Home

-

Stay engaged and connect with the community! Join the email list, take part in Ask A Question, and connect on social media!

There are at least hundreds of people active online in discussing, collecting, and trading translations of Harry Potter. The total number of collectors worldwide probably numbers in the thousands.

One of the primary goals of Potter of Babble is to help foster this growing community and keep them engaged in active discussion! Here are four ways you can get more involved:

1. Join the Potter of Babble email list! – The list, meant to facilitate frequent email interaction via Google Groups, is moderated by Potter of Babble and includes occasional news on Harry Potter translation and updates about the website. It’s also a great resource for reaching out to the community with questions and requests, to let other collectors know if you have an extra copy of something, or simply to share the latest addition to your collection!

2. Use the Ask A Question feature – We’re testing out a public-facing feature that allows public discussion on Harry Potter translation, drawing from a larger pool of people who are casually visiting the website and may not be interested in committing to an email listserv. We’ll develop this into a more advanced feature if it turns out to be popular!

3. Connect on Instagram and Twitter – Instagram is an especially popular venue for connecting with Harry Potter collectors around the world!

4. Listen to the Dialogue Alley podcast and join their Patreon to request access to the Discord server – A great listen for your morning commute and a great way for instant communication with other collectors!

-

Harry Potter in Hebrew: how good is the translation?

On some level, Hebrew is an interesting choice for translation of the Harry Potter series. The 20th-century revival of the language, which was in minimal use for some two thousand years, was a bit on the controversial side. For centuries it had been a holy language, reserved for the Tanakh, for prayer, and for religious discussion, but not for everyday tasks. Early on, some of the Jews in the Holy Land who were eager to establish a Jewish state advocated Yiddish as the common language of Israel—Hebrew was simply too holy. Ultimately, Hebrew won out. And by the turn of the century, even books about wizards and witches (Harry Potter!) ended up published in the language.

Another reason why translation into Hebrew is interesting is because the ancient language’s literary culture is really very young. There isn’t a ton of history of the language being used to express complex imagery, and intertextuality is relatively restricted to the Bible and other well-known but extrascriptural religious texts. On top of that, for much of the 20th century the audience for Hebrew literature was dominated by non-native speakers who had picked up the language sometime after early childhood, and so the market for literature using intricate literary devices was limited.

Those circumstances did not leave much room for creativity. And, frankly, that’s reflected very typically in Hebrew-language fiction, in Hebrew-language music, in Hebrew-language poetry, and other forms of expression. Deep and complex ideas are expressed in the language, that’s for sure, but not in the most poetic of ways. This will change over time as generations of native Hebrew speakers continue to build a modern literary culture.

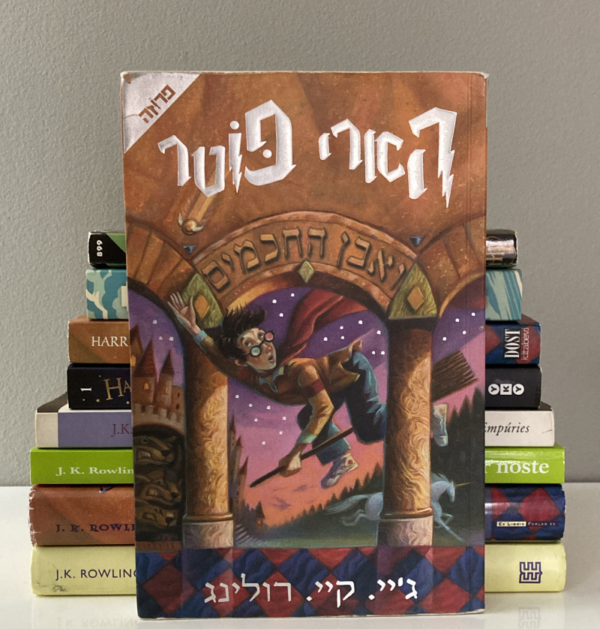

Simplicity in translation, especially for those new to the Hebrew alphabet

הארי פוטר ואבן החכמים, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in Hebrew. Translated by Gili Bar-Hillel in 2000. But Harry Potter ve-Even haHochmīm is very much effected by this situation. Not only was it translated in the nascence of modern Hebrew literature, it also seems to cater to non-native learners. One of the many, clear indications of this is the translation of “Remembrall”: kadōr hazikkarōn “memory ball.” It’s remarkably plain—almost uniquely plain among all the world’s translations—but the straightforward translation ensures that newcomers to Hebrew will not miss the reference.

Complicating matters for many readers is the Hebrew script. Not only do newcomers to the language almost invariably have to learn the alphabet from scratch, but vowels are not usually written, which can make it extra difficult to infer the meaning of neologisms.

Hebrew alphabet and phonetic values, including vowels (niqqud). The ancient script was invented before vowels had been conceptualized. If you think about it, vowels are simply tongue movements between consonants. Your tongue is moving, but it isn’t actually touching anything. It’s much easier to conceptualize consonants like “d” and “k,” because your tongue is touching a very specific spot. So those very tangible sounds were written down, but the movements between those sounds were not.

That’s a gross oversimplification of the situation. There are other factors that led to consonants being written before vowels, like the transition from logograms (like hieroglyphics) to consonants and the triconsonantal root system of Hebrew. But we don’t need to get into all the nitty-gritty just to say that vowels were invented later.

Needless to say, vowels were eventually invented and written down, but Hebrew, with its long tradition of writing without vowels, only uses them in specific situations. The phrase kadōr hazikkarōn, for example, is written <kdor hzikron>.

Drawing on Jewish traditions and literature

But all this does not stop Hebrew from getting creative in its translation of Harry Potter! While the book’s use of the Hebrew language is not particularly creative, it does draw ideas from its ancient religious literature.

One example is the translation of “hags” in Chapter 5 of Philosopher’s Stone. The Hebrew version translates it into liliōt, “Liliths.” Lilith refers to a sort of demonic figure primarily in post-biblical literature (see “Lilith” at Jewish Encyclopedia). Conceived at some point in Jewish literature as Adam’s first wife, Lilith takes on human form (but is often winged as angels and demons are often conceived) and has some level of antipathy towards human children since they are the progeny of Eve.

Spellman Spectrum: 66.5 (92.4%) On the Spellman Spectrum, the Hebrew translation receives a score of 66.5. Expect an enjoyable and approachable reading experience if you know some Hebrew and want to pick up a copy of this translation! Don’t expect poetry, but that makes it great for an intermediate student of Hebrew who wants to practice and enjoy this book to its fullest.

Have you read Harry Potter in Hebrew? Let us know what you think of the translation, and let us know your favorite parts.

