Home

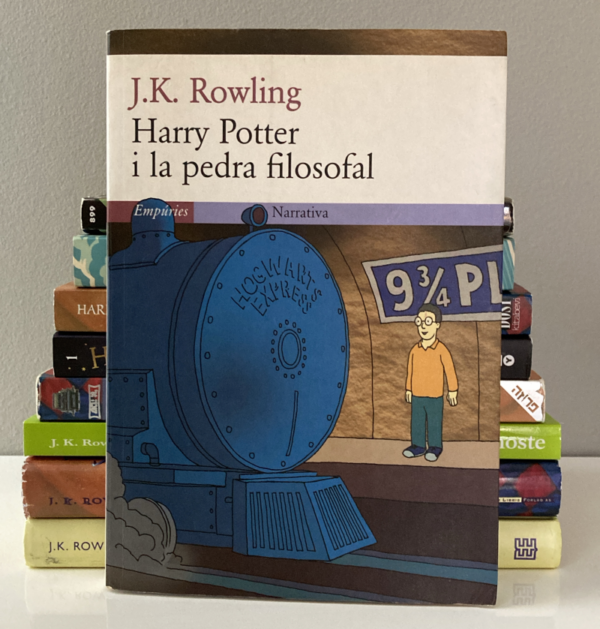

-

Gringotts Break-In: Catalan newspaper clippings

At the end of chapter 8 of Philosopher’s Stone, Harry finds a newspaper clipping in Hagrid’s hut about the Gringotts break-in. In the Catalan translation, Laura Escorihuela Martínez changed the final paragraph in such a way that it reads a bit more like a formal newspaper than the English original.

As a refresher, here’s how the newspaper article reads in the original English:

GRINGOTTS BREAK-IN LATEST

Investigations continue into the break-in at Gringotts on 31 July, widely believed to be the work of Dark wizards or witches unknown.

Gringotts goblins today insisted that nothing has been taken. The vault that was searched had in fact been emptied the same day.

“But we’re not telling you what was in there, so keep your noses out if you know what’s good for you,” said a Gringotts spokesgoblin this afternoon.In Catalan it reads:

Intent de robatori a Gringotts: continuen les perquisicions

Continuen les investigacions sobre l’intent de robatori a Gringotts el passat 31 de juliol. Es confirma la creença que va ser obra de bruixes o bruixots del mal.

Avui els goblins de Gringotts han insistit a dir que els lladres no s’havien endut res. La cambra de seguretat que buscaven havia estat buidada prèviament aquell mateix dia.

El portaveu del banc ha anunciat aquesta tarda que no revelaran què hi havia a la cambra de seguretat i ha aconsellat als periodistes que «no fiquin el nas on no l’han de ficar».

Translation into English:Robbery Attempt at Gringotts: Searches Continue

The investigations into the robbery attempt at Gringotts this past 31 July continue. The belief that it was the work of evil witches or wizards is confirmed.

Today the goblins of Gringotts insisted that the thieves did not take anything. The vault they searched was emptied earlier that same day.

The bank’s spokesperson announced this afternoon that they will not reveal what was in the vault and advised journalists to “not put their noses where they don’t belong.”

The difference in the third paragraph, which minimizes the quotation and focuses around a public statement from the bank’s spokesman, feels much more like what you would read in a newspaper. -

The Sphinx’s Riddle: Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, and Icelandic

A recent episode of Dialogue Alley brought up a scene from the Goblet of Fire where a sphinx offers Harry a riddle:

First think of a person who lives in disguise,

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (J.K. Rowling)

Who deals in secrets and tells naught but lies.

Next, tell me what’s the last thing to mend,

The middle of middle and end of the end?

And finally give me the sound often heard

During the search for a hard-to-find word.

Now string them together, and answer me this,

Which creature would you be unwilling to kiss?The riddle is highly dependent on the English language and cannot be translated easily. Brock (who, by the way, has a phenomenal Harry Potter translation food series on his Instagram) explained in the episode how the riddle is treated in Basque. In this post, I want to highlight a couple other interesting examples of how the riddle has been adapted for a new language and a new language community.

But first, a quick housekeeping note to those of you who have been following Potter of Babble with regularity:

Because we’d like to deliver you content frequently—and quality content at that—we’ll aim to do a long post and three brief posts per month. The long posts will delve into those deep dives, like the post on the Uyghurs and their Harry Potter as well as the six most common translation strategies for the opening sentence of the series. Brief posts (as this one was at least intended to be) will get into the nitty gritty minutiae of translation, highlighting very specific translations. All posts, both long and brief, will help you appreciate the books you own and the books you’d like to add to your collection.

As usual, leave us feedback and let us know what you enjoy and what you’d like to see more of!

Now let’s take a look at the riddle in English, Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, and Icelandic.

J.K. Rowling’s English riddle

First, let’s break down the English poem.

First think of a person who lives in disguise, who deals in secrets but tells naught but lies.

The answer Harry settles on: a SPY.

Next, tell me what’s the last thing to mend, the middle of middle and end of the end?

This part is my favorite, just because the answer is literally spelled out for you if you’re just looking for it. It’s the letter D.

And finally give me the sound often heard during the search for a hard-to-find word.

This one’s already a bit of a stretch for us Americans. Harry pronounces the answer for us, luckily. It’s “Er” (as in “Uh“).

Now string them together, and answer me this, which creature would you be unwilling to kiss?

String them together to get a creature? SPY + D + Er. SPYDer. Spider.

Spanish’s Spain riddle by Adolfo Muñoz García and Nieves Martín Azofra

Now let’s look at how the riddle is handled in Spanish!

The riddle in Spanish comes as part of the third leg of the Torneo de los Tres Magos—Tournament of the Three Wise Men. The Tres Magos (Three Wise Men) refers to the Magi who journeyed from Persia to Judea to visit the infant Jesus Christ and bestow gifts upon him. In Spain and throughout the Spanish-speaking world, the Tres Magos are a prominent part of the Yuletide as the ones who bring gifts to children (rather than Santa Claus).

Could it be said that the Three Wise Men, Balthazar, Caspar, and Melchior, were also the progenitors of Hogwarts, Beauxbatons, and Durmstrang?

Statues of the Three Wise Men (Spanish: Tres Magos), Balthazar, Caspar, and Melchior. In Harry Potter y el cáliz de fuego (the Spanish edition of Goblet of Fire translated by Adolfo Muñoz García and Nieves Martín Azofra), the Three Wise Men are the three wizards referenced in the name of the “Triwizard Tournament.” But back to the riddle! Spanish takes an approach that relies on Spaniards’ knowledge of geography. Let’s take a look.

Si te lo hiciera, te desgarraría con mis zarpas,

Harry Potter y el cáliz de fuego (Adolfo Muñoz García and Nieves Martín Azofra)

pero eso sólo ocurrirá si no lo captas.

Y no es fácil la respuesta de esta adivinanza,

porque está lejana, en tierras de bonanza,

donde empieza la región de las montañas de arena

y acaba la de los toros, la sangre, el mar y la verbena.

Y ahora contesta, tú, que has venido a jugar:

¿a qué animal no te gustaría besar?The crux of the clue lies in these lines:

Donde empieza la región de las montañas de arena y acaba la de los toros, la sangre, el mar y la verbena.

[The answer is found] where begins the region of the sandy mountains and where ends that of the bulls, the blood, the sea and the verbena festival.

Harry reasons: the land of the bulls, the blood, the sea and the verbena festivals is Spain (España). The end of España is ña. The region of the sandy mountains must be Morocco, or the Maghreb, or Arabia. The beginning of Arabia is ara.

Use ara for the beginning and ña for the end to get to the answer: araña (spider). How simple!

That’s pretty specific to Spain, however, and I’m curious whether the other regional Spanish translation variants use the same riddle. If your Spanish edition uses a different riddle, let us know in the comments!

Liz Wyler’s Very *Brazilian* Portuguese

The riddle in the Spanish edition keeps the answer the same, but changes the riddle substantially. Liz Wyler, the translator of Harry Potter into Brazilian Portuguese, changes the answer instead so that it mirrors the approach of the English riddle in piecing clues together throughout the poem.

Primeiro pense no lugar reservado aos sacrifícios,

Harry Potter e o Cálice de Fogo (Liz Wyler)

Seja em que templo for.

Depois, me diga que é que se

desfolha no inverno e torna a brotar na primavera?

E finalmente, me diga qual é o objeto que tem som,

luz e ar e flutua na superfície do mar?

Agora junte tudo e me responda e seguinte,

Que tipo de criatura você não gostaria de beijar?Like in English, the instructions for solving the riddle are clear: Agora junte tudo… “Now put everything together…” So we can again look at the poem by each couplet:

Primeiro pense no lugar reservado aos sacrifícios, seja em que templo for.

First think of the place set aside for sacrifices, no matter the temple.

Harry makes a guess: it’s either um altar (an altar) or uma ara (an altar stone).

Depois, me diga que é que se desfolha no inverno e torna a brotar na primavera?

Then, tell me what is it that sheds leaves in the winter and resprouts in the spring?

This one is straightforward, but vague. Harry’s left with a list of possibilities: árvores (trees), galhos (twigs), rama (branch).

E finalmente, me diga qual é o objeto que tem som, luz e ar e flutua na superfície do mar?

