Home

-

Three versions of Harry Potter in Arabic: read our post over at Potterglot!

Genies. Ghouls. Alchemy. And Percy staging a coup? These are all features you’ll find in the Arabic editions of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

When we discovered last month that there are three Arabic versions of the early Harry Potter series, Potterglot and I worked for weeks piecing the puzzle together about what exactly was going on. The changes by the publisher appear to have been done silently, with no trace of announcement or advertisement about updates they were making to the translation. Special shout out to everyone who contributed to our research by sending screenshots of their own Arabic copies and even sending clips from Arabic audiobooks!

Because I have good knowledge of Arabic, I had the pleasure of writing as a guest on Potterglot’s website about the textual differences I had found in the three versions. Although Potter of Babble seeks to help collectors appreciate the language and text that they possess, Potterglot provides indispensable information to help collectors, well… collect! One of the most useful resources he’s compiled over the years is The List, a treasury of details on foreign editions around the world that come in handy when you’re hunting down a translation that’s impossible to find. The site has been an invaluable resource for collectors for years, and my article sought to help collectors choose which of the three Arabic editions they might want to collect.

So it seemed only fitting that that information be added to Potterglot’s library, rather than ours at Potter of Babble.

But if you’ve come to this post hoping to see dozens of text samples or an analysis of the strategies used in the Arabic translation, don’t fret! You can read it here on Potterglot and, while you’re at it, check out his own investigation into the publication details in case you want to search out a copy of your own.

Cheers!

-

5 Christmas Comfort Foods in Harry Potter from Around the World

Have you ever thought about just how much food is in the Harry Potter books? There’s a ton, from baked potatoes to lemon sherbets to Fizzing Whizzbees™. It is an important literary device, used to define settings and build characters.

In translation, changes in food items are some of the most visible. One reason is because food is very culture-specific. Kids reading the series in another language may have no idea what English dishes like “shepherd’s pie” and “black pudding” are. In some cultures, parents would be shocked that their kids are reading about some foods. (Think “bacon,” which to Muslims is repulsive. Translations in Muslim countries tend to translate the word as simply “meat.”)

From a literary standpoint, the foods should evoke an emotional connection from the readers in the target culture. When they read about Hogwarts feasts, they should feel like it’s a comfortable, home-cooked meal, not a visit to a restaurant for a foreign cuisine. When they read about maggoty haggis at Nearly Headless Nick’s deathday party, they should feel repulsed knowing that haggis is already a bit festering even without the maggots. For a translator, it’s very hard to keep unfamiliar food items on the menu. And also one of the easiest things to change. (So easy in fact, that a translator may not even realize they are changing the food: when Polish kids read about Harry sinking his teeth into a kiełbasa [the Polish word for “sausage”], they’re probably not thinking of the same kind of sausage that English kids typically eat.)

When Harry and Ron stay behind for the Christmas holidays in Philosopher’s Stone, they roast crumpets and marshmallows by the fire. Like chestnuts (which are mentioned in the Italian translation), they’re popular holiday fireplace foods. So what were some of the foods they were changed to in translation? Here are just five of the foods found in their place:

Slăninută (Romania)

At first sight it looks like tiramisu, but slănină is savory, not sweet. It’s a cut of pork fat, seasoned for consumption as a delicacy in much of Eastern Europe. Not a bad idea for your next charcuterie!

Petulla (Albania)

These doughnuts are a popular snack for Eid al-Fitr in Albania (and on Christmas for Albanian Christians). It’s most commonly eaten with a salty cheese or honey, but jams, chocolate, yogurt, or even ketchup are also common.

Melcocha (Spain and Latin America)

Melcochas are a type of hard candy made from sugar and popular during the Christmas season. The exact recipe and form of melcochas varies by country and region, and it often includes vanilla, cocoa, and/or lemon flavoring.

Qatlima (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region)

This is a flaky, layered bread packed with oil, butter, or animal fat, and sometimes stuffed with meat, cheese, nuts, or veggies. It’s popular throughout Central Asia, though more commonly known as qatlama. Pictured is a variation from Uzbekistan, quite similar to what you’d find in Uyghur cuisine.

Cocon / Coca (Southern France and Catalonia)

Known as “Cocon” to Occitania in southern France and “Coca” to Catalonia in eastern Spain, this baked good can be either sweet or savory. One popular variation along the Mediterranean can even be topped with sardines or anchovies! A Christmas variation (pictured), topped with a generous amount of powdered sugar, looks as snowy as the season.

-

Spellman Spectrum v1.1

Potter of Babble has been running a bit slowly the past few months. One of the reasons is because the original Spellman Spectrum got out of whack. When it was first designed, it was making use of only a few dozen data points per translation. The amount of data points has since multiplied, though, and now they number in the triple digits. The model’s calculation became lopsided and no longer seemed to reflect whether a translation was more rigid or loose, as the scale was intended to do.

So we’ve spent some time working on modeling a Spellman Spectrum v2.0. That model aims to be more firmly rooted in concepts of data science, but conceptualizing a workable model has taken much longer than anticipated.

As a stopgap to keep things going, I’ve tinkered with the original model, which I’m calling v1.1. Like the original model, it relies largely on an evaluation of various weighted data points. Here’s a bit more about who model v1.1 works:

- It’s no longer dependent on the amount of data points. Whether a translation is 10% evaluated or 90% evaluated, the scale should work. Nor should the number of data points matter, whether 50 data points or 1500.