-

Dumbledore’s favorite sweet (or drink?): sherbet lemons and lemon sherbets

Albus Dumbledore is an absolute treat. So full of wisdom, wit, serenity, and composure—and he has remarkable love and patience to boot. It’s impossible not to love the light-hearted fellow as much as you would your own grandfather, and even more so when you learn just how human he really is: his background story, especially with his sister Ariana and his brother Aberforth, is revealed to be tragic.

It’s in our very first encounter with Dumbledore that we get a taste of his personality. And that memorable moment when we learn his favorite treat is precisely when we learn just what kind of easy-going person he is:

[Professor McGonagall:] “I suppose he really has gone, Dumbledore?”

“It certainly seems so,” said Dumbledore. “We have much to be thankful for. Would you care for a lemon drop?”

“A what?”

“A lemon drop. They’re a kind of Muggle sweet I’m rather fond of.”

“No, thank you,” said Professor McGonagall coldly, as though she didn’t think this was the moment for lemon drops.”

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (US)Going through this translation in Turkish (Ülkü Tamer) one day, I was struck to find that Dumbledore’s favorite treat was translated into a beverage!

“Limon şerbeti. Muggle’ların bir çeşit tatlı içeceği. Hoşuma gidiyor.”

“Lemon sorbet. It’s a kind of Muggle soft drink. I enjoy it.”

Harry Potter ve Felsefe Taşı (Ülkü Tamer, Turkish)The confusion comes from the UK version of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, where lemon drop is called “sherbet lemon.” For those of us who read the American editions, we’re familiar with “sherbet lemon” as the password to Dumbledore’s office in Goblet of Fire (but “lemon drop” in Chamber of Secrets). As it turns out—and I did not know this until coming across this Turkish translation—Dumbledore’s password should be the same in the two books. But in GoF, the editors apparently didn’t catch that they had earlier translated “sherbet lemon” to “lemon drop.”

What’s sherbet? Most of the world thought it was ice cream…

What the British mean by sherbet lemons The reason “sherbet lemon” became “lemon drop” in the American version is simple: the candy called “sherbet lemon” in the UK is called “lemon drop” by Americans. And in the US, “sherbet” refers to a frozen juice (similar to sorbet).

In fact, the British use of “sherbet” in this manner is unique. The word sherbet comes from Turkish, which in turn comes from Arabic, sharbah, which actually means “beverage.” In the UK, a variant of the sweet Turkish drink at some point began appearing in a powdered form, and the word “sherbet” came to refer to this powder as well as candies that use that powder, such as the sherbet lemon.

Translators grappled with this particular translation, lacking the cultural knowledge of what exactly “sherbet lemon” means in British English. It’s not only Turkish that transformed the delectable into a drink.

In Luxembourgish, it’s a Spruddelkamel, which may just be carbonated water with lemon flavoring.

The Portuguese translation (by Isabel Fraga) makes it into lemonade, even explicitly saying “é uma bebida dos Muggles de eu gosto muito”—”it’s a Muggle drink that I’m really fond of.”

And according to @knockturnerik on the podcast Dialogue Alley, the ultra rare Gujarati translation also transformed the sherbet lemon into a lemonade.

In many (perhaps even most?) translations, it becomes a type of sorbet:

In Icelandic, it’s a Sítrónukrap, which seems to be a slightly more liquidy sorbet.

/frimg/1/6/92/1069290.jpg)

Icelandic Sítrónukrap. See recipe at mbl.is. In French, it’s an esquimau (literally, “eskimo”), which seems to be a type of popsicle.

In Albanian, it’s akullore me limon—just straight up ice cream. (Poor McGonagall that she doesn’t even know what ice cream is!)

A few translations come up with different sweets that belong to the local culture.

In Catalan, it’s a pica-pica de llimona, which seems to refer to a tapa-style dessert in Catalonia.

Finnish changes it to Sitruunatoffeeta, or lemon-flavored toffee.

Completely different is the Hebrew translation, which features the קרמבו (krembo), a very popular wintertime sweet in Israel featuring marshmallow fluff and a cookie, all covered in chocolate. Nothing to do with lemon!

A German Schaumkuss, similar to the Israeli Krembo. Popular in many European countries, there is no American equivalent. What is the password to Dumbledore’s office in translation?

On a different note, this made me curious whether translations were consistent in PS/SS and CoS between references to the sherbet lemon. Was the password to Dumbledore’s office in CoS the same as his favorite treat cited at the beginning of PS/SS?

The Turkish Chamber of Secrets did adopt “limon şerbeti.” It had a different translator from Philosopher’s Stone, but this may have just been a very literal translation of “sherbet lemon” in both cases. By contrast, the German translation has Dumbledore offering a candy “Zitronenbrausebonbon” to McGonagall, but the password to his office is “Scherbert Zitrone.” The Dutch translation clearly caught on to the connection, though: Dumbledore offers a “zuurtje” (hard candy), and the password to his office is “Zak met zuurtjes”—“Bag of hard candies.”

At this time, I only have a few translations of CoS in my possession, so I don’t have a huge sample to work from. I’m especially curious if languages that have different translators for PS/SS and CoS picked up on this intertextual reference, as happened in the Turkish translations!

If you have a copy of CoS in other languages, leave a comment telling us what you find out to be Dumbledore’s password!

6 Responses to “Dumbledore’s favorite sweet (or drink?): sherbet lemons and lemon sherbets”

-

[…] does not stop Hebrew from getting creative in its own way in its translation of Harry Potter! As mentioned in the previous post, the Hebrew version of Harry Potter replaces Dumbledore’s preference for sherbet lemons with […]

-

[…] interested in many of our other articles on topics like Harry Potter in Hebrew, Dumbledore’s favorite sweets, Harry Potter in a made-up language, and HP Japanese book art. Potter of Babble is also looking for […]

-

[…] translated as kaṛahee, a flat-bottom style of wok specific to South Asia. Even Dumbledore’s favorite sweet is transformed into a sekanjabin, a refreshing honey-vinegar drink that’s also Persian in […]

-

[…] about just how much food is in the Harry Potter books? There’s a ton, from baked potatoes to lemon sherbets to Fizzing Whizzbees™. It is an important literary device, used to define settings and build […]

-

[…] This article is a PB Bite summary of the main article, Dᴜᴍʙʟᴇᴅᴏʀᴇ’s ꜰᴀᴠᴏʀɪᴛᴇ sᴡᴇᴇᴛ (ᴏʀ ᴅʀɪɴᴋ?): sʜᴇ…. […]

-

[…] One of our readers, Chen, reached out recently with questions about the translation of sherbet lemon (addressed in a previous post). […]

-

-

The Spellman Spectrum: rating Harry Potter translations on a scale of literal (source-oriented) to gist (target-oriented) translation

Translations are not mere vessels for a story, and neither are translators their captains. Translators are creators in their own right, effectively composing a brand new, living text that merely reflects the ideas put forth by the original author. (Klaus Schubert, an expert in technical translation, makes this argument even for the translation of the driest, most technical documents.)

