Home

-

Harry Potter in Asturian (and how Hagrid is unique in a language of 250,000 speakers)

This article has a companion article that provides additional context: Asturian Language: The Story of Bable and Its Features.

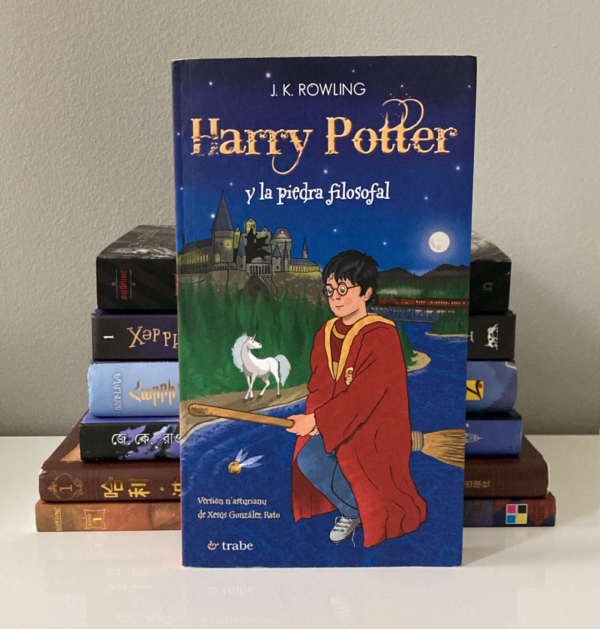

One of the most difficult translations of Harry Potter to access is the Asturian Harry Potter y la piedra filosofal (ISBN 84-8053-549-0 / 978-84-8053-549-6), whose name is identical to the Spanish title. With its unique font and cover art (by Samuel Castro González), the number of people seeking a copy may even exceed the 700 (!) copies ever printed. So we thought we’d offer readers a little taste of what’s inside the book.

Illustration

The cover art draws immediate attention to the fantastical magic within the book’s pages. In the foreground Harry rides prominently on a broom as a unicorn stares up at him from the edge of the Forbidden Forest. The full moon hanging in the background illuminates both the unicorn and the night sky around it. The cover’s hue darkens as your eyes venture upwards from the moon’s luminosity. At first glance, the pointy silhouette of Fluffy (or Peludín in Asturian) in the castle (enlarged ominously on the back cover) resembles three witches’ hats that echo our trio of Harry, Ron, and Hermione.

Set against the dark blue backdrop of a starry night sky, it’s the only Harry Potter cover that captures the first visual impression of Hogwarts that we get from the novel itself: “Perched atop a high mountain on the other side, its windows sparkling in the starry sky, was a vast castle with many turrets and towers.” (See below for the translation in both Asturian and Spanish.)

Asturian: Mangáu no cimero un monte altu nel otru llau, coles ventanes relluciendo en cielu estrelláu, había un castiellu escomanáu con abondes torres y torretes.

Spanish: En la punta de una alta montaña, al otro lado, con sus ventanas brillando bajo el cielo estrellado, había un impresionante castillo con muchas torres y torrecillas.Although it was published in 2009—eight years after the Warner Bros. film premiered in cinemas—it bucks the iconic Scholastic font in favor of something more plain yet marvelous and fleeting like a shooting star. The binding of the book, meanwhile, stands in a stark red contrast to the blue front and back.

Language, translation, and content

The translation into Asturian was done by Xesús González Rato, a medic by profession but a seasoned translator on the side. He’s brought at least a dozen foreign language works into Asturian, at very little pay. For his translation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days, he received some 1,800 euros.

TV advertisement for the Asturian translation. The title was almost translated as Harry Potter y el piedru filosofal to distinguish it from the Spanish title. (Those of us who have tried to track down copies of this book would have been very grateful for that title.) The word piedru is found in Asturian dictionaries as a synonym for piedra. But it’s not a well-known variant by Asturian speakers, so that title was nixed. An alternative title was floated (Harry Potter y l’elixir de la vida, “Harry Potter and the Elixir of Life”) but the idea to stray from the English title ultimately didn’t sit well.

So how does the story read in Asturian? As we love to do at Potter of Babble (or, in this post, Potter of Bable), let’s start with the very beginning and compare it with the Spanish translation:

English: Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much. They were the last people you’d expect to be involved in anything strange or mysterious, because they just didn’t hold with such nonsense.

Asturian: El señor y la señora Dursley, del númberu cuatro del Camín de los Sanxuaninos, taben arguyosos de dicir que yeren dafechamente normales, gracies al cielu. Yeren les postreres persones qu’ún esperaría ver envueltes en coses rares o misterioses, porque nun podíen ver babayaes asemeyaes.