And finally, tell me what’s the thing that has sound, light and air and floats on the surface of the sea?

With some thought, Harry figures it out: uma bóia (a buoy).

He thinks through his list and strings together the possibilities: Ara… Hum… Ara… Rama… Uma criatura que eu não gostaria de beijar… Uma ararambóia! “Ara… Hm.. Ara… Rama… A creature that I wouldn’t want to kiss… An ararambóia!”

The ararambóia is known in English as the Emerald tree boa (Corallus caninus), a snake species specific to the Amazon rainforest in Brazil.

Emerald tree boa (Corallus caninus, Brazilian Portuguese: ararambóia) coiled along a tree branch. The Emerald tree boa is highlighted in the Brazilian Portuguese translation of the Harry Potter series by Liz Wyler. Apart from being a great candidate for this form of riddle, the ararambóia plays another role in the Brazilian Harry Potter canon. In Chamber of Secrets, its skin is mentioned as an ingredient in the Polyjuice Potion (in place of the skin of Boomslang, an African tree snake, in English).

Pretty cool intertextuality there!

Helga Haraldsdóttir’s Icelandic play on language

Harrison kindly lent me a look at the Icelandic riddle, which he’d asked about prior to me putting this post together. The translator employs some nice poetic devices.

Hvað kallarðu þann sem elskar hún Hera

Harry Potter og eldbikarinn (Helga Haraldsdóttir)

og höfuðfatið þungt þarf að bera?

Hvað heitir svo það sem á hvolfi er enn,

og hvílir á vörum er hugsa menn?

Síðast vér spyrjum, hvað saman safnast,

undir sófa og engum gagnast,

Settu saman svörin þrjú

og svara oss

Hvaða skepnu myndir þú

aldrei gefa koss?Hvað kallarðu þann sem elskar hún Hera og höfuðfatið þungt þarf að bera?

What do you call the one whom Hera loves and who has to wear heavy headdress?

Harry surmises: Kóng? A king?

Perhaps. Hera’s husband, Zeus, is the king of the gods. As to why Hera’s husband was chosen as a clue for royalty, well, simply put, she was chosen because Hera rhymes with bera (“to wear”).

Hvað heitir svo það sem á hvolfi er enn, og hvílir á vörum er hugsa menn?

What do you call what is still upside down and rests on the lips of those who are thinking?

This couplet is a beautiful one, with an alliteration scheme that plays quite a bit on “hv” (with near-alliteration with the “h” in heitir and hugsa and with the “v” in vörum). The pairing of á hvolfi (“[hanging] upside down”) and hvílir á (“it rests upon”) offers a contrast that’s quite satisfying for a riddle as well. This contrast is accentuated all the more by the triple entendre of á hvolfi. In contrast to “rest,” á hvolfi denotes chaos and busyness: it’s used to mean things are messed up, out of place, or out of control. Indeed, the translator intends this double reading: “What do you call what is still confused and rests on the lips of those who are thinking?” This reading anticipates Harry’s response to the clue: Uh… hef ekki hugmynd…” “Uh… I haven’t a clue…”

The third thing á hvolfi could mean is “on the ceiling,” although this meaning would not be particularly idiomatic. The image that comes to mind is something hanging from the ceiling that can also come down and land on you. Admittedly, that might be a stretch and not be the intention of the translator. But perhaps it is a clue that the answer is a spider.

Síðast vér spyrjum, hvað saman safnast, undir sófa og engum gagnast

At last we ask, what gathers together, under a sofa and is of use to nobody

This couplet takes advantage of one of my favorite grammatical features in Icelandic: the middle voice (inflected with the suffix -st in safnast and gagnast). The middle voice is a somewhat vague concept that varies from language to language. But in each language that has a middle voice, it occupies some function between the active voice (“the students gather”) and the passive voice (“the students are gathered”). In the active voice, the subject is the one doing the action. In the passive voice, the subject is the one being acted upon. In the middle voice, the subject is both doing the action and being acted upon.

To illustrate: in the active voice example of “the students gather,” the students are the ones doing the gathering. In the passive voice example of “the students are gathered,” someone else is gathering the students. In the middle voice, “the students gathered themselves,” the students are both gathering and being gathered.

The answer to this couplet is ló—lint—which happens also to be a great image for the middle voice. Lint doesn’t simply gather. Lint gathers up other lint. And lint is gathered up by other lint. It sticks to itself and builds upon itself, forming into concentrated and self-reinforcing clumps and balls.

Settu saman svörin þrjú og svara oss

Hvaða skepnu myndir þú aldrei gefa koss?Put together the three answers and tell us

Which creature would you never give kiss?Harry does so: Kóng + Uh + Ló. Kónguló. A spider!

Anyway, so much for a brief post! Leave your thoughts and comments and share with your friends! We’d all love to hear more about how your language translates this poem.

-

The Big Reveal: the rare Uyghur translation of Harry Potter I just got my hands on…

For weeks, I’ve been teasing other collectors with what rare mystery book I was able to get ahold of. Initially, I intended to reveal the book as soon as I received it. But when I opened it and found how pleasantly surprised I was by it, I decided to wait.

The reason why? I wanted to make a case for why it’s worth looking for. Few collectors own this book. And few details are known about it, save for an investigation over at Potterglot. So I thought that owning a copy put some responsibility on me to augment Potterglot’s work with some additional info!

Below, I’ll begin with a note to collectors before I provide a brief background about the language community and the language itself. Finally, I’ll give you a little taste of the translation style and discuss some text examples while providing a little sampling of wizarding names and terms. There’s a lot more to say about this book than the little preview I offer here. So if you get the chance, leave some feedback on what you enjoy from the post and whether there’s more you’d like to see!

A note to collectors and an introduction to the book

Before I get to the reveal, let me start by addressing the reasons collectors hesitate to look for this book. The first is that the legal permissions for the translation are questionable. It’s possible that Rowling and her agents never authorized it, although no definitive answer to that question has been determined. Some collectors hesitate to own an unauthorized translation because of how easy it is for anyone to produce, and especially without any consideration toward quality or seriousness.

Whether this one has appropriate permissions, it is published by a reputable and established publisher and has gone through the proper legal channels for its locality. It also appears to be a formal attempt at translation and publication, and the translation itself reads really well. On the Spellman Spectrum, it rates 52.3, meaning it’s an enjoyable read on par with the German, Catalan, and Portuguese translations. Unauthorized translations tend to be of lower quality and rate much lower as well.

The other hesitation among collectors is the cover art. Or rather, the lack of it. That’s a big turn off for some collectors. But the book quality itself is otherwise amazing. When I held it in my hands, I was pleasantly surprised. The binding and the pages are decent quality, and it feels very nice to hold the book and flip through its pages. It’s probably more pleasant, in fact, than any other softcover Harry Potter book I own. It Exceeds Expectations in many regards.

If you’re the type of collector who collects some unauthorized translations, I’d highly recommend adding this one to your collection. Not only because it approaches professional quality, but also for purposes of language preservation. More on that below, but first the big reveal…

Harry Potter (Kharri Pottir) in the Uyghur language, translated by Alimjan Azat. It’s Uyghur! Shout out to Jenny, who was the first to guess it.

The title of this book is simply Kharri Pottir and it was translated by Alimjan Azat. He seems to be a prolific translator, with The Da Vinci Code (or Davinchining Măkhpiyiti) among his other major sellers. The book was published in 2012 by a reputable publisher called Xinjiang Juvenile Publishing House, which has published more than 20,000 books in Uyghur, Chinese, and Kazakh.

It’s worth taking a moment to mention that there is a strong preference among Uyghurs to spell their ethnonym with a “y,” which more accurately reflects that the y in the OOY-ghur pronunciation is a consonant rather than a vowel. I’ll admit that I don’t fully understand why there seems to be an aversion to the “Uighur” spelling, at least among human rights activists, but these seemingly small matters become very important for communities that face existential threats to their communal identity.

Who are the Uyghurs? And why are Uyghur books becoming precious?

Map of China, showing the distribution of Uyghur speakers in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Province. Light red indicates desert region with few inhabitants. The Uyghurs are frequently in the news these days, at least in English-language media. They live mainly in northwestern China in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Province, which has become a focal point in the discussion of human rights in China.

Map of approximate extent of the Uyghur empire in the 9th century. Although you may not have heard much about the Uyghurs before 2018, they’re one of the major ethnic groups in Central Asia, where they commanded an empire in the 8th century. It was led by a khagan, the military commander charged with conducting foreign affairs, alongside a domestic policymaker appointed from among a council of tribal leaders. The empire flourished after its conversion to Manichaeism attracted merchants, artisans, and specialists of the Manichaean faith to relocate from Persia and nearby regions. It was at that time that the Uyghurs adopted the Manichaean script and adapted it for their own language. That famously vertical script, or at least a version of it, remains in use today by speakers of Mongolian and Manchu.

Text example of Manchu language. The vertical Manchu and Mongolian alphabets are derived from the Old Uyghur alphabet. The wealth attained by the Uyghurs during this period, by both material and cultural measures, ensured the elites’ survival after the fall of the empire from Kyrgyz invasions in the mid-9th century. Only years later, a Uyghur kingdom was re-established in modern Xinjiang. Xinjiang had previously been under the peripheral control of the Uyghur rulers, but was now at the center of their power. The kingdom continued to be a powerhouse for Uyghur cultural production until the 13th century, when it was overtaken by the Mongols.