As a visual parallel, I think of the innumerable interpretations of the Last Supper. Each painting is a different experience, and some paintings speak to us more than others.

The Last Supper by Jacopo Tintoretto, Italian Mannerist style, c. 1592–94.

The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, Italian Renaissance style, c. 1495–98.

The Last Supper by Vicente Juan Masip, Spanish Renaissance style, 16th century.

The Last Supper, Carl Broch, Realist style, 19th century. Or simply consider cover art: does Mary GrandPre’s interpretation of Harry Potter offer the same experience as Adrian Macho’s? How about Dan Schlesinger’s cover and book art?

For those of us who enjoy the artistry of translation, Harry Potter has a wide range of potential for translators’ expression. That’s why I’m introducing the Spellman Spectrum, which rates translations on a scale from literal (or source-oriented) translation to gist (target-oriented) translation.

The aim of the scale is to communicate the level of creativity and originality of a translation. A high score indicates that the translator has created a new experience for the reader. If you read Harry Potter in English and then reread it in a language with a high score, expect to enter a very different world from the one you knew in English! A low score indicates the translator’s loyalty to the original tale, meaning the translation is excellent for language learners who are still getting a grip on grammar, vocabulary, and idiomatic expression.

For comparison, the French translation by currently has a score of 89.7, while the Spanish translation has a score of 22.0. Reading Harry Potter in French is quite a joy, while reading it in Spanish is great language practice! In the middle falls the German translation, whose score of 58.2 reflects a balance between enjoyment and language practice.

How this model for comparing translations works…

The Spectrum is a work in progress. It will change over time through trial and error and as additional data is gathered. It is not scientific: subjective, quantitative models to compare translations do not exist, and most attempts toward developing scientific models are qualitative. But that’s nice, on the one hand, because that means the model we use can be tailored to fit the world of Harry Potter!

The model, in its basic conception, works like this:

Dozens of variables are compared across translations. Those variables include a range of samples, from names of people and magical objects to the use of sentence-level pragmatic devices. Each variable is assigned a numeric rating:

1: a literal translation

2: a translation that deviates slightly from the original English

3: a gist (target-oriented) translation; a reinterpretation that deviates significantly from the original English

The variables are weighted according to how complex the translation. Here are some of the general guidelines used to decide on variable weight:

- Names are very easy to alter, and receive the lowest weight.

- Sentence-level translations carry moderate weight when the English-language sentence includes a complex idiomatic structure.

- Culture-specific translations also carry moderate weight, but are rated with the translator’s application of the skopos principle in mind. (That is, keeping in mind whether the translator is attempting to portray a foreign wizarding world situated in Britain or a native wizarding world familiar to the country of the language.)

- Translations of idiomatic expressions (such as “thank you very much“) carry a moderate-to-high weight.

- The translation of language-based literary devices, such as puns, poems, play-on-words, carry heavy weight.

In some rare cases, a variable may receive extra weight in one language. This happens when a specific translator does something especially innovative, such as making an unexpected and unprompted connection to the target culture or creating connections within the story that were not present in the English source text.

Finally, because this calculation effectively restricts the range from 33%-100%, with the vast majority of translations following somewhere between 40%-70%, the scale applies an algorithm that stretches the median range so that it more broadly fills out the range of 1-100. Percentages on the extremities, 33-40% and 70-100%, have reduced ranges on the scale. This algorithm helps bring out the broad range in translation strategies applied in each translation so that the differences are easier to see.

Again, this non-scientific scale is a work in progress and I intend to fine tune it over time as I learn more. So be sure and check back every so often to see how the scores change!

-

“The Dursleys are perfectly normal, thank you very much!”: Idioms, immediately

Short on time? Get the bite-size summary here.

“Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.”

What better way to open Potter of Babble than with the opening sentence of the Harry Potter series?

One of my favorite translations of this sentence comes from the Scots translation, which English speakers can read and understand: “Mr and Mrs Dursley, of nummer fower, Privet Loan, were prood tae say that they were gey normal, thank ye verra much.”

It’s so conversational and colloquial! You can just imagine someone sitting next to you and telling you about the Dursleys, and that feeling of familiarity with the storyteller is exactly what you should feel at the beginning of any good, pleasant story.

The original English-language narration strikes a similar tone, and it’s most evident with the phrase “thank you very much.” You may have never thought about it before, but the use of “thank you” in this context is pretty idiomatic and largely unique to English. When the Dursleys say “thank you very much,” they’re not actually thanking anyone for wondering if they’re normal. If anything, they’re offended! They’re saying “thank you very much” with their chins raised and their noses high in the air, showing their polite indignation that anybody would even suggest that they could be anything other than normal. And in fact, the use of “thank you very much” here serves as a very eloquent tool for the storyteller: that the Dursleys would respond “thank you very much” only proves how proud they really are.

So how do other translations deal with this very English-specific expression? Below are six—yes, six!—different strategies translators around the world have used to confront this challenging sentence.

Translator strategy #1: Translate it literally

Because this use of “thank you very much” is so specific to English, only a handful of languages attempt to translate it literally—like the closely related language Scots, as we saw above. Of course, it works with Scots because Scots is mutually intelligible with English and shares a significant overlap of social norms.

Click on the drop down list to see the translations that use this strategy.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #1 (Click for drop-down list)

Esᴘᴇʀᴀɴᴛᴏ: Gesinjoroj Dursli ĉe numero kvar, Ligustra Vojo, fieris diri, ke ili estas “perfekte normalaj, multan dankon.”

Rᴜssɪᴀɴ (Maria Spivak): Мистер и миссис Дурслей, из дома Но. 4 по Бирючинной улице, гордились тем, что они, спасибо преогромное, люди абсолютно нормальные.

Sᴄᴏᴛs: Mr and Mrs Dursley, of nummer fower, Privet Loan, were prood tae say that they were gey normal, thank ye verra much.

Wᴇʟsʜ: Broliai Mr a Mrs Dursley, rhif pedwar Privet Drive, eu bod nhw’n deulu cwbl normal, diolch yn fawr iawn ichi.

One interesting observation here is that the Esperanto translation uses this strategy. In a future post, I’ll address how the Esperanto translation frequently uses very literal translations and what this might mean for the Esperanto community in terms of language vitality.

Translator strategy #2: Reinterpret “thank you very much”

The largest portion of the translations use “thank you very much” as an expression of relief instead of an expression of indignation. “Thank God we are perfectly normal!” This is a very literal translation that is deceptively similar to the “thank you very much” in the English source text, but it does not express the contempt intended in “thank you very much.”

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #2 (Click for drop-down list)

Aᴢᴇʀʙᴀɪᴊᴀɴɪ: Mister və missis Durslilər Rivet Drayv küçəsində 4 nömrəli evdə yaşayır və həmişə fəxrlə bildirirdilər ki, onlar, şükür Allaha, tamamilə normal insanlardır.