Spanish: El señor y la señora Dursley, que vivían en el número 4 de Privet Drive, estaban orgullosos de decir que eran muy normales, afortunadamente. Eran las últimas personas que se esperaría encontrar relacionadas con algo extraño o misterioso, porque no estaban para tales tonterías.You can listen to this paragraph read aloud over at Carly and Harrison’s The Book That Lives project.

Already we can say a few things about the Asturian translation in comparison with the better known Spanish translation. We immediately notice linguistic differences, like the feminine plural -es (gracies, coses rares o misterioses, babayaes) and the masculine -u (númberu, cielu) and the neuter -o (cuatro), which are distinctive features mentioned in our earlier post about the Asturian language.

Another observation is in the difference (and similarity) in translation strategy. On the one hand, they take very different approaches to translating the phrase “thank you very much.” The Asturian text translates the phrase as gracies al cielu (“thank heavens”), an expression of relief that the Dursleys are normal people. (This is the same approach taken by the translators of the Catalan, Portuguese, and Occitan editions.) The Spanish text, by contrast, translates it as afortunadamente (“fortunately”), an expression that emphasizes how proud the Dursleys are to be normal.

The translation of “they just didn’t hold with such nonsense” is similar in both languages. The Asturian translation is porque nun podíen ver babayaes asemeyaes (“because they couldn’t come off as blabbermouths”), while the Spanish has porque no estaban para tales tonterías (“because they weren’t for such nonsense”). The Spanish translation conveys the original English phrase more literally, however, while the Asturian provides a little more colloquial pizzazz with its use of the slang word babayaes.

Overall, this seems to illustrate the approach that the Asturian translation takes. Like Spanish, it’s relatively faithful to the English original. But it’s much more colloquial than the Spanish, presumably to ensure the translation has a sufficient Asturian flavor.

Notably, the translation nativizes a surprising amount of the proper nouns in the novel for such a late translation. After the Harry Potter films made their mark in franchising, this became an uncommon feature in new translations. Here are a few select examples in the table below:

English Asturian Derivation and meaning knuts kuenxus From cuenxu (nut) sickles focetus From focetu (sickle) galleons galeonis From galeón (galleon) golden snitch raitana dorada From raitana (robin) and dorada (golden) bludger porriador From porriador (pounder) quaffle cuatriada Name of the ball used in Asturian bowling (called bolos); so named because the ball is used to knock down pins in a square (cuadru). Cleansweep Seven (the broomstick) Espolvadora Siete From espolvar (dust off) Oliver Wood Oliver Maderu From maderu (log) Fang Canil From canil (fang) Fluffy Peludín From peludín (fluffy) goblin duende From duende, a category of small humanoid creatures that often live one’s house and cause mischief (similar to the puck) chocolate frogs xaronques de chicolate From xaronca (frog) and chicolate (chocolate) Bertie Botts Every Flavor Beans gominoles Bertie Bott de tolos tastos From gominola (gummy), tol (all), and tastu (flavor) You-Know-Who El-Qu’Usté-Sabe / El-Que-Tu-Sabes Literally, He-Whom-You-Know-Of. Usté is used when talking to a stranger or a superior. Tu is used with peers. Bathilda Bagshot Balbina Sacurrotu From sacu (bag) and rotu (broken) Emeric Switch Eméritu Tornadures From tornador (switch) Newt Scamander Lleontín Scavera From sacavera (salamander); the word for newt is guardafoentes (literally, fountain guardian) and not a good personal name. The Asturian personal name Lleontín means “little lion.” Leaky Cauldron El Calderu Afuracáu From calderu (cauldron) and afuracáu (holey; used to describe someone who spends carelessly, such as someone who runs a large tab) Ollivander Olivarines May be invoking olivar, meaning “to pine for” something, perhaps a reference to the role of one’s personality in the type of wood used for your wand. Quidditch through the Ages Quidditch al traviés de los tiempos From al traviés (across) and tiempos (time) Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Animales fantásticos y ú los atopar From ú (where) and atopar (find) The most iconic proper nouns, of course, have remained the same: Gryffindor is still Gryffindor, Albus Dumbledore is still Albus Dumbledore, and Hogwarts is still Hogwarts.

According to González Rato, Philosopher’s Stone in Asturian was considered a success. He completed a translation for the second book, which was scheduled for publication in December 2013. It never was published, though, and no reason has been given, but the fact that it took two years to get the permissions to publish the first novel might lend a hint.

