This article has a companion article that provides additional context: Asturian Language: The Story of Bable and Its Features.

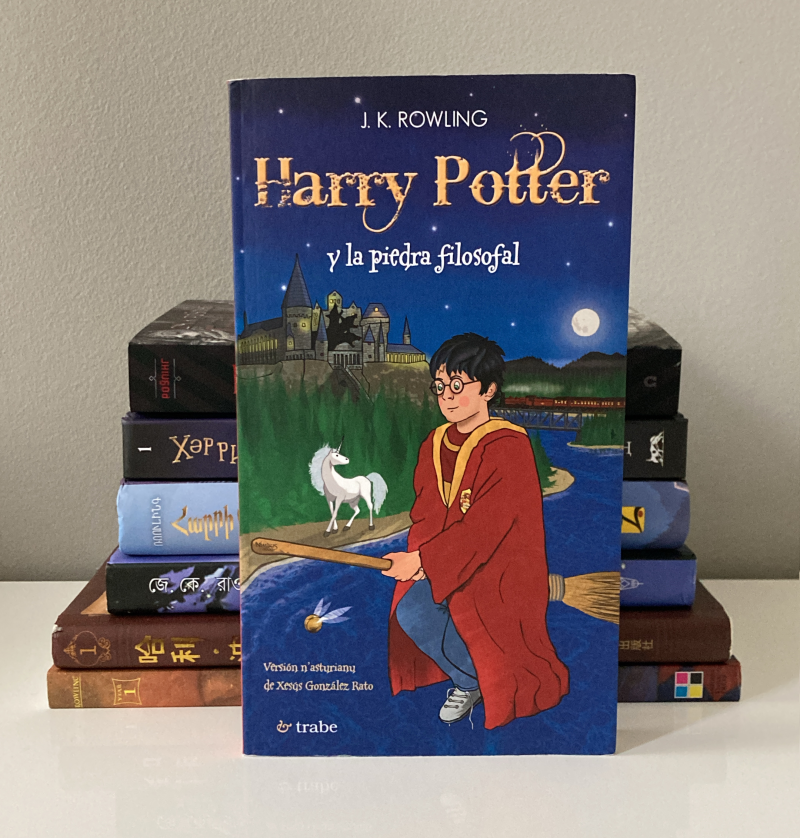

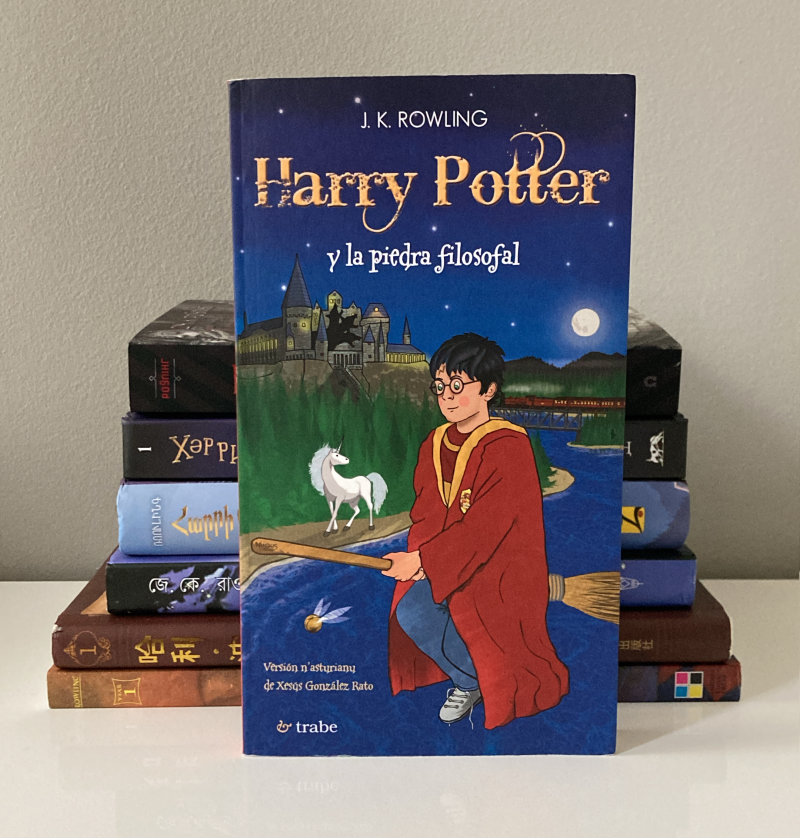

One of the most difficult translations of Harry Potter to access is the Asturian Harry Potter y la piedra filosofal (ISBN 84-8053-549-0 / 978-84-8053-549-6), whose name is identical to the Spanish title. With its unique font and cover art (by Samuel Castro González), the number of people seeking a copy may even exceed the 700 (!) copies ever printed. So we thought we’d offer readers a little taste of what’s inside the book.