Bᴀsǫᴜᴇ: Dursley jaun-andreek, Privet Driveko 4.ekoek, harro esaten zuten beraiek erabat normalak zirela, zorionez!

Bʀᴇᴛᴏɴ: An aotrog hag an itron Durlsey, a oa o chom en niverenn 4, Privet Drive, ha lorc’h a veze enne o lavarout e oant tud ordinal penn-kil-ha-troad, ho trugarekaat.

Cᴀᴛᴀʟᴀɴ: El senyor i la senyora Dursley, del carrer Privet número quatre, estaven molt orgullosos de poder dir que eren gent perfectamente normal, gràcies a Déu.

Cʀᴏᴀᴛɪᴀɴ (Zlatko Crnković): Gospodin i gospođa Dursley, iz Kalinina prilaza broj četiri, bili su ponosni što su normalni ljudi da ne mogu biti normalniji i još bi vam zahvalili na komplimentu ako biste im to rekli.

Fᴀʀᴏᴇsᴇ: Hjúnini Dursley, maðurin og konan, sum búðu í Privet gøtu nummar 4, vóru errin um at kunna siga, at tey vóru púra vanlig fólk, og takk fyri tað.

Gʀᴇᴇᴋ, Aɴᴄɪᴇɴᴛ: Δούρσλειος καὶ ἡ γυνὴ ἐνῷκουν τῇ τετάρτῃ οἰκίᾳ τῇ τῆς τῶν μυρσίνων ὁδοῦ. ἐσεμνύνοντο δέ περὶ ἑαυτοὺς ὡς οὐδὲν διαφέρουσι τῶν ἄλλων ἀνθρώπων, τούτου δ’ἓνεκα χάριν πολλὴν ᾔδεσαν.

Oᴄᴄɪᴛᴀɴ: Sénher e Dauna Dursley qui demoravan au 4, Privet Drive, qu’èran gloriós de’s díser perfèitament normaus, Diu mercés.

Iᴛᴀʟɪᴀɴ: Il signore e la signora Dursley, di Privet Drive numero 4, erano orgogliosi di affermare di essere perfettamente normali, e grazie tante.

Lɪᴛʜᴜᴀɴɪᴀɴ: Ponia ir ponas Dursliai, gyvenantys ketvirtame Ligustrų gatvės name, išdidžiai sakydavo, jog jie, ačiū Dievui, normalių normaliausi žmonės.

Pᴏʟɪsʜ: Państwo Dursleyowie spod numeru czwartego przy Privet Drive mogli z dumą twierdzić, że są całkowicie normalni, chwała Bogu.

Pᴏʀᴛᴜɢᴜᴇsᴇ (Isabel Fraga): Mr. e Mrs. Dursley, que vivem no número quatro de Privet Drive, sempre afirmaram, para quem os quisesse ouvir, ser o mais normale que é possível ser-se, graças a Deus.

Rᴏᴍᴀɴɪᴀɴ (Ioana Iepureanu): Domnul şi doamna Dursley, de pe Aleea Boschetelor, numărul 4, erau foarte mândri că erau complet normali, slavă Domnului!

Rᴏᴍᴀɴɪᴀɴ (Florin Bacin): Domnul şi doamna Dursley, din Aleea Privet numărul patru, erau mândri să poată spune că ei, slavă Domnului, sunt absolut normali.

Rᴜssɪᴀɴ (Igor W. Oranskij): Мистер и миссис Дурсль проживали в доме номер четыре по Тисовой улице и всегда с гордостью заявляли, что они, слава богу, абсолютно нормальные люди.

Tᴜʀᴋɪsʜ (Mustafa Bayındır): Privet Sokaği, Dört Numara’daki Bay ve Bayan Dursley, sağ olsunlar, tamamen normal olduklarını söylemekten gurur duyarlardı.

Tᴜʀᴋɪsʜ (Ülkü Tamer): Privet Drive dört numarada outran Mr ve Mrs Dursley, son derece normal olduklarını söylemekten gurur duyarlardı, sağ olun efendim.

Uᴋʀᴀɪɴɪᴀɴ: Містер і місіс Дурслі, що жили в будинку номер чотири на вуличці Прівіт-драйв, пишалися тим, що були, слава Богу, абсолютно нормальні.

Uᴢʙᴇᴋ (Shokir Dolimov): «Odamovilar» xiyobonidagi 4-uy sohiblari mister va missis Dursllar: «Xudoga beadad shukurlar bo’lsinki, xonadonimizdagi hayot tinch va bir maromda kechmoqda», — deya maqtana olishlari bilan g’ururlanishadi.

If you read any of these languages, you’ll notice that the Dursleys come off very differently in this sentence than in the English sentence. Rather than rigid and uptight, you’re left with an image of a couple that is primarily self-conscious and perhaps a little bit judgmental.

Translator strategy #3: Replace “thank you very much” by expressing emphasis instead

Another popular strategy among translators is to recast the sentence with one that drives home the point that the Dursleys are proud to be normal. An English-language example of such replacement might be something like: “The Dursleys were darn proud to say they’re perfectly normal!”

This is a rather clever workaround that identifies the purpose of “thank you very much” in the English source text and attempts to reproduce its effect natively in the target language.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #3 (Click for drop-down list)

Fɪɴɴɪsʜ: Likusteritie nelosen herra ja rouva Dursley sanoivat oikein ylpeinä, että he olivat avian tavallisia totta tosiaan.

Fᴀʀsɪ/Pᴇʀsɪᴀɴ (Saeed Kobraiai): آقا و خانم دورسلی ساکن خانهی شمارهی چهار خیابان پریوت درایو بودند. خانوادهی آنها بسیار معمولی و عادی بود و آنها از این بابت بسیار راضی و خشنود بودند.

Gᴇʀᴍᴀɴ: Mr. und Mrs. Dursley im Ligusterweg Nummer 4 waren stolz darauf, ganz und gar normal zu sein, sehr stolz sogar.

Gʀᴇᴇᴋ, Mᴏᴅᴇʀɴ: Ο κύριος κι η κυρία Ντάρσλι, που έμεναν στον αριθμό 4 της οδού Πριβέτ, έλεγαν συχνά, και πάντα με υπερηφάνεια, πως ήταν απόλυτα φυσιολογικοί άνθρωποι, τίποτα περισσότερο ή λιγότερο.

Hᴀᴡᴀɪɪᴀɴ: Ua ha’aheo ‘o Mr Iāua ‘o Mrs Dursley o Helu ‘Ehā, Ala Pilikino, i ka ha’i aku he po’e ma’amau nō Iāua, mahalo nui loa.

Iᴄᴇʟᴀɴᴅɪᴄ: Dursleyhjónin á Runnaflöt númer fjögur hreyktu sér gjarnan af því að vera sérdeilis og algerlega eðlilegt fólk.