Hagrid in Asturian

So how do you represent a character like Hagrid in a language that’s small both geographically and in number of speakers? Luckily, Asturian has no shortage of dialectal variation! Hagrid is reimagined as a native of Ciañu, a small mining town along the Nalón river to the southeast of Asturia’s capital of Ovieda.

The accent in Ciañu is characterized especially by certain changes to the vowels, like the raising of “o” and “e” to “u” and “i” in certain instances. Take, for instance, how Hagrid says cuántos díes (“how many days”) and vos (“you guys”) in the following:

— ¿Cuántus díis vus quedin pa lis vacacionis? — entrugó Hagrid.

“How many days you got left until yer holidays?” Hagrid asked.See also the following (and compare how he says moto, bones nueches, and señor):

— Voi devolve-y a Sirius la motu. Bonis nuechis, profesora McGonagall, profesor Dumbledore, siñor.

“I’ll be takin’ Sirius his bike back. G’night, Professor McGonagall — Professor Dumbledore, sir.”Not only does Hagrid speak a real, non-standard Asturian accent, but the accent chosen by the translator is as clearly provincial to the Asturian reader as his accent is in English.

A Taste of Harry Potter in Asturian

Now let’s take a look at a specific scene in the novel, featuring some iconic moments and characters, and compare the translation in Asturian and Spanish:

English (J.K. Rowling) Asturian (González Rato) Spanish (Rawson) Notes The egg was lying on the table. There were deep cracks in it. Something was moving inside; a funny clicking noise was coming from it. El güevu taba na mesa. Tenía delles regalles. Dientro movíase daqué y facía unos chasquíos estraños. El huevo estaba sobre la mesa. Tenía grietas en las cáscara. Algo se movía en el interior y un curioso ruido salía de allí. Compare Asturian güevu vs. Spanish huevo (egg), an iconic difference between the two languages. They all drew their chairs up to the table and watched with bated breath. Toos averaron les sielles a la mesa y aguardaron ensin respirar. Todos acercaron las sillas a la mesa y esperaron, respirando con agitación. All at once there was a scraping noise and the egg split open. The baby dragon flopped onto the table. It wasn’t exactly pretty; Harry thought it looked like a crumpled, black umbrella. Its spiny wings were huge compare to its skinny jet body, it had a long snout with wide nostrils, the stubs of horns and bulging, orange eyes. Hebo un ruíu y el güevu abrió. La cría de dragón dexóse cayer na mesa. Nuna yera precisamente guapu; Harry pensó qu’asemeyaba un paragües prietu arrugáu. Les sos ales espinoses yeren escomanaes comparaes col so esmirriáu cuerpu prietu, tenía un focicu llargu coles narines anches, esbozos de cuernos y güeyos saltones color naranxa. De pronto se oyó un ruido y el huevo se abrió. La cría de dragón aleteó en la mesa. No era exactamente bonito. Harry pensó que parecía un paraguas negro arrugado. Sus alas puntiagudas eran enormes, comparadas con su cuerpo flacucho. Tenía un hocico largo con anchas fosas nasales, las puntas del os cuernos ya le salían y tenía los ojos anaranjados y saltones. Two other iconic differences appear here: Asturian focicu vs. Spanish hocico (snout) and Asturian güeyos vs. Spanish ojos (eyes). It sneezed. A couple of sparks flew out of its snout. Espirrió. Saliéron-y delles chispes del focicu. Estornudó. Volaron unas chispas. Notice the Asturian text more accurately follows the English text, here and elsewhere in this scene. “Isn’t he beautiful?” Hagrid murmured. He reached out a hand to stroke the dragon’s head. It snapped at his fingers, showing pointed fangs. —¿Nun ye preciosu, ho? –marmulló Hagrid. Allargó una mano pa cariciar la cabeza del dragón. Esti taragañó-y los deos, amosando unos caniles puntiaos. —¿No es precioso? —murmuró Hagrid. Alargó una mano para acariciar la cabeza del dragón. Este le dio un mordisco en los dedos, enseñando unos comillos puntiagudos. The Asturian text adds “ho” to Hagrid’s comment for greater, colloquial effect. “Bless him, look, he knows his mommy!” said Hagrid. »¡Benditu sía, mirái, conoz a so ma! –dixo Hagrid. —¡Bendito sea! Mirad, conoce a su mamá —dijo Hagrid. “Hagrid,” said Hermione, “how fast do Norwegian Ridgebacks grow exactly?” —Hagrid –dixo Hermione–, ¿cómo medren de rápido los llombucrestaos noruegos, exautamente? —Hagrid —dijo Hermione—. ¿Cuánto tardan en crecer los ridgebacks noruegos? Asturian translates Ridgebacks as llombucrestaos while Spanish retains ridgebacks. Hagrid was about to answer when the color suddenly drained from his face — he leapt to his feet and ran to the window. Hagrid diba retrucar cuando de sópitu marchó-y tola color de la cara… Llevantó d’un saltu y corrió pa la ventana. Hagrid iba a contestarle, cuando de golpe su rostro palideció. Se puso de pie de un salto y corrió hacia la ventana. “What’s the matter?” —¿Qué pasa? —¿Qué sucede? “Someone was lookin’ through the gap in the curtains — it’s a kid — he’s running back up ter the school.” —Había daquién mirando pela regalla lis cortinis… Ye un rapaz… Vuelve corriendo pal colexu. —Alguien estaba mirando por una rendija de la cortina… Era un chico… Va corriendo hacia el colegio. Pronouns are one of the major differences between the languages. Here we see Asturian daquién vs. Spanish alguien (somebody). Harry bolted to the door and looked out. Even at a distance there was no mistaking him. Harry echó a correr pa la puerta y miró afuera. Inda a aquella distancia nun había dubia. Harry fue hasta la puerta y miró. Incluso a distancia, era inconfundible: Malfoy had seen the dragon. Malfoy viera’l dragón. Malfoy había visto el dragón. If you enjoyed this article, check out its companion on the Asturian language to learn more and to find out what resources you can use to help you read your copy of Harry Potter in Asturian!