Illustration

The cover art draws immediate attention to the fantastical magic within the book’s pages. In the foreground Harry rides prominently on a broom as a unicorn stares up at him from the edge of the Forbidden Forest. The full moon hanging in the background illuminates both the unicorn and the night sky around it. The cover’s hue darkens as your eyes venture upwards from the moon’s luminosity. At first glance, the pointy silhouette of Fluffy (or Peludín in Asturian) in the castle (enlarged ominously on the back cover) resembles three witches’ hats that echo our trio of Harry, Ron, and Hermione.

Set against the dark blue backdrop of a starry night sky, it’s the only Harry Potter cover that captures the first visual impression of Hogwarts that we get from the novel itself: “Perched atop a high mountain on the other side, its windows sparkling in the starry sky, was a vast castle with many turrets and towers.” (See below for the translation in both Asturian and Spanish.)

Asturian: Mangáu no cimero un monte altu nel otru llau, coles ventanes relluciendo en cielu estrelláu, había un castiellu escomanáu con abondes torres y torretes.

Spanish: En la punta de una alta montaña, al otro lado, con sus ventanas brillando bajo el cielo estrellado, había un impresionante castillo con muchas torres y torrecillas.

Although it was published in 2009—eight years after the Warner Bros. film premiered in cinemas—it bucks the iconic Scholastic font in favor of something more plain yet marvelous and fleeting like a shooting star. The binding of the book, meanwhile, stands in a stark red contrast to the blue front and back.

Language, translation, and content

The translation into Asturian was done by Xesús González Rato, a medic by profession but a seasoned translator on the side. He’s brought at least a dozen foreign language works into Asturian, at very little pay. For his translation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days, he received some 1,800 euros.

The title was almost translated as Harry Potter y el piedru filosofal to distinguish it from the Spanish title. (Those of us who have tried to track down copies of this book would have been very grateful for that title.) The word piedru is found in Asturian dictionaries as a synonym for piedra. But it’s not a well-known variant by Asturian speakers, so that title was nixed. An alternative title was floated (Harry Potter y l’elixir de la vida, “Harry Potter and the Elixir of Life”) but the idea to stray from the English title ultimately didn’t sit well.

So how does the story read in Asturian? As we love to do at Potter of Babble (or, in this post, Potter of Bable), let’s start with the very beginning and compare it with the Spanish translation:

English: Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. They were the last people you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious, because they just didn’t hold with such nonsense.

Asturian: El señor y la señora Dursley, del númberu cuatro del Camín de los Sanxuaninos, taben arguyosos de dicir que yeren dafechamente normales, gracies al cielu. Yeren les postreres persones qu’ún esperaría ver envueltes en coses rares o misterioses, porque nun podíen ver babayaes asemeyaes.

Spanish: El señor y la señora Dursley, que vivían en el número 4 de Privet Drive, estaban orgullosos de decir que eran muy normales, afortunadamente. Eran las últimas personas que se esperaría encontrar relacionadas con algo extraño o misterioso, porque no estaban para tales tonterías.

You can listen to this paragraph read aloud over at Carly and Harrison’s The Book That Lives project.

Already we can say a few things about the Asturian translation in comparison with the better known Spanish translation. We immediately notice linguistic differences, like the feminine plural -es (gracies, coses rares o misterioses, babayaes) and the masculine -u (númberu, cielu) and the neuter -o (cuatro), which are distinctive features mentioned in our earlier post about the Asturian language.

Another observation is in the difference (and similarity) in translation strategy. On the one hand, they take very different approaches to translating the phrase “thank you very much.” The Asturian text translates the phrase as gracies al cielu (“thank heavens”), an expression of relief that the Dursleys are normal people. (This is the same approach taken by the translators of the Catalan, Portuguese, and Occitan editions.) The Spanish text, by contrast, translates it as afortunadamente (“fortunately”), an expression that emphasizes how proud the Dursleys are to be normal.

The translation of “they just didn’t hold with such nonsense” is similar in both languages. The Asturian translation is porque nun podíen ver babayaes asemeyaes (“because they couldn’t come off as blabbermouths”), while the Spanish has porque no estaban para tales tonterías (“because they weren’t for such nonsense”). The Spanish translation conveys the original English phrase more literally, however, while the Asturian provides a little more colloquial pizzazz with its use of the slang word babayaes.

Overall, this seems to illustrate the approach that the Asturian translation takes. Like Spanish, it’s relatively faithful to the English original. But it’s much more colloquial than the Spanish, presumably to ensure the translation has a sufficient Asturian flavor.