Iʀɪsʜ: Bhí cónaí ar mhuintir Dursley in uimhir a ceathair Privet Drive, agus é le maíomh acu go raibh said an-normálta go deo, agus iad breá sásta de.

Sᴘᴀɴɪsʜ: El señor y la señora Dursley, que vivían en el número 4 de Privet Drive, estaban orgullosos de decir que eran muy normales, afortunadamente.

Yɪᴅᴅɪsʜ: מ״ר און מר״ס דורזלי, פון דער ליגוסטער־גאַס נומער פיר, האָבן שטאָלצירט מיט דעם, וואָס זיי זענער געווען אין גאַנצן נאָר־מאַל – ווי עס באַדאַרף דאָך צו זײַן

Norwegian uses a mixed strategy, translating “thank you” directly but also adding an adverb for emphasis: “Herr og fru Dumling i Hekkveien 4 var heldigvis fullstendig normale, takk.”

Translator strategy #4: Reinterpret what the Dursleys mean by “normal”

In a few translations, the Dursleys’ “thank you” seems to come in response to a question about their happiness and well-being. “How are you doing today, Mr. and Mrs. Dursley?” “Quite normal today, thank you!” The effect of this reinterpretation suggests that the Dursleys are putting on a façade. They want their well-to-do neighbors to think they’re doing fine, but behind closed doors they’re anxious about what problems the Potters will bring them.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #4 (Click for drop-down list)

Bʀᴀᴢɪʟɪᴀɴ Pᴏʀᴛᴜɢᴜᴇsᴇ: O Sr. e a Sra. Dursley, da rua ados Alfeneiros, no 4, se orgulhavam de dizer que eram perfeitamente normais, muito bem, obrigado.

Cᴢᴇᴄʜ: Pan a paní Dursleyovi z domu číslo čtyři v Zobí ulici vždycky hrdě prohlašovali, že jsou naprosto normální, ano, děkujeme za optání.

Gᴀʟɪᴄɪᴀɴ: O señor e a señora Dursley, do número catro de Privet Drive, gabábanse de ser normais de todo, moitas gracias.

Hᴇʙʀᴇᴡ: אדון וגברת דרסלי, דיירי דרך פריווט מספר ארבע, ידעו לדוות בגאווה שהם נורמליים — ותודה ששאלתם.

Jᴀᴘᴀɴᴇsᴇ: プリベット通り四番地の住人ダーズリー夫妻は、「おかげさまで、私どもはどこからみてもまともな人間です」と言うのが自慢だった

Sʟᴏᴠᴀᴋ: Pán a pani Dursleyovci z Privátnej cesty číslo 4 s potešením o sebe tvrdili, že sú úplne normálni, no d’akujem pekne.

Only a few translations use this strategy. It’s unclear whether it’s an attempt to salvage the phrase “thank you very much” or if they translator misinterpreted the intended meaning of both “normal” and “thank you very much.” It might depend from translator to translator as well.

Translator strategy #5: Remove the phrase entirely.

Some translators identified that “thank you very much” is completely unnecessary in the sentence, and it can be cut if it causes them trouble. Cutting the phrase sidesteps the problem altogether and provides an easy way out for the translator. But the removal does change the tone of the narration—away from one that offers the reader a vantage point from Mr. Dursley’s perspective and towards a more omniscient one.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #5 (Click for drop-down list)

Bᴜʀᴍᴇsᴇ (Myanmar; Kaung Myat Loon Taw): ပရီဗက်ဒရိက်လမ်း အိမ်အမှတ် (၄) တွင် နေထိုင် ကြသော မစစတာနင့် မစစဒါစခလတို့မာှ သာမန်လူများ ဖြစ်ရခြင်း အတွက် သူတို့ကိုယ်သူတို့ ဂုဏ်ယူတြသည်။

Dᴀɴɪsʜ: Hr. og fru Dursley fra Ligustervænget nummer fire var Ganske stolte over, at de var helt og aldeles normale.

Gʀᴇᴇɴʟᴀɴᴅɪᴄ: Aappariit Dursleykkut Ligustervænget normu 4-meersut tulluusimaarutigaat inuttut nalinginnaalluinnartuunertik.

Hɪɴᴅɪ: प्रिवित ड्राइव के मकान नंबर चार में रहने वाले मिस्टर और मिसेज़ डर्स्ली गर्व से कहते थे हम तो पूरी तरह सामान्य लोग हैं |

Hᴜɴɢᴀʀɪᴀɴ: A Privet Drive 4. szám alatt lakó Dursley úr és neje büszkén állíthatták, hogy köszönik szépen, ők tökéletesen normálisak.

Lᴜxᴇᴍʙᴏᴜʀɢɪsʜ: De Mr an d’Mrs Dursley aus der Kellechholzstroos Nummer véier waren houfreg drop, soen ze kënnen, dass si ganz normal waren.

Mᴀʀᴀᴛʜɪ: प्रिव्हिट ड्राइव्हच्या चार नंबरच्या घरात राहणारे मिस्टर आणि मिसेस डर्स्ली मोठ्या ताठ्यानं सांगायचे की, आम्ही तर बाबा अगदी साधीसरळ माणसं आहोत.

Sᴡᴇᴅɪsʜ: Mr och Mrs Dursley i nummer fyra på Privet Drive var med rätta stolta över att kunna säga att de var helt normala.

Tɪɢʀɪɴʏᴀ (Ahadu Desta’alem): እንዳ ዳርስል፡ ኣብ ጐደና ሓጹራ – ቍጹረ ገዛ ኣርባዕተ ዝቐመጡ ደሓን ዝመነባብሮኦም ስድራቤት’ዮም።

The Dutch and Frisian translations take a unique approach that removes the phrase, but replaces it effectively by disconnecting the clause (“proud to say they were perfectly normal”) from the first sentence and attaching it to the second. This lends focus to their pride in being normal, much in the same way as strategy #3 does. The Arabic translator took a similar approach as well.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #5b (Click for drop-down list)

Aʀᴀʙɪᴄ: تفجر أسرة (درسلى) التي تقيم في المنزل رقم أربعة بشارع (بريفت درايف) بأنها أسرة طبيعية تمامًا..وهم كذلك فعلاً، لم يكن أحد ليتصور أن تتورط هذه الأسرة في أي أمور غريبة أو غامضة.

Dᴜᴛᴄʜ: In de Ligusterlaan, op nummer 4, woonden meneer en mevrouw Duffeling. Ze waren er trots op dat ze doodnormaal waren en als er ooit mensen waren geweest van wie je zou denken dat ze nooit bij iets vreemds of geheimzinnigs betrokken zouden raken waren zij het wel, want voor dat soort onzin hadden ze geen tijd.