- It’s bound to a sigmoidal function. A basic mechanic used in supervised machine learning, sigmoidal functions are a great tool in tailoring models to fit shifting data sets, as is the case while building model v2.0. It also creates greater distinction in the middle of the scale, where most of the translations lie. A book that previously rated 45 might now be closer to 40, while a book that previously rated 55 might be closer to 65. This leads to a greater spread throughout the scale.

- It now uses aggregate weighting. All data points in a category are totaled before weighting is applied. This allows us to collect as much data as possible in a weighted category even if such a representative amount is unavailable for another weighted category. That, in turn, means a more finely tuned score.

- It accounts for having too little data in a high-ranking category. At the time of this post, most of the evaluated translations have 5 or fewer data points in the highest-ranking category, which is too small to be considered representative. The scale automatically adjusts the weighting of a category if it falls below a representative threshold.

- It changes how some translations rank. The Maori translation was previously the top-rated, in part because of how much the translation nativizes the high number of low-ranking data points. With the weighting mechanisms adjusted, Maori still ranks very high, but below a few other translations. Meanwhile, while the Brazilian Portuguese rating stayed virtually unchanged at 56.3, the Lusitanian Portuguese rating declined from 57 to 40.

The model still has its problems, which is why the work doesn’t stop at v1.1. One of the drawbacks of this version is that the highest-rated translations on the scale do not have a good spread. French and Norwegian rate 96.6 and 99.4, respectively. Not only does that quantitative proximity mask the qualitative differences between them, but their scores’ closeness to 100 misleadingly suggests that you can’t get much more creative than the Norwegian translation. This is a side effect of the transformations made to the sigmoidal function, which sacrificed the differentiations on the upper end of the scale for greater differentiation in the middle.

On the other hand, knowing, in a superlative sense, that French and Norwegian are among the most innovative translations is enough for most Harry Potter translation enthusiasts. It’s in the middle of the scale where the differences between translations is most interesting.

-

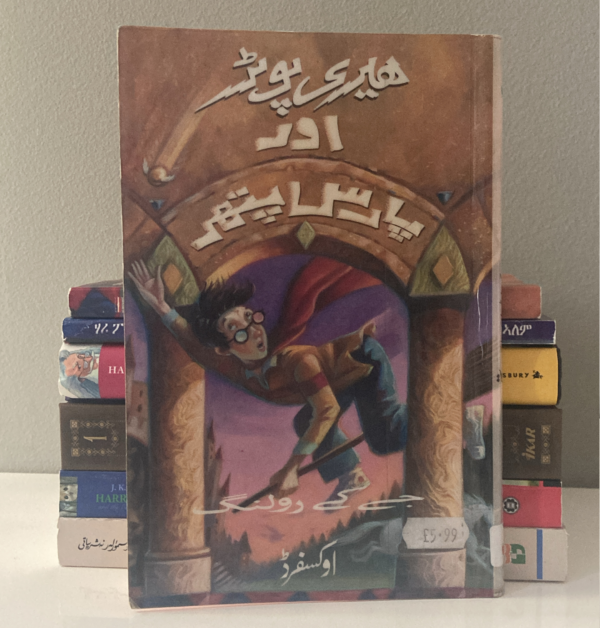

The two Urdu translations of Harry Potter

One of the more difficult languages to find Harry Potter in these days is Urdu, a language mutually intelligible with Hindi that’s spoken in India, Pakistan, and even the United Arab Emirates. The original translation was done by Darakshanda Asghar Khokhar, apparently a housewife in Pakistan who wanted to make the immensely popular English-language novel available in Urdu. It’s no longer in print—possibly because English is widely understood in Pakistan, where Urdu is spoken by only 8% of the population. In other countries where people commonly read in English, like India or the Philippines, many of their Harry Potter translations have also fallen out of print.

A second translation, by Moazzam Javed Bokhari, has become more readily available in recent years. And while collectors tend to prefer the original Khokhar translation, the question has come up whether original truly is better.

So I’ve decided to visit that question in today’s post. Before beginning, I’d like to preface with a disclaimer. I have a lot of exposure to spoken Hindi, and I know Arabic, and this has helped me take a look through these two translations. But I don’t speak Urdu myself and its script is somewhat difficult from an Arabic standpoint, so I’m prone to make mistakes. Moreover, like Arabic, Urdu writing often omits vowels and I’ve had to fill in with some guesswork. So if you’re an Urdu speaker, I welcome your input and apologize in advance for any errors that have slipped through the cracks.

Both are source-oriented. And use English in Urdu script?

Now, what’s interesting in comparing the Khokhar and Bokhari translations is how similar they are in their fundamental approach. They’re both source-oriented and use a surprising amount of transliteration of English. The Hogwarts admission letter to Harry, for example, is addressed in both translations to “Mr. H Potter” (misṭar aich poṭar). For those aware of the history of Pakistan and India, you’ll know that the extensive use of English in these two translations reflects the lasting impact of the British colonial era in South Asia.