Notably, the translation nativizes a surprising amount of the proper nouns in the novel for such a late translation. After the Harry Potter films made their mark in franchising, this became an uncommon feature in new translations. Here are a few select examples in the table below:

| English | Asturian | Derivation and meaning |

|---|---|---|

| knuts | kuenxus | From cuenxu (nut) |

| sickles | focetus | From focetu (sickle) |

| galleons | galeonis | From galeón (galleon) |

| golden snitch | raitana dorada | From raitana (robin) and dorada (golden) |

| bludger | porriador | From porriador (pounder) |

| quaffle | cuatriada | Name of the ball used in Asturian bowling (called bolos); so named because the ball is used to knock down pins in a square (cuadru). |

| Cleansweep Seven (the broomstick) | Espolvadora Siete | From espolvar (dust off) |

| Oliver Wood | Oliver Maderu | From maderu (log) |

| Fang | Canil | From canil (fang) |

| Fluffy | Peludín | From peludín (fluffy) |

| goblin | duende | From duende, a category of small humanoid creatures that often live one’s house and cause mischief (similar to the puck) |

| chocolate frogs | xaronques de chicolate | From xaronca (frog) and chicolate (chocolate) |

| Bertie Botts Every Flavor Beans | gominoles Bertie Bott de tolos tastos | From gominola (gummy), tol (all), and tastu (flavor) |

| You-Know-Who | El-Qu’Usté-Sabe / El-Que-Tu-Sabes | Literally, He-Whom-You-Know-Of. Usté is used when talking to a stranger or a superior. Tu is used with peers. |

| Bathilda Bagshot | Balbina Sacurrotu | From sacu (bag) and rotu (broken) |

| Emeric Switch | Eméritu Tornadures | From tornador (switch) |

| Newt Scamander | Lleontín Scavera | From sacavera (salamander); the word for newt is guardafoentes (literally, fountain guardian) and not a good personal name. The Asturian personal name Lleontín means “little lion.” |

| Leaky Cauldron | El Calderu Afuracáu | From calderu (cauldron) and afuracáu (holey; used to describe someone who spends carelessly, such as someone who runs a large tab) |

| Ollivander | Olivarines | May be invoking olivar, meaning “to pine for” something, perhaps a reference to the role of one’s personality in the type of wood used for your wand. |

| Quidditch through the Ages | Quidditch al traviés de los tiempos | From al traviés (across) and tiempos (time) |

| Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | Animales fantásticos y ú los atopar | From ú (where) and atopar (find) |

The most iconic proper nouns, of course, have remained the same: Gryffindor is still Gryffindor, Albus Dumbledore is still Albus Dumbledore, and Hogwarts is still Hogwarts.

According to González Rato, Philosopher’s Stone in Asturian was considered a success. He completed a translation for the second book, which was scheduled for publication in December 2013. It never was published, though, and no reason has been given, but the fact that it took two years to get the permissions to publish the first novel might lend a hint.

Hagrid in Asturian

So how do you represent a character like Hagrid in a language that’s small both geographically and in number of speakers? Luckily, Asturian has no shortage of dialectal variation! Hagrid is reimagined as a native of Ciañu, a small mining town along the Nalón river to the southeast of Asturia’s capital of Ovieda.

The accent in Ciañu is characterized especially by certain changes to the vowels, like the raising of “o” and “e” to “u” and “i” in certain instances. Take, for instance, how Hagrid says cuántos díes (“how many days”) and vos (“you guys”) in the following:

— ¿Cuántus díis vus quedin pa lis vacacionis? — entrugó Hagrid.

“How many days you got left until yer holidays?” Hagrid asked.

See also the following (and compare how he says moto, bones nueches, and señor):

— Voi devolve-y a Sirius la motu. Bonis nuechis, profesora McGonagall, profesor Dumbledore, siñor.

“I’ll be takin’ Sirius his bike back. G’night, Professor McGonagall — Professor Dumbledore, sir.”

Not only does Hagrid speak a real, non-standard Asturian accent, but the accent chosen by the translator is as clearly provincial to the Asturian reader as his accent is in English.