It was during these two eras that the rich traditions of Uyghur culture were augmented by a melting pot of the world’s most influential literary heritages, including those of Persia, India, and even the distant Greeks. According to Rian Thum in his book The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History, the Uyghurs have a national hero, Siyawushullah, whose tomb near Kashgar serves as a place of pilgrimage. The legendary figure is clearly derived from the Siyavash of the Shahnameh, the Persian national epic, but adapted in a way that represents centuries of the Uyghurs’ historical experience.

The Uyghurs slowly and gradually converted to Islam over a period of centuries, first from exposure to Muslim elites who migrated to their kingdom and later from socioeconomic and political pressure as the governing elites themselves became Muslim. With access to the Qur’an and to Islamic literature now a priority among the well-educated, the Uyghurs switched to the Arabic script for writing their language. Still, only around the 18th century or so did the rich folk and literary traditions of the Uyghurs start becoming Islamicized—relatively late for an Islamic people.

Unfortunately, Uyghurs today are losing access to their language and centuries of literature. One factor is a major spelling reform in the 20th century. The changes improved literacy overall. By matching the written language to pronunciation, it became much more simple for people to learn to read and write in Uyghur. But the differences to the old spelling conventions were so great that it became very difficult for literate Uyghurs to read old books and manuscripts.

More recently, policies by China’s government have begun suppressing the Uyghur language. Officially and historically, China has protected and promoted Uyghur literacy and education. But tensions between Beijing and the Uyghurs go back centuries and, geopolitically, Xinjiang is a very important region for the Chinese government to keep under its control. The relationship is not inherently hostile. But Uyghur and Chinese interests have often been at odds with one another.

China, especially under the initiatives of Xi Jinping, now views language policy and education as a big part of the problem (and thus also part of the solution). It has systematically transitioned education among the Uyghurs away from Uyghur language schools and toward schools where the language of instruction is Mandarin Chinese—all with the intention of integrating the Uyghurs into the socioeconomic fabric of China. Over the last 5 years or so, a lot of evidence has emerged indicating that China’s strong-handed education policies are both coercive and repressive.

In all of this, Uyghur literacy is being suppressed. Uyghur children are not being taught how to read the language and even the most harmless of Uyghur books are being banned. In the past couple years, some people have reported that the only Uyghur-language books they can now find in bookstores in Xinjiang are translations of Xi Jinping’s book. What that means for books like Kharri Pottir, which are translated directly from approved Chinese publications and whose content is well-known to Chinese officials, is unclear. But in an era of language repression, it’s always a good idea for collectors in safe countries to hold on to whatever books they have in that language.

Some comments on the Uyghur language

The Uyghur language is a Turkic language of at least 10 million native speakers, and as many as 150 million people can understand it to some extent. It’s a cousin of Turkish, and the two languages enjoy such a high degree of mutual intelligibility that speakers of either language can pick up most words in the other. It’s even more closely related to Uzbek, a language of 25 million speakers, and speakers of Uzbek and Uyghur can converse freely with one another without much difficulty. Uyghur also enjoys some mutual intelligibility with Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, and a few other languages.

As mentioned above, Uyghur primarily uses an adapted Arabic alphabet. It underwent a major spelling reform in the 20th century which introduced a more regular system of phonetic vowels.

Uyghur translation

Let’s take a look at the opening lines of Kharri Pottir. I like to look at that first sentence in Harry Potter translations not only out of general interest, but because it’s linguistically fascinating and complex. That’s no less true for Uyghur, which takes a somewhat unique approach:

مەبۇدە كوچىسىدىكى تۆتىنچى نومۇر لۇق قورۇدا ئولتۇرىدىغان دېسلى ئەر – خوتۇنلار هەمىشە ئۆزلىرىنى توليمۈ قائىده-يوسۇنلۇق ئائىلە دەپ پەخىر لىنەتتى، ئەمەلىيەتتىمۇ ئۇلار قائىده-يوسۇنغا بەك ئېتىبار بېرەتتى

Măbudă kochisidiki tötinchi nomur luq qoruda olturidighan Desli ăr – khotunlar hămishă öz lirini tolimü qa’idă-yosunlüq a’ilă dăp păkhir linătti, ămăliyăttimu ular qa’idă-yosungha băk etibar berătti.

Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, who live at Number 4 Mabuda Street, were always proud of themselves as a very well-mannered family—in fact, they were very disciplined.

Kharri Potter (Alimjan Azat)In the post linked above, I identified six common strategies translators have used to interpret this sentence. Azat uses the third strategy in his Uyghur translation: he replaces the phrase “thank you very much” with an emphatic repetition (“in fact, they were very disciplined”) to drive home the point of how well-mannered the family is.

Notice that Azat also takes a creative approach to interpret “perfectly normal.” I took some liberties in translating qa’idă-yosun and qa’idă-yosunluq as “well-mannered” and “disciplined.” But the compound phrase generally refers to someone with an upright upbringing and the ability to navigate proper etiquette in social occasions. It’s a good application of the so-called “skopos principle” in translation theory: translating not only the words but also the cultural implications. To be “perfectly normal” in Uyghur culture is to have that proper upbringing and etiquette.

An interesting feature about the translation, as Potterglot first pointed out, is that it is clearly translated from the Simplified Chinese version of Philosopher’s Stone as translated by Su Nong. In fact, the Mabuda Street mentioned above is the first thing to betray the Chinese background. The word măbudă in Uyghur means “female idol.” The Chinese word for privet, 女贞, literally means female idol.

But evidence of translation from Chinese really comes out in the translation of proper nouns and other wizarding terms that are transliterated rather than translated. Below are some examples of names, words, and phrases that directly reflect the Mandarin pronunciation of the names and words found in Su Nong’s Chinese translation of Philosopher’s Stone.

English Uyghur Uyghur (transliterated) Simplified Chinese (pinyin) Albus Dumbledore ئاربوس دىمبورىدو Arbus Dimborido Ābùsī Dèngbùlìduō Minerva McGonagall مىلۋا ماك Milva Mak Mǐlēiwá Màigé Hagrid هېيگىر Heygir Hǎigé Draco Malfoy دېلاك مولفۇر Delak Molfur Délākē Mǎ’ěrfú Quirrell چيررو Chirro Qíluò (q pronounced like ch) knut نارد nard nàtè sickle شىك shik xīkě (x pronounced like sh) wingardium leviosa يۇهادىم، لىۋىئوۋسا yuhadim livi’ovsa yǔjiādímǔ lēiwéi’àosà Transliteration of names in the Uyghur (Alimjan Azat) and Chinese (Su Nong) translations of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone These examples show just how close the Uyghur names are to the Chinese names. Don’t be distracted by the r’s and l’s that are seemingly out of place—that’s all more or less just a fluke of accent. In fact, the “r” in nard (“knut”) actually strengthens the claim that nard comes from Mandarin nàtè. In northern accents of Mandarin, the syllable nà is pronounced nàr (a phenomenon sometimes called erhua). Direct translation from Mandarin is the best explanation for where that “r” came from in the Uyghur translation.

Some other tell-tale signs in these examples: the insertion of that second i in Dimborido (Dèngbùlìduō); the abbreviation of Mak (Màigé) from “McGonagall”; Heygir and Hǎigé are pronounced almost identically, despite the difference in spelling, and neither one is close to “Hagrid.”

In a few cases, direct translation from Chinese is betrayed by the use of an exact calque:

English Uyghur Uyghur (transliterated) Uyghur translation Simplified Chinese Simplified Chinese translation beater توپ ئۇرغۇچى top urghuchi ball batter 击球手 ball batter chaser توپ قوغلىغۇچى top qoghlighuchi ball chaser 追球手 ball chaser golden snitch توپ ئالتۇن رەڭ ئۇچقۇر قاراقچى top altun răng uchqur qaraqchi golden flying-bandit ball 金色飞贼 gold flying-bandit ball Remembrall خاتىرە شارىكى khatiră shariki memory ball memory ball You-Know-Who سىرلىق ئادەم sirliq adăm Mystery Man Mystery Man Translations of Harry Potter wizarding terms in Uyghur (Alimjan Azat) and Chinese (Su Nong) The clearest examples are the translations for “golden snitch” and “You-Know-Who,” which completely differ from the original English but whose Uyghur and Chinese translations match one another.

Although it’s clear that the translator used the Su Nong translation as his guide, he did not rely dryly on the Chinese text. He introduced some creativity of his own. Peeves’ name, for example, is translated as Shăytanchaq (“Demonic”). The word for Muggle (Máguā in Chinese) was translated as Hangvaqti (“Befuddled”). And even the opening sentence provided at the start of this section employs a different translation strategy from the Chinese. (While Azat’s Uyghur uses the third strategy of emphasizing “perfectly normal,” Su Nong’s Chinese translation uses the second strategy of reinterpreting the meaning of “thank you very much.”)

Conclusion

Whether or not Azat’s Uyghur translation acquired appropriate permissions is unclear, but it’s worth having in your collection. Not only is the publisher well-established and the translator professional and experienced, the translation itself is quite good and unique. The book is getting harder to find, perhaps because of a broader crackdown on Uyghur literature. But it’s a good addition to your collection, not only because it’s as close to an authorized edition as seems possible for the region and language, but also for the sake of literary preservation.