The Khokhar translation also leaves the name of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry untranslated, transliterating it instead: hogwarṭs askool aaf wizarḍree ainḍ wich kraafṭ. Indeed many private schools in Pakistan similarly retain English names. More striking, though, are the lack of translation for terms like “Sorting Hat” (sorṭing haiṭ), “Seeker” (seekar), and “First Years” (first ayeerz). Even the book titles on Harry’s school list are given in English (e.g., fainṭasṭik beesṭs ainḍ wayir ṭoo fayinḍ daim). Following the experience of many Urdu speakers (in both Pakistan and the United Kingdom), Hogwarts in Khokhar’s translation is very clearly an English-speaking school where English is the language of instruction and school activities are conducted in English as well.

Food cooking in a karahi, a flat-bottom style of wok common in South Asia and the word used by Moazzam Javed Bokhari in his translation of “cauldron” in Harry Potter aur Paras Pathar. Bokhari translates a bit more into Urdu. Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is hogwart skūl beraa’e jaawogaree opar asraar ‘uloom (“Hogwarts School for Witchcraft and Occult Sciences”). Vampire is translated as khoon ashaam bhoot, a term apparently imported from Persian literature. Cauldron is translated as kaṛahee, a flat-bottom style of wok specific to South Asia. Even Dumbledore’s favorite sweet is transformed into a sekanjabin, a refreshing honey-vinegar drink that’s also Persian in origin. Meanwhile, Khokhar translates goblin and troll into terms familiar to Urdu (boona, “dwarf,” and dev, a type of horned ogre), while Bokhari retains the English words for those creatures.

Illustration of a dev being killed by Rustam, the hero of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the Persian national epic. Both translations retain most of the proper nouns of the English, although Khokhar’s transliterations are much more simple. Bokhari is a bit more daring: wizarding world terms are more likely to be translated, like “Remembrall” (yaaddaashtee gaind), although the meticulous transliteration of names like Quirrell can lead to a mouth full (kyooryeel).

Khokhar is too plain; Bokhari is too literary

The Khokhar translation gets a bit overly simplistic or explanatory in certain places. Instead of translating “poltergeist” in some way, Peeves is glossed as a spirit that appears upon summoning. Sure, that’s an attempt to differentiate Peeves from other ghosts. But it doesn’t really capture either Peeves’ character or the meaning of “poltergeist.”

In a scene where, in English, Harry and Ron are roasting bread, English muffins, and marshmallows over the fireplace, Khokhar simply says they were eating really fun stuff. And when Snape gives his poetic introduction to Potions class—it’s a bit less inspired in Khokhar’s Urdu: I hope you can truly appreciate the beauty of this art. A cauldron boiling ever so slowly and the florescent smoke exuding from it. His voice is monotonous and droning by comparison.

Bokhari’s translation seems to have a more natural flow. But at times it seems awkwardly literary where Rowling had intended something more colloquial. Compare Khokhar and Bokhari on Peeves’ tease when he discovers Harry and friends out past midnight:

English original: “Wandering around at midnight, Ickle Firsties? Tut, tut, tut. Naughty, naughty, you’ll get caughty!”

Adhee raat ko awaarah gardee. Nanhe First Year baby, tut tut. Sharaartee sharaartee pagre jawu ge. Sharaartee.

“Midnight wanderers. Little First Year babies, tut tut. Naughty, naughty, you’ll be caught. Naughty.”

Harry Potter aur Paras Pathar by Darakshanda Asghar KhokharAnd here’s Bokhari’s Urdu, which has pleasant meter and rhyme, including internal rhyme, but is just too intricate and long for Peeves’ cutting jest:

Adhee raat ko baahar ghoom rahe ho,

saal awwal ke nanhe mane bacho!

He he he. Qavaaneen kee khalaaf warzee

pagṛe jaane se ḍaṛte bahee ho.“Out walking around at midnight, little first year children! He he he. Breaking the rules, scared of getting caught.”

Harry Potter aur Paras Pathar by Moazzam Javed BokhariAnd when Peeves is tattling on Harry and friends for being out past midnight, he demands Filch ask “Would you be so kind to tell me where they went?” rather than “Please tell me where they went.” In a similar vein, even Hagrid uses a more literary command when asking Harry in a letter to send a response with Hedwig than something more fitting for Hagrid.

Khokhar better captures J. K. Rowling’s intent

It’s perhaps Bokhari’s attempt to capture a more formal Urdu reading that also leads him astray when it comes to certain subtleties. When Harry approaches Uncle Vernon about the train to Hogwarts, Uncle Vernon reacts: “Funny way to get to a wizards’ school, the train. Magic carpets all got punctures, have they?” The colloquial phrasing in this line in English is designed to highlight how funny it is to get to a wizard’s school by train. “The train is a funny way to get to a wizard’s school” would be more grammatically sound, but that standardized phrasing would focalize the sentence around the train. Rowling deliberately chose to buck what’s grammatically appropriate because the more colloquial arrangement better captures Vernon’s attitude.

Khokhar’s translation catches this subtlety: ʿajeeb ṭareeqah he, jaadoogaroon ke askool pahunchane ka. rail gaaṛee se. “Weird way, that is, to get to a wizards’ school. By train.”

Bokhari’s translation changes the focalization to the train: rail gaaṛee se bahee koee jaadoogaroon ke skool meen jaataa he? baṛaa ʿajeeb ṭareeqah he. “Train, who goes to a wizards’ school by that? It’s a very weird way.”

While some readers wouldn’t be bothered by such subtleties, the Khokhar translation is simply more astute in that regard.

