One of the more difficult languages to find Harry Potter in these days is Urdu, a language mutually intelligible with Hindi that’s spoken in India, Pakistan, and even the United Arab Emirates. The original translation was done by Darakshanda Asghar Khokhar, apparently a housewife in Pakistan who wanted to make the immensely popular English-language novel available in Urdu. It’s no longer in print—possibly because English is widely understood in Pakistan, where Urdu is spoken by only 8% of the population. In other countries where people commonly read in English, like India or the Philippines, many of their Harry Potter translations have also fallen out of print.

A second translation, by Moazzam Javed Bokhari, has become more readily available in recent years. And while collectors tend to prefer the original Khokhar translation, the question has come up whether original truly is better.

So I’ve decided to visit that question in today’s post. Before beginning, I’d like to preface with a disclaimer. I have a lot of exposure to spoken Hindi, and I know Arabic, and this has helped me take a look through these two translations. But I don’t speak Urdu myself and its script is somewhat difficult from an Arabic standpoint, so I’m prone to make mistakes. Moreover, like Arabic, Urdu writing often omits vowels and I’ve had to fill in with some guesswork. So if you’re an Urdu speaker, I welcome your input and apologize in advance for any errors that have slipped through the cracks.

Both are source-oriented. And use English in Urdu script?

Now, what’s interesting in comparing the Khokhar and Bokhari translations is how similar they are in their fundamental approach. They’re both source-oriented and use a surprising amount of transliteration of English. The Hogwarts admission letter to Harry, for example, is addressed in both translations to “Mr. H Potter” (misṭar aich poṭar). For those aware of the history of Pakistan and India, you’ll know that the extensive use of English in these two translations reflects the lasting impact of the British colonial era in South Asia.

The Khokhar translation also leaves the name of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry untranslated, transliterating it instead: hogwarṭs askool aaf wizarḍree ainḍ wich kraafṭ. Indeed many private schools in Pakistan similarly retain English names. More striking, though, are the lack of translation for terms like “Sorting Hat” (sorṭing haiṭ), “Seeker” (seekar), and “First Years” (first ayeerz). Even the book titles on Harry’s school list are given in English (e.g., fainṭasṭik beesṭs ainḍ wayir ṭoo fayinḍ daim). Following the experience of many Urdu speakers (in both Pakistan and the United Kingdom), Hogwarts in Khokhar’s translation is very clearly an English-speaking school where English is the language of instruction and school activities are conducted in English as well.

Bokhari translates a bit more into Urdu. Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is hogwart skūl beraa’e jaawogaree opar asraar ‘uloom (“Hogwarts School for Witchcraft and Occult Sciences”). Vampire is translated as khoon ashaam bhoot, a term apparently imported from Persian literature. Cauldron is translated as kaṛahee, a flat-bottom style of wok specific to South Asia. Even Dumbledore’s favorite sweet is transformed into a sekanjabin, a refreshing honey-vinegar drink that’s also Persian in origin. Meanwhile, Khokhar translates goblin and troll into terms familiar to Urdu (boona, “dwarf,” and dev, a type of horned ogre), while Bokhari retains the English words for those creatures.

Both translations retain most of the proper nouns of the English, although Khokhar’s transliterations are much more simple. Bokhari is a bit more daring: wizarding world terms are more likely to be translated, like “Remembrall” (yaaddaashtee gaind), although the meticulous transliteration of names like Quirrell can lead to a mouth full (kyooryeel).

Khokhar is too plain; Bokhari is too literary

The Khokhar translation gets a bit overly simplistic or explanatory in certain places. Instead of translating “poltergeist” in some way, Peeves is glossed as a spirit that appears upon summoning. Sure, that’s an attempt to differentiate Peeves from other ghosts. But it doesn’t really capture either Peeves’ character or the meaning of “poltergeist.”

In a scene where, in English, Harry and Ron are roasting bread, English muffins, and marshmallows over the fireplace, Khokhar simply says they were eating really fun stuff. And when Snape gives his poetic introduction to Potions class—it’s a bit less inspired in Khokhar’s Urdu: I hope you can truly appreciate the beauty of this art. A cauldron boiling ever so slowly and the florescent smoke exuding from it. His voice is monotonous and droning by comparison.

Bokhari’s translation seems to have a more natural flow. But at times it seems awkwardly literary where Rowling had intended something more colloquial. Compare Khokhar and Bokhari on Peeves’ tease when he discovers Harry and friends out past midnight:

English original: “Wandering around at midnight, Ickle Firsties? Tut, tut, tut. Naughty, naughty, you’ll get caughty!”

Adhee raat ko awaarah gardee. Nanhe First Year baby, tut tut. Sharaartee sharaartee pagre jawu ge. Sharaartee.

“Midnight wanderers. Little First Year babies, tut tut. Naughty, naughty, you’ll be caught. Naughty.”