-

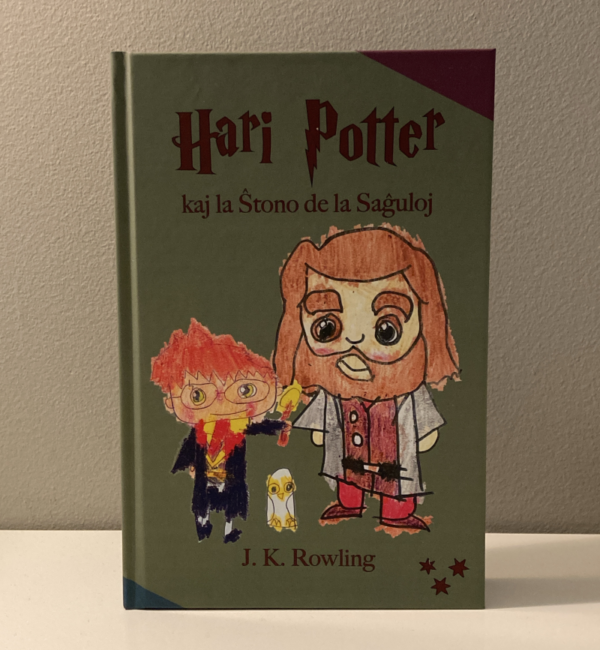

Harry Potter in a made-up language? The Esperanto translation!

“Jes…” diris Zomburdo reve. “Strange la homaj mensoj funkcias, ĉu ne? Profesoro Snejp ne povis toleri tion, ke li ŝuldas al via patro… mi ja kredas, ke li tiom klopodis por protekti vin ĉijare, ĉar li sentis, ke tio kvitigus la aferon inter li kaj via patro. Tiam li povus denove malamadi la memoron de via patro senĝene…”

Hari Potter kaj la Ŝtono de la Saĝuloj (George Baker and Don Harlow)

Hari klopodis kompreni, sed tio faris lian kapon bategi, do li ĉesis.

“Kaj sinjoro, restas sola demando…”

“Nur tiu sola?”

“Kiel mi ekhavis la Ŝtonon el la spegulo?”

“Ah, nun mi ĝojas, ke vi demandas tion. Tio estis unu el miaj pli geniaj ideoj, kaj inter ni mi konfesas, ke tiu signifas multon. La solvo estis tia: nur tiu, kiu deziras trovi la Ŝtonon — trovi ĝin, sed ne uzi ĝin — nur tiu povis ekhavi ĝin, alie oni vidus sin farante oron aŭ trinkante la Eliksiron de la Vivo.Those of us who collect Harry Potter translations often talk about how few people have gotten to read Harry Potter in languages like Gujarati or Nepali: so few copies even exist in those languages. But if there’s ever been a translation that’s widely available but has never been read, it’s most likely the Esperanto edition! At least cover-to-cover.

What even is Esperanto?

Esperanto is a constructed language, not unlike High Valyrian from Game of Thrones or Elvish from Lord of the Rings. That comparison is a little unfair, though. High Valyrian and Elvish were made up just for fun. Esperanto was created with a serious purpose.

Invented by L. L. Zamenhof (self-styled “Doktoro Esperanto,” which means “Dr. Hoping”), Esperanto is an international language easy enough for everyone to learn, whether their native language is English, Italian, German, or Polish. The grammar is very simple. No verb conjugations. No grammar. Its words are recognizable and easy to pronounce.

ِAnd the easy language caught on! There are thousands of people who actually speak this made-up language. You can learn it at Duolingo. William Shatner starred in Incubus, the most well-known of many Esperanto-language films. George Soros is rumored to be a native speaker. His father was a dedicated Esperantist; the family name Soros is Esperanto for “We Shall Soar.”

So much has been written in Esperanto that Google Translate has a module for the language. In a previous post, we mentioned that only several dozen languages (of the thousands spoken today) have enough literature for Google Translate to work.

The story behind Harry Potter in Esperanto

It’s ultimately no surprise that people would endeavor to translate Harry Potter into Esperanto. People use it, people believe in it, and it offers opportunity for language practice. And although I joked that probably nobody has read the translation cover-to-cover, I wouldn’t doubt that hundreds of people have read at least the first chapter or two.

The translators of the Esperanto edition were George Baker and Don Harlow, active participants in an organization known as Esperanto-USA, which is a 501(c)(3) organization that aims to promote education in Esperanto. The translation was reviewed and edited by other Esperantists, and a serious attempt was made to have the translation published. Rowling’s attorneys declined to authorize its publication, however, without working through a well-established publishing house.

So the Esperantists started a website that was intended to demonstrate interest in the publication. In 2007, its petition had more than 600 signatures, 460 of whom claimed either fluency or competence in Esperanto. If each one of those signatories were to buy the Esperanto edition, it would be roughly as successful as at least two other translations: Asturian and Greenlandic. Who knows how many more people would buy it just out of general interest in either Esperanto or Harry Potter book collection. (I’d definitely buy it!) One thing’s for certain, though: it would be a real challenge to market and to identify bookstores that could display and successfully sell the edition.

Translation style of Hari Potter kaj la Ŝtono de la Saĝuloj

Now let’s talk a little about the text itself. Like a handful of other foreign editions, the Esperanto translation relies on footnotes to mention cultural references. And because Esperanto is a constructed language, this translation also uses footnotes to explain certain neologisms and obscure words that other Esperantists may not have previously encountered.

One excellent use of footnotes is in the translation of Halloween as Halovino: “Halovino (angle: Hallowe’en) fest je la 31a de oktobro, ĉefe en Britio kaj Nord-Ameriko, kiam oni tradicie maskaradas kiel gesorĉistoj, fantomoj, aŭ similaj. Esperante: antaŭvespero de ĉiusanktula tago.”

This fits with the translators’ express goal of preserving the British context of the novel. They explain Halovino in the footnote, particularly the special nature of Halloween in the Anglosphere. It then goes on to provide the native Esperanto phrase for “All Hallow’s Eve” (antaŭvespero de ĉiusanktula tago), even though the translators chose to borrow Halovino from English. That choice to borrow the English word “Halloween” and explain it with a footnote allowed the translation to retain the cultural context behind the word, which would have been obscured by using the native Esperanto phrase for “All Hallow’s Eve.”

But naturally translators who rely on footnotes are going to over-rely on them. An example of this occurs already in the fourth footnote of the translation. In the English edition, Uncle Vernon hums a song called “Tiptoe Through the Tulips.” The song title is translated literally into Esperanto as “Paŝetu en Tulipoj.” The accompanying footnote explains that “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” is a well-known song in English by Tiny Tim. Again, this served the aim of preserving the British context. But in that case, they should have just kept the title in English—especially if they were going to explain the reference in a footnote!

I’d argue that the footnote reference to the Tiny Tim song was too specific to serve the reader anyway. Sure, the song is a bit silly and readers benefit from knowing how frolicsome the song actually sounds. But the real effect for the reader comes from the title, not the sound of the song. The footnote distracts the reader from the intended takeaway of a very passing moment: Vernon Dursley humming about gaily in the garden to a happy tune. It didn’t matter for the reader how dainty the real song sounds. It matters how dainty the alliterative title came off. (After all, how many of us were even aware of the Tiny Tim song when we read Harry Potter as kids?)

The choices for proper nouns, meanwhile, are either hit or miss. Ron Weasley becomes Ron Tordeli, a believable name that rolls off the tongue (although hardly British). But Neville Longbottom becomes an awkward Neville Longejo. The translators also missed many opportunities to take creative license, such as “Kvidiĉo” (Quidditch) and “Skabro” (Scabbers), where the English name was simply adapted for Esperanto morphophonology.

Some idiomatic phrases come off dry in the translation. When the goblins of Gringotts warn journalists to keep “their noses out” of Gringotts’ affairs, the quite literal interpretation of “do tiru viajn nazojn el la afero” just does not have the same effect. On the other hand, if that’s what lacks most in a translation of a novel into a constructed language, I would still count that translation a pretty impressive project!

Overall the rating of the Esperanto translation on the Spellman Spectrum is 45.5 (at the time of this post). That’s a fairly successful score for what the translators wanted to achieve: a translation that’s easy and straight-forward for an intermediate language learner. At the same time, the score reflects a moderate degree of creativity and innovation, offering the occasional Easter egg, if you will, for the Esperanto student to discover.

-

A tale of trolls and goblins: the Low German “Puk” in Harry Potter

Today, we’re going to explore an example from Harry Potter un de Wunnersteen in Low German where the translators’ choices have significant implications for world-building. In this case, the translators, Hartmut Cyriacks and Peter Nissen, chose to use the same word (Puk) for both the goblins at Gringotts and the troll in the dungeon. While the descriptions of the two Puken make it clear that they cannot be the same type of creature, the reader assumes some sort of association between the two creatures, whether they be two races of the same type of creature or just belong to a broad category of creatures.

Regardless of what the connection between these two creatures is, we’ll see that the use of the same word for both creatures has clear implications—most notably, that some wizards and witches hold disparaging views of the Puken at Gringotts.