Concluding thoughts

Overall, the translations are largely similar in approach. The Khokhar translation is a bit simpler, while the Bokhari translation is a tad more elegant. For a more easy landing into Urdu, we’d recommend Khokhar. For something a little more literary, Bokhari is probably the better bet. This is reflected in the Spellman Spectrum rating, which rates Khokhar’s translation at 34.5 (indicating an easier read for language learners) and Bokhari’s at 53.4 (indicating a read that jibes somewhat better with Urdu literary standards). But if one is more accessible to you—whether you have Khokhar in your local library or Bokhari is easier to find online—there’s not much lost in being “stuck” with one or the other!

-

Harry Potter wizard swears in different languages: Part 1

A very fun part of building a wizarding world in the Harry Potter series is constructing sorcery slang. Here’s a look at a few of the cusswords that make an appearance in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone around the world:

German: Schluckende Wasserspeier! “Swallowing Water-Spitter.” Water-Spitter is what the Germans call a Gargoyle because, well, they spit water. But what happens when a water spitter swallows instead? A topsy turvy curse that rolls off the tongue!

Hindi: तूफान की आँख (Tufan ki ankh!) “Eye of the Storm!” This phrase is a double entendre—tufan is the Hindi word for Quaffle.

Norwegian: Men gryntende gomper! “Grunting Muggles!” Another nice use of a term specific to Harry Potter. Gomper is the Norwegian translation for Muggles.

Dutch: Alle slangen en serpenten op een stokkie! “Every snake and serpent on a stick!” This nice, long exclamation goes great when stubbing your toe. Or getting through your Skele-Gro.

Faroese: Trøll og tussar! “Trolls and giants!” Short and sweet. Alliterative t‘s. And pairing near-synonyms of magical creatures. This Faroese swear really hits the mark!

Hebrew: בשם השדים שבשמים (Bashem hash’dim sh’beshamayim!) “In the name of the spirits up in heaven!” Some nice repetition of sh‘s and m‘s and even b‘s in this one. Not quite a tongue-twister, but pretty poetic.

-

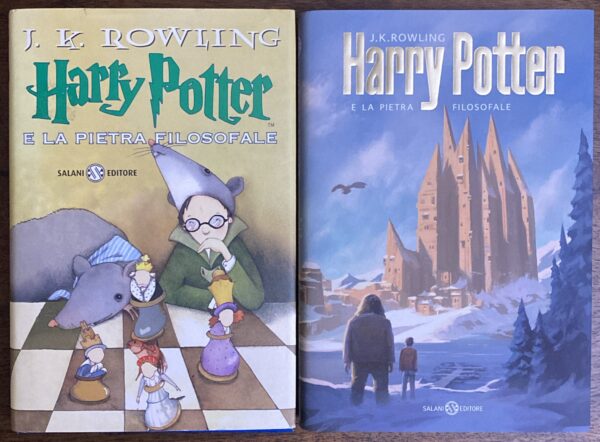

A brief look at the revisions to Harry Potter in Italian

Lately I’ve been taking a look through the Italian translation of Philosopher’s Stone, first published in 1998 but extensively revised and edited in 2011. The translation by Marina Astrologo is a classic pre-movie translation and quite well done. But the translation was done as a stand-alone before Chamber of Secrets was even published. Astrologo could not foresee how the rest of the Harry Potter saga would play out before deciding how to set the proper tone with words like goblin and Neville Longbottom.

So after the series had been fully published, the Italian publisher commissioned a revision (by Stefano Bartezzaghi) of the books to sort of standardize the language throughout the series. This was met with backlash and annoyance among those Italian readers who had to relearn the names of their favorite characters, but it also earned a good amount of defenders. You can read a bit more about the rationale behind the revision over at Potterglot.

For now, I just want to give you a little illustration of the sorts of changes that were made. From all I’ve looked at so far, there’s probably no more representative sample than the Oliver Wood pun.

In the original Italian translation from 1998, we have:

“Mi scusi, professor Vitious, mi presta Baston per un attimo?” Baston? pensò Harry allibito; forse la McGranitt aveva intenzione di picchiarlo?

“Excuse me, Professor Vitious, would you lend me Baston [Baton] for a moment?” Baston [Baton]? thought Harry shocked; maybe McGranitt was intending to beat him?

The revised Italian translation makes quite a few changes:

“Mi scusi, professor Flitwick, mi presta il suo Wood per un attimo?” ‘Il suo Wood?’ pensò Harry confuso; sperò che la situazione non stesse prendendo una brutta piega.

“Excuse me, Professor Flitwick, would you lend me your Wood for a moment?” ‘Your Wood?’ thought Harry confused; he hoped that the situation was not taking a turn for the worst.

Here are a few observations:

- The names have been changed in favor of Warner Bros. trademarks. Vitious, Baston, and McGranitt have all reverted to Flitwick, Wood, and McGonagall (and McGonagall was also removed from this excerpt altogether).

- The pun was sacrificed in favor of restoring ‘Wood.’ Baston, which is a genuine surname just like Wood, means “baton” in Italian and lent itself well to the pun.

- The adjustment is broad and thorough. It’s clear that the backbone of Astrologo’s translation is intact—even though only 10 of the words remained the same. The entire excerpt is recast in order to accommodate the change from ‘Baston’ to ‘Wood.’

- The language remains engaging. Although the original pun is no longer there, the new presentation is hardly stilted. An engaging workaround was conceived. This follows a trend throughout the revision: not only were proper nouns and magical concepts standardized for a better flow, but the language was also made more smooth.

