3000 miles from Jerusalem where he is said to have died.)

² The Royal Spanish Academy of Language includes these documents as the earliest examples of written Spanish. My expertise on this matter is limited. But since Asturian and Spanish continued to develop alongside each other as sisters during this period, it might be more accurate to say that these documents represent an ancestral form of both Asturian and Spanish. Indeed, the speakers of Old Asturian and Old Spanish probably considered themselves to be speaking the same language, which they interchangeably called by terms like romance, latín, fablar, and lengua. It is undeniable, however, that the center of culture at this time lay more in Asturias than in Castile, from whence Spanish was born.

³ Centuries later, most of those Arabic expressions were also brought into Asturian through Castilian. i’ve been careful to highlight the oft overlooked significance of Asturias and the Asturian language to the history of Spain and the Spanish language. But it must also be noted that Asturias and its language did not develop in a vacuum any more than Castile or its language. Although the Arabs minimally influenced the Asturian language before the 16th century, they did have a formative impact on Asturian identity and self-expression as early as the 8th century. Likewise, the Asturian language, which today looks nothing like the Latin that the Romans had brought to Spain, has been very visibly influenced by the Galicians to the west and the Basques to the east, and has introduced a number of innovations of its own. Thus there’s no veracity to the idea that Asturian represents a pure, unadulterated Romance—a view associated with the regionalist ideology known as Convadaguismo.

1 Pingback