What’s a Puk? (And where to find them)

The Puk (in English, “puck”) is a mythological creature known throughout the northern European plains, Great Britain, and Ireland. Its description tends to be vague. It dwells among humans but goes undetected, so it’s thought to be small enough to scurry away unseen or to have the ability to take the unsuspicious form of domestic animals (cats, dogs, goats, rats…).

Puken like tidiness and they’re prone to cleaning up their living spaces, even if it’s your home and your mess. Sometimes they’ll do little favors for you, too—with your encouragement of course. They’ll expect you to leave them some nibbles or some old clothes as rewards.

They’re not above playing tricks on people. They mostly just pull harmless pranks, like tying your shoes together or pulling the blanket off you while you sleep. It gives them a good laugh and provides them with some entertainment. It can even be a sign that they feel comfort and companionship with you. But if you anger them, you’d better watch your step and leave a light on as you sleep, because they’re capable of far worse than those benign jests. Some Puken are also just bad apples who want to create havoc.

In Low German folklore, Puken have a more certain physical form than in other parts of northern Europe. They’re short, elf-like creatures with pointy hats and slippers not unlike, well, elves. They’re quite clever, and so it’s no wonder why Puk was chosen as the Low German substitute for the Gringotts goblins.

The troll in the Dungeon (or: the Puk in the Cellar)

More curious was the choice to translate “troll” as Puk as the description doesn’t fit the Low German conception of a Puk at all:

Dat sehg gräsig ut. Veer Meter hooch, mit ‘n Huut so bleek as gries Granit, dat Liev as ‘n groten Hinkelsteen, wo ‘n unheemlichen Glatzkopp op seet, de nich grötter as ‘n Kokosnutt weer. Mit dree korte Been, dicker as utwussen Eekbööm, un ünnen an platte Fööt mit dicke Hoornhuut. De Gestank weer nich to’n Utholen. In de Hand harr ‘t ‘n gewaltig grote hölten Küül, de vunwegen de langen Arms op de Eer slarr.

“It looked horrible. Four meters high, with skin as pale as gray granite, its body like a big cornerstone on which sits an unseemly bald head no bigger than a coconut. With three short legs, thicker than fully grown oak trees, and flat feet at the bottom with thick, horned skin. The stench was unbearable. In its hand it had a large wooden club, which dragged on the ground because of its long arms.”

Harry Potter un de Wunnersteen (Hartmut Cyriacks and Peter Nissen)Quite the opposite of your traditional Puk, this one is gigantic. Not only does it stand four meters tall, but each of its three(?!) short legs is thicker than a tree trunk! There is no way this particular Puk could get away with anything sneaky around your house.

But perhaps that’s why this type of Puk is lesser-known: they’re too big to live inside your walls or beneath your floor panels. They’d be quite clunky for sneaking around your house while you’re asleep. You just simply wouldn’t encounter such a gigantic Puk as commonly as one of the smaller ones that reside inside your home.

The Gringotts Puken

Now let’s take a look at how the Puken at Gringotts are described:

De Puk weer bummelig een Kopp lütter as Harry. He harr düüster Huut, ‘n plietsch Gesicht, ‘n Spitzboort un – dat full Harry op – gewaltig lange Fingers un grote Fööt.

“The Puk was about a head shorter than Harry. He had dark skin, and clever face, and a pointed beard and – Harry observed – huge long fingers and big feet.”

Harry Potter un de Wunnersteen (Hartmut Cyriacks and Peter Nissen)Not only are the Puken at Gringotts short, but they have dark skin. You’ll recall that the tall Puk in the Hogwarts cellar (Keller), as the dungeon is described in Low German, has pale, gray skin.

Are the Gringotts goblins dumb?

Clearly the Puk in the cellar and the Puken in Gringotts are not the same creature. As readers of Harry Potter un de Wunnersteen, we might suppose that both creatures are called by the same name because they’re different races of the same creature. Or we might consider Puk just to be a category of creature, not unlike how “troll” in English refers categorically to earth-dwelling creatures who may either be monstrous ogres or shy little dwarves.

But consider the consequences of lumping them into the same category:

When Harry asks what a Puk would be doing in Hogwarts a Ron responds: “De schüllt doch egentlich so dösig ween.” (“They’re supposed to be really stupid.”) In this scene, Ron doesn’t yet know whether the Puk in the cellar is the ogre-type or the dwarfish Gringotts-type. He doesn’t make any effort to distinguish between the two types, either. He just categorically dismisses Puken as dumb, necessarily implying an assumption on Ron’s part that there are no clever Puken.

As readers of this Low German-language wizarding world, we learn that at least some wizards consider the Puken in Gringotts to be dumb creatures. Whether or not they are dumb is a separate question: they’re described as having a clever face (“plietsch Gesicht“), but we also know that someone had outsmarted them by breaking into Gringotts. We might even assume that Ron calls them “stupid” out of frustration about the Gringotts break-in. But we can be quite clear that there’s disdain for the Gringotts goblins reflected in Ron’s statement.

By creating this association between the dungeon troll and the Gringotts goblins, the Low German translators demonstrate the power of translation to alter the world imagined by the reader. In this case, where the English reader is led to believe that the goblins at Gringotts are incredibly clever and admirable, the Low German reader is left with a less positive impression that they’re at least somewhat dumb and wreckless.

-

Low-resource languages: what they are and why they matter

Every so often, I like to talk about low-resource languages. They’re a matter of particular importance in today’s tech world and, for me, the topic is especially important in terms of expanding access to vital information throughout the world. So today I want to discuss a little bit about what low-resource languages are, why they matter, and illustrate an example using Harry Potter.

Google Translate, artificial intelligence, and how they work

Google Translate and other machine translators have come such a long way. You’ve especially seen this if you remember how awful it used to be: translating literally word-for-word in poorly constructed sentences and often misinterpreting the intended meaning. Nowadays, Google Translate usually gets it right.

It’s a powerful tool that’s too easily taken for granted. If you need to find information that’s only available in German, you can just copy and paste the German text into Google Translate and get the information in English. It’s a great resource for people around the world to access all sorts of important information, from the latest medical studies of a certain ailment to how to fix a car problem under the hood of your foreign-built vehicle.

At least, that’s the case if you speak one of just a couple dozen languages. The processes en vogue today for natural language processing (NLP; the type of artificial intelligence used in machine translation) rely on ginormous corpora of written language. They inform the translation by serving as models of proper language use, as written by native human speakers. It’s a brilliant concept that works very well.

Low-resource languages and their speakers are left out

But the vast majority of the world’s thousands of languages do not have ginormous corpora of written language. Some languages don’t even have a writing system, and most of those that do have a few hundred books’ worth of material in them at most. (For perspective: the number of books that have been written in English or German is in the tens of millions.) Those languages with relatively few written language samples are called “low-resource languages” because they don’t have enough resources to serve as models for natural language processing.

Speakers of these low-resource languages generally don’t have ready access to information on the latest medical advice or computing mechanics. They have to learn a second language to get much out of the internet. What’s more, because so little literature exists in these languages in the first place, they often don’t have the discourse available to talk about basic modern medicine or finance. Most languages don’t even have the sufficient vocabulary to talk about those topics.

Building meaning: Harry Potter as example

To understand this issue a little bit more, let’s take a look at this excerpt from the 7th book in the Harry Potter series, which I selected simply by opening the book to a random page. The underlined words exist as part of a discourse introduced to you by the Harry Potter series.

“I say we find a quiet place to Disapparate,” Hermione whispered.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

“Can you do that talking Patronus thing, then?” asked Ron.

““I’ve been practicing and I think so,” said Hermione.

Two Death Eaters drew their wands. The force of their spells shattered the tiled wall where Ron’s head had just been, as Harry, still invisible, yelled, “Stupefy!”This passage is meaningless to anyone who hasn’t read the whole series. It only makes sense after reading the previous six novels.

Now let’s stop and think about this. That’s a tremendous amount of information you had to consume to really appreciate the meaning of this one passage! It didn’t require any study or hard work on your part, and it was probably a lot of fun along the way.

We first learn about Disapparating in the Chamber of Secrets, when Ron explains why his parents don’t need the flying car. Harry learns to cast a Patronus in the Prisoner of Azkaban to protect himself from Dementors. Death Eaters are also mentioned in the Prisoner of Azkaban, the same novel where we start to learn Harry’s connection to a whole movement of wizards that worked to defeat them. We dive deeper into our understanding of the Patronus charm in the Order of the Phoenix, where we find it can be manipulated by well-practiced wizards and witches into a means of communication. And although simple, the Stupefy spell is introduced only in the Goblet of Fire, where the seriousness of the Dark Arts threat begins to cast its shadow.

That’s a ton of information to swallow all at once. Imagine reading Deathly Hallows before the rest of the series and having to read an article from the Harry Potter Lexicon every time a new word or character pops up.

Using Harry Potter to make low-resource languages more resourceful

But the fact that a children’s novel is able to build a discourse around a fantasy world—a set of abstract ideas that don’t even exist—is a testament to the fact that we can certainly articulate new ideas in any language. The key is building up to it, rather than introducing it all at once.