So what judgments can be gleaned from this example? I think that’s largely open to your preferences. On the one hand, the revised translation of Philosopher’s Stone in loses some of the pizzazz and originality of the older translation. But it jives better in the broader context of Harry Potter, both in terms of the Italian translation of the series and in terms of the global franchise, without losing the creativity and flow of the Italian text.

-

“P for Prefect!” Molly Weasley gets in on the joke!

Harry Potter plays on English at every turn, and often in the most subtle of ways. When Christmas rolls around in Philosopher’s Stone, Molly Weasley gifts Percy a knitted sweater with a big ol’ “P” for Percy. But Fred jokea that the “P” actually stands for “Prefect,” carrying on a year-long tease of Percy taking his prefecture too seriously. Of course, this tease requires Percy’s name and the word “prefect” to begin with the same letter as his name.

So what about translations that don’t translate prefect as prefect? After all, the position of Prefect is a very British thing to have in a school. Some translations even feel the need to explain or footnote what exactly Percy’s role is because the target culture has no equivalent concept.

One obvious solution is to change Percy’s name in the target language to match the translation of prefect. But so far I have not come across any translation that makes any significant changes to Percy’s name. (And I’m unlikely to find any: since the expansion of the Harry Potter franchise after 2000, proper nouns have largely remained unchanged across translations.)

So let’s take a look at three different ways this translation problem is resolved.

Ditching the “P”: German, Icelandic, Finnish, and Turkish

The most common strategy translators use (aside from just keeping the word prefect) is ditching the “P” on the sweater. This ends up bringing Molly into the tension in these translations, because she chooses to stitch the letter for prefect over the letter for Percy:

German (Klaus Fritz): “V für Vertrauensschüler! Zieh ihn an, Percy…”

Icelandic (Helga Haraldsdóttir): “U fyrir umsjónarmanninn! Klæddu þig í hana, Percy.”

In these translations, Percy is the only one gifted a sweater with a letter that is different from the first letter of his name. Molly gave a sweater knitted with “R” to Ron, “H” to Harry, “F” to Fred, and “G” to George.

This is a significant alteration by the translations because, in English, there is no reason to think Molly intended any sort of double entendre with her P-stitched sweater. In these translations, she is acknowledging that Percy’s identity is wrapped up in being a prefect, and accommodates his enthusiasm—while giving Fred and George great fodder for teasing.

Interestingly, Jaana Kapari-Jatta’s Finnish translation changes the letter but leaves the reader to infer what it stands for. “Sinun puserossassi on V! Pue se päällesi, Percy…” (The V stands for valvojaoppilas, the Finnish equivalent of a prefect.)

Mustafa Bayındır’s Turkish also changes the letter to fit Percy’s position as “class president” (sının başkanı): “Sınıf başkanının S‘si! Giysene, Percy…”

Preserving the P: Turkish (again), Danish, Maori, and Malay

The later Turkish translation by Ülkü Tamer uses a different strategy, choosing a phrase that allows Molly to keep the “P”: “P var! Herhalde Parlak Öğrenci anlamındadır! Hadi, Percy, giy şunu.” This is interesting because, to achieve this, Tamer actually removes the concept of a prefect from the tease altogether: “There’s an S! It probably means Star Student! Come on, Percy, put it on.” “Star Student” isn’t meant as a replacement for prefect here; Percy is still the class president (sının başkanı) in this translation.

Hanna Lützen’s Danish translation does something similar. While Percy holds the position of vejleder (mentor), Fred teases: “Vejlederen har fået et P for Perfekt! Tag den på, Percy, kom nu.” (“The mentor got a P for Perfect! Put it on, Percy, come on.”)

Maori—whose translator, Leon Blake, used every tool in his box—also preserved the “P.” But he replaced “prefect” with another word for leader (poutoko) that begins with “P.” “He P mō te poutoko! Kuhuna, Pēhi, kia tere…”

Malay also keeps the P by using the word pengawas (supervisor) for prefect: “P untuk pengawas! Pakailah, Percy.”

Foreign scripts: Hebrew, Uyghur, Japanese, and Hindi

Of course, the issue gets more complicated if your alphabet doesn’t even have “P.”

Gili Bar Hilel’s Hebrew translation offers a very clever solution:

“P for Percy — instead of M for Mentor!” (Mentor, or Madrich, is an equivalent position to Prefect in some Israeli schools.)Alimjan Azat’s Uyghur translation uses the Latin letter “P” in combination with a footnote: “The letter ‘P’ stands for class president (bashliqi degăn).” The accompanying footnote clarifies that that English word for bashliqi (president) and Percy both begin with that Latin letter “P.”

The Japanese translation (Yuko Matsuoka) and the Hindi translation (Sudhir Dixit) likewise embrace the British context of the situation. Japanese, like Uyghur, uses the Latin letter “P”: 監督生のP, kantokusei no P. Kantokusei clearly does not begin with P, but the Latin letter P tips off the average Japanese reader that the English word does.

Hindi—whose readers are very typically educated in British-style schools that use English as the language of instruction—preserves the familiar word prefect. But instead of using the Latin letter “P,” it spells out the letter as pī (पी): “Pī for Prefect!”

Evaluation

Each approach has its advantages. Molly, ever supportive, would certainly show her pride in Percy by stitching the letter of his prefecture into his sweater. And this strategy has literary merit in that it doubles down on the image of Percy as both a goodie-two-shoes and a momma’s boy.