A Taste of Harry Potter in Asturian

Now let’s take a look at a specific scene in the novel, featuring some iconic moments and characters, and compare the translation in Asturian and Spanish:

| English (J.K. Rowling) | Asturian (González Rato) | Spanish (Rawson) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| The egg was lying on the table. There were deep cracks in it. Something was moving inside; a funny clicking noise was coming from it. | El güevu taba na mesa. Tenía delles regalles. Dientro movíase daqué y facía unos chasquíos estraños. | El huevo estaba sobre la mesa. Tenía grietas en las cáscara. Algo se movía en el interior y un curioso ruido salía de allí. | Compare Asturian güevu vs. Spanish huevo (egg), an iconic difference between the two languages. |

| They all drew their chairs up to the table and watched with bated breath. | Toos averaron les sielles a la mesa y aguardaron ensin respirar. | Todos acercaron las sillas a la mesa y esperaron, respirando con agitación. | |

| All at once there was a scraping noise and the egg split open. The baby dragon flopped onto the table. It wasn’t exactly pretty; Harry thought it looked like a crumpled, black umbrella. Its spiny wings were huge compare to its skinny jet body, it had a long snout with wide nostrils, the stubs of horns and bulging, orange eyes. | Hebo un ruíu y el güevu abrió. La cría de dragón dexóse cayer na mesa. Nuna yera precisamente guapu; Harry pensó qu’asemeyaba un paragües prietu arrugáu. Les sos ales espinoses yeren escomanaes comparaes col so esmirriáu cuerpu prietu, tenía un focicu llargu coles narines anches, esbozos de cuernos y güeyos saltones color naranxa. | De pronto se oyó un ruido y el huevo se abrió. La cría de dragón aleteó en la mesa. No era exactamente bonito. Harry pensó que parecía un paraguas negro arrugado. Sus alas puntiagudas eran enormes, comparadas con su cuerpo flacucho. Tenía un hocico largo con anchas fosas nasales, las puntas del os cuernos ya le salían y tenía los ojos anaranjados y saltones. | Two other iconic differences appear here: Asturian focicu vs. Spanish hocico (snout) and Asturian güeyos vs. Spanish ojos (eyes). |

| It sneezed. A couple of sparks flew out of its snout. | Espirrió. Saliéron-y delles chispes del focicu. | Estornudó. Volaron unas chispas. | Notice the Asturian text more accurately follows the English text, here and elsewhere in this scene. |

| “Isn’t he beautiful?” Hagrid murmured. He reached out a hand to stroke the dragon’s head. It snapped at his fingers, showing pointed fangs. | —¿Nun ye preciosu, ho? –marmulló Hagrid. Allargó una mano pa cariciar la cabeza del dragón. Esti taragañó-y los deos, amosando unos caniles puntiaos. | —¿No es precioso? —murmuró Hagrid. Alargó una mano para acariciar la cabeza del dragón. Este le dio un mordisco en los dedos, enseñando unos comillos puntiagudos. | The Asturian text adds “ho” to Hagrid’s comment for greater, colloquial effect. |

| “Bless him, look, he knows his mommy!” said Hagrid. | »¡Benditu sía, mirái, conoz a so ma! –dixo Hagrid. | —¡Bendito sea! Mirad, conoce a su mamá —dijo Hagrid. | |

| “Hagrid,” said Hermione, “how fast do Norwegian Ridgebacks grow exactly?” | —Hagrid –dixo Hermione–, ¿cómo medren de rápido los llombucrestaos noruegos, exautamente? | —Hagrid —dijo Hermione—. ¿Cuánto tardan en crecer los ridgebacks noruegos? | Asturian translates Ridgebacks as llombucrestaos while Spanish retains ridgebacks. |

| Hagrid was about to answer when the color suddenly drained from his face — he leapt to his feet and ran to the window. | Hagrid diba retrucar cuando de sópitu marchó-y tola color de la cara… Llevantó d’un saltu y corrió pa la ventana. | Hagrid iba a contestarle, cuando de golpe su rostro palideció. Se puso de pie de un salto y corrió hacia la ventana. | |

| “What’s the matter?” | —¿Qué pasa? | —¿Qué sucede? | |

| “Someone was lookin’ through the gap in the curtains — it’s a kid — he’s running back up ter the school.” | —Había daquién mirando pela regalla lis cortinis… Ye un rapaz… Vuelve corriendo pal colexu. | —Alguien estaba mirando por una rendija de la cortina… Era un chico… Va corriendo hacia el colegio. | Pronouns are one of the major differences between the languages. Here we see Asturian daquién vs. Spanish alguien (somebody). |

| Harry bolted to the door and looked out. Even at a distance there was no mistaking him. | Harry echó a correr pa la puerta y miró afuera. Inda a aquella distancia nun había dubia. | Harry fue hasta la puerta y miró. Incluso a distancia, era inconfundible: | |

| Malfoy had seen the dragon. | Malfoy viera’l dragón. | Malfoy había visto el dragón. |

If you enjoyed this article, check out its companion on the Asturian language to learn more and to find out what resources you can use to help you read your copy of Harry Potter in Asturian!

As always, happy exploring!

Leave a Reply