There are two ways you can build up knowledge. One is through oral education. That tends to be labor-intensive and costly, and it’s not so easy to go back and review what was said. To be fair, the accessibility of audio and video recordings has at least alleviated much of those concerns in the past decade or two.

The other method is through the written word, which survives long-term and can be easily reviewed as needed. But the type of literacy needed for useful written material requires time, patience, and stamina that readers must attain through practice.

The translation of Harry Potter into low-resource languages is one great way to give speakers of low-resource languages such practice. Not only is it proven as an enjoyable time-pass for children, but its length and its genre as a fantasy novel gives them practice in patience and stamina and in piecing together a whole new world from slow and gradual detail.

A number of low-resource languages have translated Harry Potter precisely for this reason—some more successfully than others. Frisian, Occitan, and Luxembourgish are a few. I mentioned in a previous post about how Maori was particularly successful, building a world from within Maori traditions. This should be done in more low-resource languages, while being careful not to overwhelm children with so many neologisms that they can’t keep up. That would also require more flexibility from J. K. Rowling and Warner Bros. for translators to transform the story as needed: in some cases, restrictions on translating names like “Slytherin” may even be burdensome.

Want more?

Since the topic of this post is relatively dry, I kept it intentionally brief, despite having a lot more to say. If you’re interested in learning more about anything discussed in this post, leave a comment or contact me and let me know, and I can expand on that discussion in a future post!

Meanwhile, be sure to check back weekly for new posts at Potter of Babble, and follow us on Instagram and Twitter! And don’t forget to join the discussion on our email list.

-

The 5 best translations of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone according to the Spellman Spectrum (June 2022)

Let’s take our very first look at the top-scoring translations of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone!

At the time this post was written, just under 30 editions had been rated on the Spellman Spectrum, a scale designed to rate and compare translations of the same text. That’s a pretty sizeable amount! But it also leaves us less than a third of the way through the long list of translations of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, while the Spellman Spectrum itself remains a work in progress. So expect to see revised postings of this list—perhaps once or twice a year—until the list is complete.

With that said, we can already see a broad range of ratings along the scale! Only 2 have surpassed a score of 90 (Norwegian and Maori), while 3 (French, Dutch, and Frisian) have reached a score of 80. Luxembourgish falls just short of 80 and the remaining books fall within a wide range of 22–77. So let’s take a quick look at these top-scoring translations and highlight a few things in each one! Keep an eye out for full articles on each of these editions in the future.

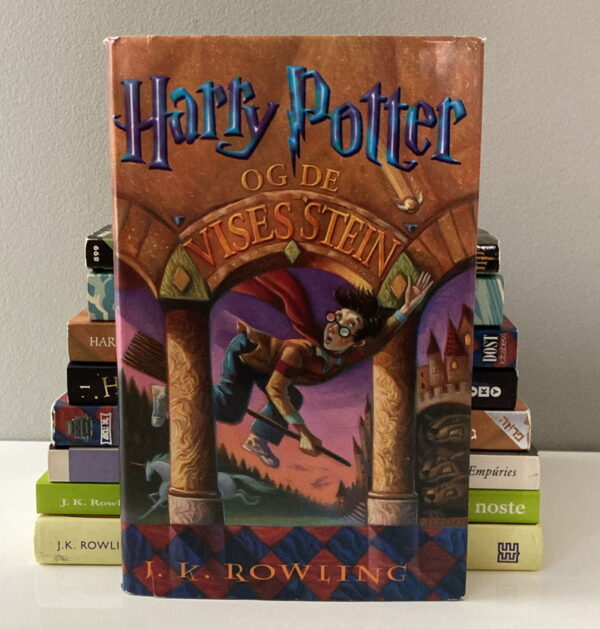

1. Norwegian: Harry Potter og de Vises Stein

What I love about this particular translation is how nicely it flows and how it creates so much humor of its own. Any gomp (non-magic person) who has gone through this translation has certainly enjoyed their visit to “Galtvort,” the magical school headed by Albus Humlesnurr and his deputy Minerva McSnurp! Be prepared for Gnav the Poltergeist, whose japes are as comical as the Norwegian game he’s named for.

Harry Potter og de Vises Stein, translated into Norwegian by Torstein Bugge Høverstad in 1998. Of course, coming up with clever names is not nearly enough for a good score. (Scots scored just 65.0 on the Spectrum!) The overall text flow and the humor of the translation are some of the most enjoyable I’ve seen so far. In many cases it’s even better than the original English! I can’t help but see Mrs. Dursley’s pucker-face when the narrator describes Dudleif, som var verdens aller nudeligste (“Dudley, who’s the most cutie wootie in the whole wide world”) on the opening page.

It’s no surprise that the Norwegian translation is so impressive. Its translator, Torstein Bugge Høverstad, is well-seasoned. Aside from Harry Potter, he has translated a tremendous amount of English-language fantasy and science fiction, including Lord of the Rings and Dune, as well as Charles Dickens (known for his vivid imagery and caricature) and Toni Morrison (whose illustrious writing style depends heavily on both syntax and word choice).

2. Maori: Hare Pota me te Whatu Manapou

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was translated into te reo Māori (a Polynesian language in New Zealand with somewhere between 50,000 and 200,000 speakers) at the initiative of the Kotahi Rau Pukapuka Trust. Its purpose was to engage people in Maori literature and culture using a familiar tale.

Hare Pota me te Whatu Manapou, translated into Maori by Leon Heketū Blake in 2020. It succeeded. I have yet to see a translation that has inserted as much local flavor as the Maori edition. The image you get in your head of the wizarding world changes entirely as you imagine, for example, potions brewing in a kōhua, a traditional Maori oven. The translator, Leon Heketū Blake, went so far as to research Maori incantations (karakia) to influence his translation, although I have not yet found how that bore fruit in the translation. To be determined…

The neologisms were brilliant: truly new but also comprehensible. “Fantastic Beasts” is kātuarehe (“cunning rascals”). “Transfiguration” is mata huri (“changing face”). “Vampire” is kaitoto (“eats blood”). My favorite is the translation of Slytherin, Nanakita, which plays on three words: nanakia (“treacherous, crafty”), naki (“glide”), and kita (“fastly”).

As I mentioned in a previous post, Maori is one of only a couple translations in the world that, to me, satisfactorily translates the first sentence of the novel. It did so by using an idiom of indignation native to Maori. Blake did a fantastic job translating the book into an enjoyable and Maori-oriented context. You can tell his heart was really into the mission of the Kotahi Rau Pukapuka Trust, and that motivation helped make it one of the top-scoring Harry Potter translations.

3. French: Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers

The French translation is so original that even the title was changed: Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers (“Harry Potter at the School of Sorcerers”)! That title is an indication of just how much freedom Jean-François Ménard had when he did this early translation in 1998. For whatever it’s worth to add, translators after 2000 were not so free.

Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers, translated into French by Jean-François Ménard in 1998. So much freedom in fact that he literally added to the story in some places.

When they first meet on the Hogwarts Express, Ron mentions his brother Percy is a prefect. Then he moves on immediately to describe his brother Fred and George.

But in the French edition, Harry interrupts:

– Préfet ? Qu’est-ce que c’est que ça ? demanda Harry.

– C’est un élève chargé de maintenir la discipline, répondit Ron. Une sorte de pion… Tu ne savais pas ça ?

– Je ne suis pas beaucoup sorti de chez moi, confessa Harry.

“Prefect? What is that?” asked Harry.

“It’s a student charged with maintaining discipline,” Ron responded. “A pawn of sorts… You haven’t heard of it?”

“I don’t get out much,” Harry confessed.

Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers (Jean-François Ménard)That exchange, explaining what a prefect is at the same time Harry’s learning all the other new wizarding world concepts, is entirely absent from the English edition, where a prefect is a typical part of the British schooling system. Instead, you’re left with the impression that prefecture is a feature unique to wizarding schools.

Overall, Ménard had quite a bit of fun wherever he could. This might even be the only translation where Hogwarts, Hogwarts, Hoggy Warty Hogwarts reads just as fun: Poudlard, Poudlard, Pou du Lard du Poudlard. His ability to maneuver as he wanted was key to making one of the best translations of the Harry Potter franchise.

4. Dutch: Harry Potter en de Steen der Wijzen (and Frisian: Harry Potter en de Stien fan ‘e Wizen)

The Harry Potter series was brought into Dutch by the same translator who did A Clockwork Orange… and you can tell! The Anthony Burgess novel is notorious for its frequent interspersion of Russian and Russian-derived words, whose meanings the reader must infer using context. That requires a skilled translator: the translator must construct an inferable context in the target language, or the reader will be lost.

Harry Potter en de Steen der Wijzen, translated into Dutch by Wiebe Buddingh’ in 1998. With such attention paid to individual words and phrases, it’s no wonder that Wiebe Buddingh’ opted to translate nearly every proper noun into a Dutch context. The first thing he considers when translating, according to this interview, are the names and puns. Hogwarts becomes Zweinsteins, Neville Longbottom becomes Marcel Lubbermans, and even Ron Weasley becomes Ron Wemel. Diagon Alley (a pun on “diagonally”) becomes Wegisweg (which can be interpreted as something like “Off to the Wayside”), a nice pun in Dutch playing off Weg (“Road,” used in street names) and tightened by alliteration. In the broader consideration of Harry Potter translations, the fact that Buddingh’ did not translate Newt Scamander might indicate the strong resolve of the Warner Bros. to market the Fantastic Beasts brand internationally, even before the film series was conceived. (Can anybody with a pre-2000 edition check for us whether the name was translated in early editions? EDIT: According to Harrison, the pre-2000 Dutch editions had Spiritus Salmander rather than Newt Scamander.)