Gili Bar-Hillel comes up with a smart solution for Hebrew, preserving the P for Percy while also tying the tease to the Madrich position so well known to Israeli schoolchildren. On the other hand, it’s not clear in this case why Percy would be ashamed of a sweater that has P for Percy. Perhaps being Prefect makes him too good to wear his mother’s handknit sweater.

But my favorite approach is that of Hannah Lützen. With the P for Perfekt, she successfully connects the first letter in Percy’s name with the twins’ recurring mockery of him as prefect, using a phrase (vejleder) for prefect that translates naturally into Danish language and life.

Explore this in your translations at home! Check out the Catalan, Ancient Greek, and Chinese translations, for instance, which each take their own interesting approaches. Let us know what you discover in the comments!

-

Harry Potter in the Classics: How Latin and Ancient Greek Captured a 20th Century Setting

Today’s post will offer a brief sampling of Harry Potter in the classical languages of Latin and Ancient Greek. I’ll say a few words about the translations and then follow them up with examples of how the two languages deal with modern technology, the magical world of Harry Potter, and modern cultural phenomena like Christmas, birthdays, and even homework.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in Latin (Peter Needham) and Ancient Greek (Andrew Wilson). If you enjoy this article, leave us some feedback in the comments about what you like or by contacting us to tell us what you’d like to see! You might also be interested in many of our other articles on topics like Harry Potter in Hebrew, Dumbledore’s favorite sweets, Harry Potter in a made-up language, and HP Japanese book art. Potter of Babble is also looking for contributions from readers like you, so please let us know if you have something you’d like to Babble about!

Introduction: Translating Children’s Books into Latin and Ancient Greek

Even though I studied Wheelock’s Latin as a kid and first engaged with anything Ancient Greek only as a young adult, I’m more familiar with Ancient Greek texts than Latin ones. And I can say the Ancient Greek translation is a true delight. It reads exactly like an Ancient Greek treatise, from the styling of the chapter titles (“On the Boy Who Lived“) right down to the sentence structure.

You do have to keep in mind that these books are meant to be approachable and fun for casual learners of these classical languages. I remember one friend taking a negative view of the Ancient Greek translation because it had some modernisms here or there. Both Ancient Greek and Latin make use of modern punctuation, for example. But, quite frankly, what does it matter if the publishers decided to use commas and em-dashes to aid the novice learner? Isn’t it more important that they create an enjoyable experience? (But to be fair, the translator does make some odd judgments, such as deriving Quirrell’s name [Κίουρος] from squirrel [σκίουρος].)

The Latin translation was born out of a broader phenomenon of translating children’s books into Latin. There’s Winnie Ille Pu (Winnie the Pooh), Cattus Petasatus (Cat in the Hat), and, as of 2015, Ubi Fera Sunt (Where the Wild Things Are). As far as I’m aware, Harrius Potter et Philosophi Lapis broke the mold for being the first full-length novel to be translated into Latin (along with its sequel Harrius Potter et Camera Secretorum. The translations were done by Peter Needham, a retired classics instructor at Eton College.

The Ancient Greek translation was inspired by the Latin translation, and is one of the only children’s books translated into Attic Greek. (Peter Rabbit and Max and Moritz have been translated into Koine Greek, which is much later and easier than Attic Greek.) One of the really neat things about the Ancient Greek translation is that the translator, Andrew Wilson, has a website that explains some of his translation choices in the first 5 chapters. As he mentions, his translation is entrenched in Ancient Greek literature, from Aristophanes to Hippocrates to Lucian.

How do Ancient Greek and Latin deal with modern technologies?

Modern tech is the first and possibly the most evident place in which the translation approaches of Needham and Wilson differed.

Needham relied on existing terms that are already used by the Roman Catholic Church, which continues to keep Latin alive into the present as a lingua franca. The words below can all be found in the Lexicon recentis latinatis, the dictionary of the Roman Curia. By using these established terms, Needham clearly intended for his translation to be read by modern students of Latin to practice their Latin. He didn’t create a text that exemplified the Latin of a Roman, but rather a text that would reflect the practical use of Latin as it’s used today.

A flying ship etched by Bartolomeu de Gusmão (1685–1724). Wilson, on the other hand, did seek to recreate an ancient text in all its conventional forms. Instead of relying on modern Greek for modern technologies and objects, he coined new terms that he intended to be comprehensible to someone from ancient Greece with a time machine. His typical strategy was to translate terms descriptively—someone from ancient Greece should be able to read a phrase like “tele-operated air-ship” and imagine something similar to a “remote-control airplane” (albeit they’d probably imagine something with sails and oars). A modern speaker of Greek, however, would be confused by the use of aeroskafos (“air-ship”) in place of the word aeroplano (“airplane”).