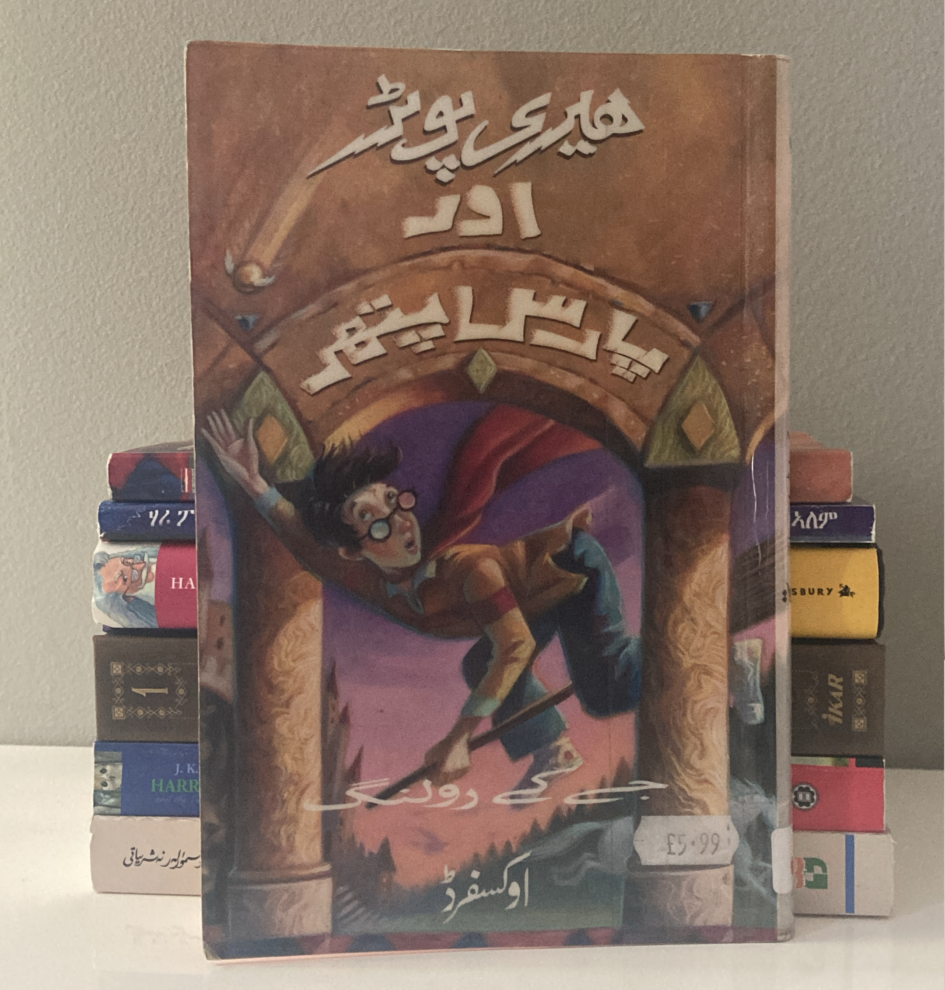

Harry Potter aur Paras Pathar by Darakshanda Asghar Khokhar

And here’s Bokhari’s Urdu, which has pleasant meter and rhyme, including internal rhyme, but is just too intricate and long for Peeves’ cutting jest:

Adhee raat ko baahar ghoom rahe ho,

saal awwal ke nanhe mane bacho!

He he he. Qavaaneen kee khalaaf warzee

pagṛe jaane se ḍaṛte bahee ho.“Out walking around at midnight, little first year children! He he he. Breaking the rules, scared of getting caught.”

Harry Potter aur Paras Pathar by Moazzam Javed Bokhari

And when Peeves is tattling on Harry and friends for being out past midnight, he demands Filch ask “Would you be so kind to tell me where they went?” rather than “Please tell me where they went.” In a similar vein, even Hagrid uses a more literary command when asking Harry in a letter to send a response with Hedwig than something more fitting for Hagrid.

Khokhar better captures J. K. Rowling’s intent

It’s perhaps Bokhari’s attempt to capture a more formal Urdu reading that also leads him astray when it comes to certain subtleties. When Harry approaches Uncle Vernon about the train to Hogwarts, Uncle Vernon reacts: “Funny way to get to a wizards’ school, the train. Magic carpets all got punctures, have they?” The colloquial phrasing in this line in English is designed to highlight how funny it is to get to a wizard’s school by train. “The train is a funny way to get to a wizard’s school” would be more grammatically sound, but that standardized phrasing would focalize the sentence around the train. Rowling deliberately chose to buck what’s grammatically appropriate because the more colloquial arrangement better captures Vernon’s attitude.

Khokhar’s translation catches this subtlety: ʿajeeb ṭareeqah he, jaadoogaroon ke askool pahunchane ka. rail gaaṛee se. “Weird way, that is, to get to a wizards’ school. By train.”

Bokhari’s translation changes the focalization to the train: rail gaaṛee se bahee koee jaadoogaroon ke skool meen jaataa he? baṛaa ʿajeeb ṭareeqah he. “Train, who goes to a wizards’ school by that? It’s a very weird way.”

While some readers wouldn’t be bothered by such subtleties, the Khokhar translation is simply more astute in that regard.

Concluding thoughts

Overall, the translations are largely similar in approach. The Khokhar translation is a bit simpler, while the Bokhari translation is a tad more elegant. For a more easy landing into Urdu, we’d recommend Khokhar. For something a little more literary, Bokhari is probably the better bet. This is reflected in the Spellman Spectrum rating, which rates Khokhar’s translation at 34.5 (indicating an easier read for language learners) and Bokhari’s at 53.4 (indicating a read that jibes somewhat better with Urdu literary standards). But if one is more accessible to you—whether you have Khokhar in your local library or Bokhari is easier to find online—there’s not much lost in being “stuck” with one or the other!

Leave a Reply