An interesting cultural phenomenon is found in the names Albus Perkamentus and Draco Malfidus. Perkamentus is Latinized Dutch (from Dutch perkament, “parchment”) and Malfidus is just plain Latin (“Bad Faith”). Centuries ago, many elite families in Europe took on Latinized surnames and the presence of those Latinized surnames remains particularly pronounced among the Dutch today. This lends a sort of aristocratic feel to Albus Perkamentus and Draco Malfidus, which, frankly, is quite fitting for those characters and their families.

You probably noticed in the headline that I included the Frisian translation by Jetske Bilker. It scores nearly as high on the Spellman Spectrum as the the Dutch translation. But I chose not to treat it separately because it seems to have been translated into Frisian directly from Dutch (although it clearly consulted the English original as well). Thus the Frisian score is artificially high because it relies on many of the structural components that gave Dutch such a high score. Still, Bilker took a poetic approach of her own and does deserve credit for some of the score.

Harry Potter en de Stien fan ‘e Wizen, translated into Frisian by Jetske Bilker in 2007. 5. Luxembourgish: Den Harry Potter an den Alchimistesteen

This book received a surprisingly high score on the Spellman Spectrum for a translation I would consider more source-oriented and relatively literal. For those collectors who prefer translations that are unique but keep the original names, this might be the high-scoring book for you! It’s easy to see why it scored so high, though, especially considering how one-of-a-kind written Luxembourgish can be.

Den Harry Potter an den Alchimistesteen, translated into Luxembourgish by Florence Berg in 2019. The translator, Florence Berg, made some very clever interpretations. We see that immediately in the title of both the first book (Alchimistesteen, “Alchemist’s Stone,” referring directly to Nicolas Flamel) as well as the second (Salazar säi Sall, “Salazar’s Hall,” referring to the Chamber of Secrets). Another fun title is that of the Beginner’s Guide to Transfiguration, which becomes the Abécédaire fir Verwandlung (“The ABC’s of Transfiguration”).

Concluding thoughts

There you have it, the top 5 (or 6?) translations of the first 30-some editions rated on the Spellman Spectrum: Norwegian, Maori, French, Dutch (and Frisian), and Luxembourgish!

Have you had the chance to read any of these? If so, leave a comment with your thoughts about the translation and what aspect you enjoyed the most!

-

What’s so interesting about Harry Potter in translation?

In today’s post, I’m going to demonstrate what makes the translation of Harry Potter such an interesting phenomenon for so many of us. By way of example, I’ll focus particularly on the concept of a “Hufflepuff” in the original English Harry Potter and compare it to the Danish Harry Potter. Then I’ll narrow in on “troll” as a culture-specific element that requires replacement in languages like Turkish in order to be fully comprehensible to its readers. Finally, I’ll discuss the translation of humor across languages, highlighting Oliver Wood and his name as an example.

But first, let’s talk briefly about the nature of language.

Language reflects a lot about the world around us. It reveals something about its utterer, and the people being uttered to. Communication involves making choices, both conscious and unconscious, that rely on the social norms of a language community. And because people appeal to those social norms when they communicate, how people use language to convey thoughts and ideas tells us a lot about the people they’re speaking to or writing for.

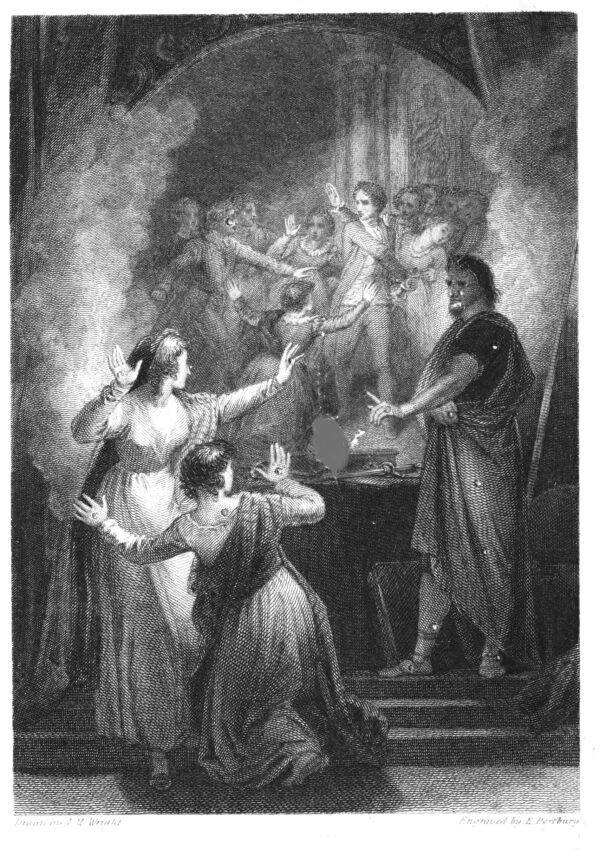

“The Magic Mirror” by J.M. Wright, 1827. Sketch illustrating “My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror” by Sir Walter Scott. The translation of a familiar tale offers a window into other worlds—not magical ones, but living, breathing communities across the world today. Children (and adults) of more than 80 language communities sit down and enjoy Harry Potter in their own tongue, in a way that speaks to them.

Many other novels and works have been translated into just as many languages, or even more. But what makes Harry Potter so interesting is its clever world-building. Not only does the series contain innumerable neologisms—new concepts and objects—but its wizarding world is built on a Muggle world familiar to the reader. Translators not only must convey the intended meaning of the author, but they must also connect the novel’s magic with the everyday world of their language community.

Creating a Wizarding World through Language: How do you fluff enough of Hufflepuff?

That’s not a simple task and it requires a lot of wit. You may have never considered how exactly J.K. Rowling created the image of a typical Hufflepuff in your head early on in the Harry Potter series. The word Hufflepuff itself calls to mind the phrase “huff and puff,” as in the Big Bad Wolf’s great labor to blow the Three Little Pigs’ house down. As soon as we’re introduced to the word “Hufflepuff,” this “huff and puff” reference is immediately but subtly reinforced by the Sorting Hat’s song: “True patient Hufflepuffs are true and unafraid of toil.”

The association of “Hufflepuff” with both “huff and puff” and “toil” is an important first step in the world-building process that creates the concept of a Hufflepuff. Translators cannot reproduce this English-specific reference and must replace it with a new process in order to start building the concept of “Hufflepuff” in a smooth and enjoyable manner.

Let’s look at how Danish translates the Hufflepuff portion of the Sorting Hat’s song:

I Hufflepuff du kan få plads,

hvis du er en stræber,

loyal og god, og venners ven

er nok, hvad huset kræverYou can fit in Hufflepuff,

Harry Potter og de Vises Sten (Hanna Lützen)

if you exert yourself,

loyal and good, and a friend of friends

is probably what the house requiresStudents of Roman Jakobson will appreciate the heavy use of alliteration and the rhyming of stræber (“someone who exerts themselves”) with kræver (“requires”). Instead of relying, as in English, on the association of “Hufflepuff” with “huff and puff,” what stands out to the Danish reader (and what remains their initial impression of Hufflepuff) is that Hufflepuffs are venners ven (“a friend of friends”) and that stræber is an essential [kræver] quality of being a Hufflepuff.

Translation Trolls and Other Troublesome Travails

Let’s take another element from Harry Potter and explain why its translation is interesting.

English speakers often take for granted how very British the Harry Potter series is, entrenched in centuries of English-language literature (as well as the Celtic, Nordic, French, and Latin literatures that greatly enriched the English imagination). Translators across the world have grappled with how they should translate concepts as simple as a “troll”: children in their countries would have never heard of such a creature!

That’s presumably why Ülkü Tamer, the translator of the second Turkish translation of Philosopher’s Stone, opted to change the troll in the dungeon to an ifrit, a sort of mischievous genie which is well-known to any Middle Easterner but is quite different from a troll.

“Hasan of Bassorah” by Albert Letchford, 1897. Illustration of a scene from One Thousand and One Arabian Nights depicting some ten ifrits emerging from the earth. Lost in Translation: Getting the punchline

And accompanying any witty world-building journey comes a whimsicality in the author’s style, simply in how a tale is turned. Take for instance that unforgettable introduction of Oliver Wood:

“Excuse me, Professor Flitwick, could I borrow Wood for a moment?”

Wood? thought Harry, bewildered; was Wood a cane she was going to use on him?

“Potter, this is Oliver Wood.”

This translated really well into French and Dutch, where “Wood” conveniently translated into a common surname as in English:

– Excusez-moi, dit-elle au professeur qui donnait son cours dans la salle . . . Puis-je vous emprunter du bois [some wood] quelques instants ?

Du bois [some wood] ? Avait-elle l’intention de lui donner des coups de bâton? se demanda Harry, déconcerté.

– Potter, je vous présente Olivier Dubois.

Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers (Jean-François Ménard, French)‘Neemt u me niet kwalijk, professor Banning, maar mag ik Plank even?’