Latin Latin translation Ancient Greek Ancient Greek transliteration Ancient Greek translation video camera cinematographicam machinulam film machine τέχνημα κινηματογραφικόν technema kinematografikon film device remote-control airplane aeroplanum ex longinquo directum airplane controlled from a distance ἀερόσκαφος τηλεχειριστέον aeroskafos telecheiristeon tele-operated air-ship video games ludos computatorios computer game παίγνια ἠλεκτρονικά paignia elektronika electronic games VCR televisificum exceptaculum tele-vision receptacle μηχάνημα τηλεοπτικογραφικὸν mechanema teleoptikografikon tele-vision machine (flying) motorcycle birotula automataria automatic bicycle δικύκλου αὐτοκινήτου (πέρι αἰωρουμένου) dikyklou autokinetou (peri aioroumenou) (hovering) auto-kinetic bicycle Modern technologies in the Latin and Ancient Greek translations of Harry Potter. But even though the Latin and Ancient Greek translations use different strategies for their translations—Needham using established terms and Wilson creating new ones—we see definite similarities. The terms used in the two translations for “video camera,” “VCR,” and “motorcycle” are actually pretty close in meaning to each other. “Motorcycle,” for instance, is “automatic bicycle” in Latin and “auto-kinetic bicycle” in Wilson’s Ancient Greek. So the difference in strategy actually lies not in the words that the translators chose, but in Needham using conventional Latin terms while Wilson diverged from conventional Greek terms.

How do Latin and Ancient Greek deal with magic?

Magic was translated in either language using a variety of strategies depending on the word.

Latin Latin translation Ancient Greek Ancient Greek transliteration Ancient Greek translation wand baculum staff ράβδος ravdos rod vampires sanguisugi bloodsucker Λαμίας Lamias Quidditch Ludus Quidditch Quidditch the Sport Ἰκαροσφαιρική Ikarosfairike Icarusball poltergeist idolon clamosum clamorous spook δαιμόνιον daimonion demon Remembrall Omnimemor Remember-all παντομνημονευτικος pantomnemoneutikos Remember-all knuts Knuces κονιδας konidas Hufflepuff Hufflepuff Ὑφέλπυφος Yfelpyfos The magical wizarding world words used in the Latin and Ancient Greek translations of Harry Potter. Many magical objects, like “wand” and “Remembrall,” were translated pretty literally in both languages. Proper nouns invented by Rowling, like Quidditch and Hufflepuff, remained as such in Latin. Some culture-specific words, like “vampires” and “poltergeist,” were treated descriptively in Latin as “bloodsucker” and “clamorous spook.”

Wilson’s Ancient Greek translation, on the other hand, tried to incorporate Greek mythology where it could. Quirrell encountered lamias, rather than vampires, in the forest. It’s a reference to Lamia, a female nightcrawler known for seducing young men in order to feed upon them. Peeves is called a demon rather than a poltergeist. Although “demon” came to denote an evil spirit in Greek Christianity, a demon earlier referred to any supernatural being with disruptive behavior. Some demons might rain on your parade, but others could actually brighten up your rainy day.

The Greek word for “Quidditch,” ikarosfairike, is a combination of “Icarus” and “ball.” Icarus is a figure of Greek mythology well-known for flying high to reach a certain golden ball—the Sun. It’s only fitting that ancient Greek wizards would relate the Icarus story to a game whose goal is to catch the elusive Golden Snitch on a flying broom!

How do Latin and Ancient Greek deal with other cultural phenomena?

Modern cultural phenomena in Harry Potter presented another challenge to the translators of these ancient languages. Things like Halloween and birthdays accompany important plot points and are not easily replaced. Let’s take a look at how they were dealt with:

Latin Latin translation Ancient Greek Ancient Greek transliteration Ancient Greek translation Halloween Vesper Sanctus Holy Night Νεκύσια Nekysia Nekysia Christmas festum nativitatis Christi Feast of Christ’s Nativity Χριστούγεννα Christmas “Happy Birthday” Felix Sis Die Natali May Your Birthday Be Happy Χρόνια πόλλα Many Years “They piled so much homework on them that the Easter holidays weren’t nearly as much fun as the Christmas ones” tot pensa domestica eis ingesserunt ut feriae paschales haudquaquam tam iucundae essent quam brumales So much homework was given to them that the Easter holidays weren’t at all as pleasant as the winter holidays περὶ τὰ κατ’ οἷκον μαθητέα προστιθέντες πλείω ἐπὶ πλείοσιν, ὥστε οὐκ ἦν τοσοῦτο ἐν τῃ πασχαλινῃ ἀναπαύλῃ εὐφραίνεσθαι ὅσον ἐπὶ τῶν Χριστουγέννων More and more was added to the homework, so that there wasn’t as much merriment during the Easter holidays as the Christmas holidays Words for holidays in the Latin and Ancient Greek translations of Harry Potter. The modern Christian holidays of Christmas and Easter are preserved in both languages. Halloween is translated simply “Vesper Sanctus,” or Holy Night, in Latin. It’s used to refer to a celebration on the night before any sacred festival. In this case, it’s Halloween (which, as “All Hallow’s Eve,” originated as the evening celebration before the very sacred day of All Saints in Catholicism).

In Wilson’s Ancient Greek, Halloween becomes Nekysia, an ancient Athenian festival for commemorating the dead. Like many of the All Saints’ Day (or Día de los Muertos) traditions of today, Nekysia was marked with an offering for the dead, a banquet, and even attempts to interact with the dead. It was very much Athens’ Halloween, in a way. The only problem is that the timing isn’t right for the timeline of Harry Potter: Nekysia took place in the springtime, not in the fall.

As a final note, I took a look at how Harry’s birthday is treated in these translations because, well, the tradition of celebrating birthdays is only a couple centuries old! In Latin, Hagrid simply wishes that Harry’s birthday be a happy one. In the Ancient Greek translation, Hagrid wishes him “Many years!”—the formal way in Ancient Greek to wish someone good health on any annual holiday.