Fʀɪsɪᴀɴ: Yn ‘e Ligusterleane, op nûmer 4, wennen Mûzema en de frou. Se wienen der grutsk op dat se hiel gewoan wienen en as der oait minsken west ha, dêrst fan tinke soest dat se noait by wat heimsinnichs of nuvers belutsen reitsje soenen, wiewol, want datsoarte flauwekul hienen se net oan tiid.

Translator strategy #6: Alternative expressions of indignation

One less common strategy, which I personally prefer, is to replace the “thank you very much” clause with a more native expression of indignation. This ultimately preserves the reader’s impression of the Dursleys as rigid and uptight, keeps the perspective of the narrative in the vantage point of Mr. Dursley, and overall provides a similar experience to the original English sentence.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #6 (Click for drop-down list)

Bᴏsɴɪᴀɴ: Gospodin i gospođa Dursley s broja četiri, Privet Drive, ceste biser-drveta, bili su ponosni što za sebe mogu reći da su savršeno normalni, ako bi se ko i usudio da upita.

Lᴀᴛɪɴ: Dominus et Domina Dursley, qui vivebant in aedibus Gestationis Ligustrorum numero quattuor signatis, non sine superbia dicebant se ratione ordinaria vivendi uti neque se paenitere illius rationis.

Mᴀᴏʀɪ: Whakahī ana a Mita rāua ko Miha Tūhiri, nō te kāinga tuawhā i te Ara o Piriweti, ki te kī he tino māori noa iho nei rāua – kia mōhio mai koe.

So for me, of the dozens of translations listed in this post, only the Bosnian, Latin, and Maori translations truly capture that first sentence in Harry Potter.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that the Thai translation also uses an alternative expression, but one that expresses desperation rather than indignation: นายและนางเดอร์สลีย์เจ้าของบ้านเลขที่สี่ ซอยพรีเว็ต ภาคภูมิใจนักที่จะบอกว่าพวกเขาเป็นคนปกติธรรมดาที่สุด เชื่อเขาเลย! No really! We are normal! We swear! Unlike the other translations of this strategy, however, it alters the reader’s image of the Dursleys much in the same way as strategy #2 above.

So, for me, of the dozens of translations listed in this post, only the Bosnian, Latin, and Maori translations truly capture that first sentence in Harry Potter as the story was originally written. What’s your favorite translation?

This was a little preview for you of how interesting the translation of Harry Potter can be! Leave a comment or a message and let me know what you thought. What did you like and what would you like to see more of in future posts?

-

Idioms, immediately: The Dursleys are perfectly normal, thank you very much!

“Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.”

What better way to open Potter of Babble than with the opening sentence of the Harry Potter series?

One of my favorite translations of this sentence comes from the Scots translation, which English speakers can read and understand: “Mr and Mrs Dursley, of nummer fower, Privet Loan, were prood tae say that they were gey normal, thank ye verra much.”

It’s so conversational and colloquial! You can just imagine someone sitting next to you and telling you about the Dursleys, and that feeling of familiarity with the storyteller is exactly what you should feel at the beginning of any good, pleasant story.

The original English-language narration strikes a similar tone, and it’s most evident with the phrase “thank you very much.” You may have never thought about it before, but the use of “thank you” in this context is pretty idiomatic and largely unique to English. When the Dursleys say “thank you very much,” they’re not actually thanking anyone for wondering if they’re normal. If anything, they’re offended! They’re saying “thank you very much” with their chins raised and their noses high in the air, showing their polite indignation that anybody would even suggest that they could be anything other than normal. And in fact, the use of “thank you very much” here serves as a very eloquent tool for the storyteller: that the Dursleys would respond “thank you very much” only proves how proud they really are.

So how do other translations deal with this very English-specific expression? Below are six—yes, six!—different strategies translators around the world have used to confront this challenging sentence.

Translator strategy #1: Translate it literally

Because this use of “thank you very much” is so specific to English, only a handful of languages attempt to translate it literally—like the closely related language Scots, as we saw above. Of course, it works with Scots because Scots is mutually intelligible with English and shares a significant overlap of social norms.

Click on the drop down list to see the translations that use this strategy.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #1 (Click for drop-down list)

Esᴘᴇʀᴀɴᴛᴏ: Gesinjoroj Dursli ĉe numero kvar, Ligustra Vojo, fieris diri, ke ili estas “perfekte normalaj, multan dankon.”

Rᴜssɪᴀɴ (Maria Spivak): Мистер и миссис Дурслей, из дома Но. 4 по Бирючинной улице, гордились тем, что они, спасибо преогромное, люди абсолютно нормальные.

Sᴄᴏᴛs: Mr and Mrs Dursley, of nummer fower, Privet Loan, were prood tae say that they were gey normal, thank ye verra much.

Wᴇʟsʜ: Broliai Mr a Mrs Dursley, rhif pedwar Privet Drive, eu bod nhw’n deulu cwbl normal, diolch yn fawr iawn ichi.

One interesting observation here is that the Esperanto translation uses this strategy. In a future post, I’ll address how the Esperanto translation frequently uses very literal translations and what this might mean for the Esperanto community in terms of language vitality.

Translator strategy #2: Reinterpret “thank you very much”

The largest portion of the translations use “thank you very much” as an expression of relief instead of an expression of indignation. “Thank God we are perfectly normal!” This is a very literal translation that is deceptively similar to the “thank you very much” in the English source text, but it does not express the contempt intended in “thank you very much.”

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #2 (Click for drop-down list)

Aᴢᴇʀʙᴀɪᴊᴀɴɪ: Mister və missis Durslilər Rivet Drayv küçəsində 4 nömrəli evdə yaşayır və həmişə fəxrlə bildirirdilər ki, onlar, şükür Allaha, tamamilə normal insanlardır.

Bᴀsǫᴜᴇ: Dursley jaun-andreek, Privet Driveko 4.ekoek, harro esaten zuten beraiek erabat normalak zirela, zorionez!

Bʀᴇᴛᴏɴ: An aotrog hag an itron Durlsey, a oa o chom en niverenn 4, Privet Drive, ha lorc’h a veze enne o lavarout e oant tud ordinal penn-kil-ha-troad, ho trugarekaat.

Cᴀᴛᴀʟᴀɴ: El senyor i la senyora Dursley, del carrer Privet número quatre, estaven molt orgullosos de poder dir que eren gent perfectamente normal, gràcies a Déu.

Fᴀʀᴏᴇsᴇ: Hjúnini Dursley, maðurin og konan, sum búðu í Privet gøtu nummar 4, vóru errin um at kunna siga, at tey vóru púra vanlig fólk, og takk fyri tað.

Gʀᴇᴇᴋ, Aɴᴄɪᴇɴᴛ: Δούρσλειος καὶ ἡ γυνὴ ἐνῷκουν τῇ τετάρτῃ οἰκίᾳ τῇ τῆς τῶν μυρσίνων ὁδοῦ. ἐσεμνύνοντο δέ περὶ ἑαυτοὺς ὡς οὐδὲν διαφέρουσι τῶν ἄλλων ἀνθρώπων, τούτου δ’ἓνεκα χάριν πολλὴν ᾔδεσαν.