Plank? dacht Harry verbijsterd. Bedoelde ze een stuk hout, om hem mee af te ranselen?

‘Potter, dit is Olivier Plank.

Harry Potter en de Steen der Wijzen (Wiebe Buddingh’, Dutch)Other languages were not so lucky. Some translations, like Bosnian, even use a footnote to explain to the reader that “Wood” is the English word for wood! (This in turn, by the way, reinforces for the Bosnian reader the notion that Harry is a foreigner who speaks a foreign language—already quite a different experience from the Harry we experience as English speakers!)

Footnote in Harry Potter i Kamen Mudrosti, the Bosnian translation of Philosopher’s Stone by Mirjana Evtov. As you can see, Harry Potter has a lot to offer for anybody interested in language and translation. You just have to know where to look and what to look for.

So I invite you all to join me in my study of this magical tale in the many languages of the world, and together we’ll uncover all sorts of interesting tidbits about people and their communities around the globe!

-

Why the fascination for Harry Potter in translation?

In today’s post, I’m going to demonstrate what makes the translation of Harry Potter such an interesting phenomenon for so many of us. By way of example, I’ll focus particularly on the literary production of the concept of a “Hufflepuff” in the original English Harry Potter and compare it to the Danish Harry Potter. Then I’ll narrow in on “troll” as a culture-specific element that requires replacement in languages like Turkish in order to be fully comprehensible to its readers. Finally, I’ll discuss the translation of humor across languages, highlighting Oliver Wood and his name as an example.

But first, let’s talk briefly about the nature of language.

Language reflects a lot about the world around us. It reveals something about its utterer, and the people being uttered to. Communication involves making choices, both conscious and unconscious, that rely on the social norms of a language community. And because people appeal to those social norms when they communicate, how people use language to convey thoughts and ideas tells us a lot about the people they’re speaking to or writing for.

“The Magic Mirror” by J.M. Wright, 1827. Sketch illustrating “My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror” by Sir Walter Scott. The translation of a familiar tale offers a window into other worlds—not magical ones, but living, breathing communities across the world today. Children (and adults) of more than 80 language communities sit down and enjoy Harry Potter in their own tongue, in a way that speaks to them.

Many other novels and works have been translated into just as many languages, or even more. But what makes Harry Potter so interesting is its clever world-building. Not only does the series contain innumerable neologisms—new concepts and objects—but its wizarding world is built on a Muggle world familiar to the reader. Translators not only must convey the intended meaning of the author, but they must also connect the novel’s magic with the everyday world of the language community.

Creating a Wizarding World through Language: How do you fluff enough of Hufflepuff?

That’s not a simple task and it requires a lot of wit. You may have never considered how exactly J.K. Rowling created the image of a typical Hufflepuff in your head early on in the Harry Potter series. The word Hufflepuff itself calls to mind the phrase “huff and puff,” as in the Big Bad Wolf’s great labor to blow the Three Little Pigs’ house down. As soon as we’re introduced to the word “Hufflepuff,” this “huff and puff” reference is immediately but subtly reinforced by the Sorting Hat’s song: “True patient Hufflepuffs are true and unafraid of toil.”

The association of “Hufflepuff” with both “huff and puff” and “toil” is an important first step in the world-building process that creates the concept of a Hufflepuff. Translators cannot reproduce this English-specific reference and must replace it with a new process in order to start building the concept of “Hufflepuff” in a smooth and enjoyable manner.

Let’s look at how Danish translates the Hufflepuff portion of the Sorting Hat’s song:

I Hufflepuff du kan få plads,

hvis du er en stræber,

loyal og god, og venners ven

er nok, hvad huset kræverYou can fit in Hufflepuff,

Harry Potter og de Vises Sten (Hanna Lützen)

if you exert yourself,

loyal and good, and a friend of friends

is probably what the house requiresStudents of Roman Jakobson will appreciate the heavy use of alliteration and the rhyming of stræber (“someone who exerts themselves”) with kræver (“requires”). Instead of relying, as in English, on the association of “Hufflepuff” with “huff and puff,” what stands out to the Danish reader (and remains their initial impression of Hufflepuff) is that Hufflepuffs are venners ven (“a friend of friends”) and that stræber is an essential [kræver] quality of being a Hufflepuff.

Translation Trolls and Other Troublesome Travails

Let’s take another element from Harry Potter and explain why its translation is interesting.

English speakers often take for granted how very British the Harry Potter series is, entrenched in centuries of English-language literature (as well as the Celtic, Nordic, French, and Latin literatures that greatly enriched the English imagination). Translators across the world have grappled with how they should translate concepts as simple as a “troll”: children in their countries would have never heard of such a creature!

That’s presumably why Ülkü Tamer, the translator of the second Turkish translation of Philosopher’s Stone, opted to change the troll in the dungeon to an ifrit, a sort of mischievous genie which is well-known to any Middle Easterner but is quite different from a troll.

“Hasan of Bassorah” by Albert Letchford, 1897. Illustration of a scene from One Thousand and One Arabian Nights depicting some ten ifrits emerging from the earth. Lost in Translation: Getting the punchline

And accompanying any witty worldbuilding journey comes a whimsicality in the author’s style, simply in how a tale is turned. Take for instance that unforgettable introduction of Oliver Wood:

“Excuse me, Professor Flitwick, could I borrow Wood for a moment?”

Wood? thought Harry, bewildered; was Wood a cane she was going to use on him?

“Potter, this is Oliver Wood.”

This translated really well into French and Dutch, where “Wood” conveniently translated into a common surname as in English:

– Excusez-moi, dit-elle au professeur qui donnait son cours dans la salle . . . Puis-je vous emprunter du bois [some wood] quelques instants ?

Du bois [some wood] ? Avait-elle l’intention de lui donner des coups de bâton? se demanda Harry, déconcerté.

– Potter, je vous présente Olivier Dubois.

Harry Potter à l’école des sorciers (Jean-François Ménard, French)‘Neemt u me niet kwalijk, professor Banning, maar mag ik Plank even?’

Plank? dacht Harry verbijsterd. Bedoelde ze een stuk hout, om hem mee af te ranselen?

‘Potter, dit is Olivier Plank.

Harry Potter en de Steen der Wijzen (Wiebe Buddingh’, Dutch)Other languages were not so lucky. Some translations, like Bosnian, even use a footnote to explain to the reader that “Wood” is the English word for wood! (This in turn, by the way, reinforces for the Bosnian reader the notion that Harry is a foreigner who speaks a foreign language—already quite a different experience from the Harry we experience as English speakers!)

Footnote in Harry Potter i Kamen Mudrosti, the Bosnian translation of Philosopher’s Stone by Mirjana Evtov. As you can see, Harry Potter has a lot to offer for anybody interested in language and translation. You just have to know where to look and what to look for.

So I invite you all to join me in my study of this magical tale in the many languages of the world, and together we’ll uncover all sorts of interesting tidbits about people and their communities around the globe!

-

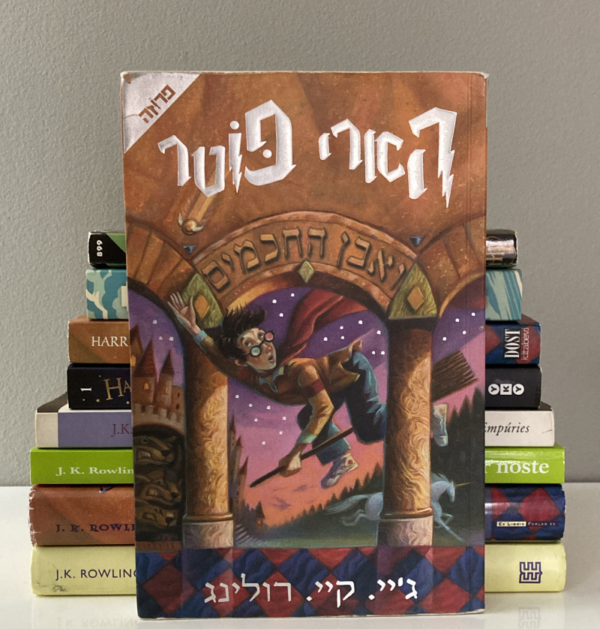

Harry Potter in Hebrew: how good is the translation?

On some level, Hebrew is an interesting choice for a translation of the Harry Potter series. The 20th-century revival of the language, which was in minimal use for some two thousand years, was a bit on the controversial side. For centuries it had been a holy language, reserved for the Tanakh, for prayer, and for religious discussion, but not for everyday tasks. Early on, some of the Jews in the Holy Land who were eager to establish a Jewish state advocated Yiddish as the common language of Israel—Hebrew was simply too holy. Ultimately, Hebrew won out. And by the turn of the century, even books about wizards and witches (Harry Potter!) ended up published in the language.

Another reason why translation into Hebrew is interesting is because the ancient language’s literary culture is really very young. There isn’t a ton of history of the language being used to express complex imagery outside of religious literature, and intertextuality is relatively restricted to the Bible and other well-known but extrascriptural religious texts. On top of that, for much of the 20th century the audience for Hebrew literature was dominated by non-native speakers who had picked up the language sometime after early childhood, and so the market for literature using intricate literary devices was limited as it catered to those non-native speakers.