-

Ready to be part of the Babble?

Potter of Babble is growing in reach! Both in content and in followers. We now have regular readers from the United States, Canada, Japan, the UK, Germany, and Australia, and search engines have brought in traffic from all over, including China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sweden, Singapore, and Ecuador! Recently Potter of Babble has even been picked up by Google, where it already appears in one of the FIRST slots for some search terms.

As we continue to grow, we hope to optimize user experience. But we need your help in building a bigger, better Babble community:

Have something exciting to share about your favorite edition of Harry Potter?

Consider writing for us! We’re more than happy to feature content written by our readers and are searching for regular contributors who can write for us every 1–2 months. Get in touch here or on Instagram.

Have ideas on how we can improve?

Your feedback is INCREDIBLY valuable. Without it, we cannot tailor either content or design to fit your wants and needs. Like our posts, leave comments, and send us suggestions!

Sign up to help refine the Spellman Spectrum!

The Spellman Spectrum, which rates Harry Potter translations is still being tried and tested. We need people fluent in reading various languages to help with testing and feedback and are currently working on ways to get your involvement. If you’re interested in helping out, let us know.

Like us and stay connected!

Potter of Babble offers opportunities to connect with the broader collecting community, through our Google Group, our Instagram, Twitter, and more. It’s a great way to find good deals on rare books, too! Interacting with Potter of Babble helps expand our reach and grow our community: so like our posts, comment on them, and tell your friends.

Lastly, we just want to say thank you to all of you for your readership and your support. We would have not made it this far without you!

-

Japanese book art in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Let’s have a look at some of the book art from the Japanese edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone ハリー・ポッターと賢者の石 (Harii Pottaa to Kenja no Ishi) by Dan Schlesinger.

A Harvard-educated New York lawyer, Schlesinger seems on the surface like an unlikely candidate for illustrating a Japanese edition. But as he discusses in the Ted Talk below, the connection actually isn’t tenuous at all. He learned Japanese as a young adult and learned traditional Japanese woodblock printing while practicing law in Japan. It was during that time that he was approached by a largely unknown publishing house looking for new titles to publish, and Schlesinger recommended a still little-known book his 9-year-old son happened to be reading: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The publisher then commissioned him, Schlesinger, to illustrate the book.

Now, let’s take a look at those first illustrations that started off his fulfilling career as an artist:

ㅤ

It was on the corner of the street that he noticed the first sign of something peculiar — a cat reading a map. For a second, Mr. Dursley didn’t realize what he had seen — then he jerked his head around to look again.

There was a tabby cat standing on the corner of Privet Drive, but there wasn’t a map insight.

What he could have been thinking of? It must have been a trick of the light.ㅤ

ㅤ

Dudley paraded around the living room for the family in his brand-new uniform. Smeltings’ boys wore maroon tailcoats, orange knickerbockers, and flat straw hats called boaters. They also carried knobbly sticks, used for hitting each other while the teachers weren’t looking. This was supposed to be good training for later life. Harry didn’t trust himself to speak. He thought two of his ribs might already have cracked from trying not to laugh.

ㅤ

ㅤ

The giant sat back down on the sofa, which sagged under his weight, and began taking all sorts of things out of the pockets of his coat:

a copper kettle,

a squashy package of sausages,

a poker,

a teapot,

several chipped mugs,

and a bottle of some amber liquid that he took a swig from before starting to make tea.ㅤ

ㅤ

HOGWARTS SCHOOL OF WITCHCRAFT AND WIZARDRY

Dear Mr. Potter,

We are pleased to inform you that you have been accepted at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Please find enclosed a list of all necessary books and equipment.Yours sincerely,

Minerva McGonagallㅤ

ㅤ

And the fleet of little boats moved off all at once,

gliding across the lake, which was as smooth as glass.

Everyone was silent, staring up at the great castle overhead.

It towered over them as they sailed nearer and nearer to the cliff on which it stood.ㅤ

ㅤ

A bundle of walking sticks was floating in midair ahead of them,

and as Percy took a step toward them they started throwing themselves at him.

There was a pop, and a little man with wicked, dark eyes and a wide mouth appeared,

floating cross-legged in the air, clutching the walking sticks.

At the very end of the corridor hung a portrait of a very fat woman in a pink silk dress.

“Password?” she said.

“Caput Draconis.”ㅤ

ㅤ

Snape swept around in his long black cloak, watching them weigh dried nettles and crush snake fangs, criticizing almost everyone except Malfoy. This was so unfair that Harry opened his mouth to argue, but Ron kicked him behind their cauldron. “Don’t push it,” he muttered, “I’ve heard Snape can turn very nasty.”

ㅤ

ㅤ

He’d done it, he’d shown Snape. . . And speaking of Snape. . . A hooded figure came swiftly down the front steps of the castle. Clearly not wanting to be seen, it walked as fast as possible toward the forbidden forest. Harry’s victory faded from his mind as he watched. He recognized the figure’s prowling walk. What was going on? In a shadowy clearing stood Snape, but he wasn’t alone. Quirrell was there, too.

ㅤ

ㅤ

Petrified, he watched as Quirrell reached up and began to unwrap his turban. What was going on? The turban fell away. Quirrell’s head looked strangely small without it. Then he turned slowly on the spot. At once, a needle-sharp pain seared across Harry’s scar; his head felt as though it was about to split in two.