Oᴄᴄɪᴛᴀɴ: Sénher e Dauna Dursley qui demoravan au 4, Privet Drive, qu’èran gloriós de’s díser perfèitament normaus, Diu mercés.

Iᴛᴀʟɪᴀɴ: Il signore e la signora Dursley, di Privet Drive numero 4, erano orgogliosi di affermare di essere perfettamente normali, e grazie tante.

Lɪᴛʜᴜᴀɴɪᴀɴ: Ponia ir ponas Dursliai, gyvenantys ketvirtame Ligustrų gatvės name, išdidžiai sakydavo, jog jie, ačiū Dievui, normalių normaliausi žmonės.

Pᴏʟɪsʜ: Państwo Dursleyowie spod numeru czwartego przy Privet Drive mogli z dumą twierdzić, że są całkowicie normalni, chwała Bogu.

Pᴏʀᴛᴜɢᴜᴇsᴇ (Isabel Fraga): Mr. e Mrs. Dursley, que vivem no número quatro de Privet Drive, sempre afirmaram, para quem os quisesse ouvir, ser o mais normale que é possível ser-se, graças a Deus.

Rᴏᴍᴀɴɪᴀɴ (Ioana Iepureanu): Domnul şi doamna Dursley, de pe Aleea Boschetelor, numărul 4, erau foarte mândri că erau complet normali, slavă Domnului!

Rᴏᴍᴀɴɪᴀɴ (Florin Bacin): Domnul şi doamna Dursley, din Aleea Privet numărul patru, erau mândri să poată spune că ei, slavă Domnului, sunt absolut normali.

Rᴜssɪᴀɴ (Igor W. Oranskij): Мистер и миссис Дурсль проживали в доме номер четыре по Тисовой улице и всегда с гордостью заявляли, что они, слава богу, абсолютно нормальные люди.

Tᴜʀᴋɪsʜ (Mustafa Bayındır): Privet Sokaği, Dört Numara’daki Bay ve Bayan Dursley, sağ olsunlar, tamamen normal olduklarını söylemekten gurur duyarlardı.

Tᴜʀᴋɪsʜ (Ülkü Tamer): Privet Drive dört numarada outran Mr ve Mrs Dursley, son derece normal olduklarını söylemekten gurur duyarlardı, sağ olun efendim.

Uᴋʀᴀɪɴɪᴀɴ: Містер і місіс Дурслі, що жили в будинку номер чотири на вуличці Прівіт-драйв, пишалися тим, що були, слава Богу, абсолютно нормальні.

Uᴢʙᴇᴋ (Shokir Dolimov): «Odamovilar» xiyobonidagi 4-uy sohiblari mister va missis Dursllar: «Xudoga beadad shukurlar bo’lsinki, xonadonimizdagi hayot tinch va bir maromda kechmoqda», — deya maqtana olishlari bilan g’ururlanishadi.

If you read any of these languages, you’ll notice that the Dursleys come off very differently in this sentence than in the English sentence. Rather than rigid and uptight, you’re left with an image of a couple that is primarily self-conscious and perhaps a little bit judgmental.

Translator strategy #3: Replace “thank you very much” with emphasis

Another popular strategy among translators is to recast the sentence with one that drives home the point that the Dursleys are proud to be normal. An English-language example of such replacement might be something like: “The Dursleys were darn proud to say they’re perfectly normal!”

This is a rather clever workaround that identifies the purpose of “thank you very much” in the English source text and attempts to reproduce its effect natively in the target language.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #3 (Click for drop-down list)

Fɪɴɴɪsʜ: Likusteritie nelosen herra ja rouva Dursley sanoivat oikein ylpeinä, että he olivat avian tavallisia totta tosiaan.

Fᴀʀsɪ/Pᴇʀsɪᴀɴ (Saeed Kobraiai): آقا و خانم دورسلی ساکن خانهی شمارهی چهار خیابان پریوت درایو بودند. خانوادهی آنها بسیار معمولی و عادی بود و آنها از این بابت بسیار راضی و خشنود بودند.

Gᴇʀᴍᴀɴ: Mr. und Mrs. Dursley im Ligusterweg Nummer 4 waren stolz darauf, ganz und gar normal zu sein, sehr stolz sogar.

Hᴀᴡᴀɪɪᴀɴ: Ua ha’aheo ‘o Mr Iāua ‘o Mrs Dursley o Helu ‘Ehā, Ala Pilikino, i ka ha’i aku he po’e ma’amau nō Iāua, mahalo nui loa.

Iᴄᴇʟᴀɴᴅɪᴄ: Dursleyhjónin á Runnaflöt númer fjögur hreyktu sér gjarnan af því að vera sérdeilis og algerlega eðlilegt fólk.

Iʀɪsʜ: Bhí cónaí ar mhuintir Dursley in uimhir a ceathair Privet Drive, agus é le maíomh acu go raibh said an-normálta go deo, agus iad breá sásta de.

Sᴘᴀɴɪsʜ: El señor y la señora Dursley, que vivían en el número 4 de Privet Drive, estaban orgullosos de decir que eran muy normales, afortunadamente.

Yɪᴅᴅɪsʜ: מ״ר און מר״ס דורזלי, פון דער ליגוסטער־גאַס נומער פיר, האָבן שטאָלצירט מיט דעם, וואָס זיי זענער געווען אין גאַנצן נאָר־מאַל – ווי עס באַדאַרף דאָך צו זײַן

Norwegian uses a mixed strategy, translating “thank you” directly but also adding an adverb for emphasis: “Herr og fru Dumling i Hekkveien 4 var heldigvis fullstendig normale, takk.”

Translator strategy #4: Reinterpret what the Dursleys mean by “normal”

In a few translations, the Dursleys’ “thank you” seems to come in response to a question about their happiness and well-being. “How are you doing today, Mr. and Mrs. Dursley?” “Quite normal today, thank you!” The effect of this reinterpretation suggests that the Dursleys are putting on a façade. They want their well-to-do neighbors to think they’re doing fine, but behind closed doors they’re anxious about what problems the Potters will bring them.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #4 (Click for drop-down list)

Bʀᴀᴢɪʟɪᴀɴ Pᴏʀᴛᴜɢᴜᴇsᴇ: O Sr. e a Sra. Dursley, da rua ados Alfeneiros, no 4, se orgulhavam de dizer que eram perfeitamente normais, muito bem, obrigado.

Cᴢᴇᴄʜ: Pan a paní Dursleyovi z domu číslo čtyři v Zobí ulici vždycky hrdě prohlašovali, že jsou naprosto normální, ano, děkujeme za optání.

Gᴀʟɪᴄɪᴀɴ: O señor e a señora Dursley, do número catro de Privet Drive, gabábanse de ser normais de todo, moitas gracias.

Hᴇʙʀᴇᴡ: אדון וגברת דרסלי, דיירי דרך פריווט מספר ארבע, ידעו לדוות בגאווה שהם נורמליים — ותודה ששאלתם.

Jᴀᴘᴀɴᴇsᴇ: プリベット通り四番地の住人ダーズリー夫妻は、「おかげさまで、私どもはどこからみてもまともな人間です」と言うのが自慢だった

Only a few translations use this strategy. It’s unclear whether it’s an attempt to salvage the phrase “thank you very much” or if they translator misinterpreted the intended meaning of both “normal” and “thank you very much.” It might depend from translator to translator as well.

Translator strategy #5: Remove the phrase entirely.

Some translators identified that “thank you very much” is completely unnecessary in the sentence, and it can be cut if it causes them trouble. Cutting the phrase sidesteps the problem altogether and provides an easy way out for the translator. But the removal does change the tone of the narration—away from one that offers the reader a vantage point from Mr. Dursley’s perspective and towards a more omniscient one.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #5 (Click for drop-down list)

Bᴜʀᴍᴇsᴇ (Myanmar; Kaung Myat Loon Taw): ပရီဗက်ဒရိက်လမ်း အိမ်အမှတ် (၄) တွင် နေထိုင် ကြသော မစစတာနင့် မစစဒါစခလတို့မာှ သာမန်လူများ ဖြစ်ရခြင်း အတွက် သူတို့ကိုယ်သူတို့ ဂုဏ်ယူတြသည်။

Dᴀɴɪsʜ: Hr. og fru Dursley fra Ligustervænget nummer fire var Ganske stolte over, at de var helt og aldeles normale.

Gʀᴇᴇɴʟᴀɴᴅɪᴄ: Aappariit Dursleykkut Ligustervænget normu 4-meersut tulluusimaarutigaat inuttut nalinginnaalluinnartuunertik.

Hɪɴᴅɪ: प्रिवित ड्राइव के मकान नंबर चार में रहने वाले मिस्टर और मिसेज़ डर्स्ली गर्व से कहते थे हम तो पूरी तरह सामान्य लोग हैं |

Hᴜɴɢᴀʀɪᴀɴ: A Privet Drive 4. szám alatt lakó Dursley úr és neje büszkén állíthatták, hogy köszönik szépen, ők tökéletesen normálisak.

Lᴜxᴇᴍʙᴏᴜʀɢɪsʜ: De Mr an d’Mrs Dursley aus der Kellechholzstroos Nummer véier waren houfreg drop, soen ze kënnen, dass si ganz normal waren.

Mᴀʀᴀᴛʜɪ: प्रिव्हिट ड्राइव्हच्या चार नंबरच्या घरात राहणारे मिस्टर आणि मिसेस डर्स्ली मोठ्या ताठ्यानं सांगायचे की, आम्ही तर बाबा अगदी साधीसरळ माणसं आहोत.

Sᴡᴇᴅɪsʜ: Mr och Mrs Dursley i nummer fyra på Privet Drive var med rätta stolta över att kunna säga att de var helt normala.

The Dutch and Frisian translations take a unique approach that removes the phrase, but replaces it effectively by disconnecting the clause (“proud to say they were perfectly normal”) from the first sentence and attaching it to the second. This lends focus to their pride in being normal, much in the same way as strategy #3 does. The Arabic translator took a similar approach as well.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #5b (Click for drop-down list)

Aʀᴀʙɪᴄ: تفجر أسرة (درسلى) التي تقيم في المنزل رقم أربعة بشارع (بريفت درايف) بأنها أسرة طبيعية تمامًا..وهم كذلك فعلاً، لم يكن أحد ليتصور أن تتورط هذه الأسرة في أي أمور غريبة أو غامضة.

Dᴜᴛᴄʜ: In de Ligusterlaan, op nummer 4, woonden meneer en mevrouw Duffeling. Ze waren er trots op dat ze doodnormaal waren en als er ooit mensen waren geweest van wie je zou denken dat ze nooit bij iets vreemds of geheimzinnigs betrokken zouden raken waren zij het wel, want voor dat soort onzin hadden ze geen tijd.

Fʀɪsɪᴀɴ: Yn ‘e Ligusterleane, op nûmer 4, wennen Mûzema en de frou. Se wienen der grutsk op dat se hiel gewoan wienen en as der oait minsken west ha, dêrst fan tinke soest dat se noait by wat heimsinnichs of nuvers belutsen reitsje soenen, wiewol, want datsoarte flauwekul hienen se net oan tiid.

Translator strategy #6: Alternative expressions of indignation

One less common strategy, which I personally prefer, is to replace the “thank you very much” clause with a more native expression of indignation. This ultimately preserves the reader’s impression of the Dursleys as rigid and uptight, keeps the perspective of the narrative in the vantage point of Mr. Dursley, and overall provides a similar experience to the original English sentence.

Sᴛʀᴀᴛᴇɢʏ #6 (Click for drop-down list)

Bᴏsɴɪᴀɴ: Gospodin i gospođa Dursley s broja četiri, Privet Drive, ceste biser-drveta, bili su ponosni što za sebe mogu reći da su savršeno normalni, ako bi se ko i usudio da upita.

Lᴀᴛɪɴ: Dominus et Domina Dursley, qui vivebant in aedibus Gestationis Ligustrorum numero quattuor signatis, non sine superbia dicebant se ratione ordinaria vivendi uti neque se paenitere illius rationis.

Mᴀᴏʀɪ: Whakahī ana a Mita rāua ko Miha Tūhiri, nō te kāinga tuawhā i te Ara o Piriweti, ki te kī he tino māori noa iho nei rāua – kia mōhio mai koe.

So for me, of the dozens of translations listed in this post, only the Bosnian, Latin, and Maori translations truly capture that first sentence in Harry Potter.

Lastly, it should be mentioned that the Thai translation also uses an alternative expression, but one that expresses desperation rather than indignation: นายและนางเดอร์สลีย์เจ้าของบ้านเลขที่สี่ ซอยพรีเว็ต ภาคภูมิใจนักที่จะบอกว่าพวกเขาเป็นคนปกติธรรมดาที่สุด เชื่อเขาเลย! No really! We are normal! We swear! Unlike the other translations of this strategy, however, it alters the reader’s image of the Dursleys much in the same way as strategy #2 above.

So, for me, of the dozens of translations listed in this post, only the Bosnian, Latin, and Maori translations truly capture that first sentence in Harry Potter as the story was originally written. What’s your favorite translation?

This was a little preview for you of how interesting the translation of Harry Potter can be! Leave a comment or a message and let me know what you thought. What did you like and what would you like to see more of in future posts?

Leave a Reply