As always, happy exploring!

-

Asturian Language: The Story of Bable and Its Features

Asturian is a language you’ve probably never heard of. Unless you’re a history buff, a Spain aficionado, or, well, a Harry Potter collector. The Romance language, spoken in the northwestern autonomous region of Spain called Asturias, has only 250,000 speakers, of whom less than half likely have native proficiency. But it has an absolutely fascinating history!

There aren’t many brief introductions to Asturian online, so I thought I’d offer a little tour de la langue here at Potter of Babble. I’ll start below by outlining a few of the similarities with Spanish, followed by some of the differences. Then I’ll continue with a brief history of the Asturias region and its language, interweaving its history with that of Spanish. Then I’ll end the post with some frequently asked questions and a brief list of resources for learning more.

ㅤ

Features that Distinguish Asturian: Selected Examples

Map showing distribution of Asturian speakers in northern Spain. [Source: Denis Soria. CC BY-SA 3.0.] ㅤ

Central Asturian, the standard variety, shares some glaring features with Spanish that are usually considered distinctive:

- “Breaking” of short e and o: piedra and puerta (compare pedra and porta in Portuguese)

- Forms of the definite article “the”: el, la, and lo (although lo is used differently in Spanish)

- Changes to words like Latin clamare (‘call’), clavem (‘key’), and pluviam (‘rain’): llamar and llave and lluvia (vs. chamar and chave and chuvia in Portuguese)

But Central Asturian is also distinguished by a number of differences. Some of those differences reveal features inherited from Latin but were lost in Spanish:

- Masculine nouns end in -u in the singular: cuerpu (compare Spanish cuerpo; a conservative retention from Latin’s masculine accusative case, –um.)

- Feminine nouns end in –es in the plural: vaques (compare Spanish vacas; possibly a retention of Latin –es in the 5th Declension?)

- Neuter nouns (neutru de materia) end in –o. (A retention of the Latin ablative case.)

- These mark collective or generic nouns and cannot take a plural form. Compare el pelu roxu (‘the strand of red hair’) versus lo pelo roxo (generic ‘red hair’).

- Retention of f at the beginning of a word: facer (compare Spanish hacer)

Others differences were once shared with Spanish, but have since been lost in Spanish:

- Retention of x pronounced as ‘sh’ (in Spanish merged with j to become ‘h’ in the 15th century): dixo (compare Spanish dijo)

- Retention of pronominal objects at the end of conjugated verbs: tráxome la comida (compare Spanish me trajo la comida)

Asturian has also had some innovations of its own:

- More widespread breaking of e and o than in Spanish:

- Before ‘y’: güei (compare Spanish hoy)

- In the verb ser: ye (compare Spanish es)

- Change of ‘h’ to ‘g’ before ‘ue’: güevu (compare Spanish huevo)

ㅤ

The Story of Asturian, and How Spanish Took over Spain and the New World

The historical claim to fame of the Asturias region is as the birthplace of the Reconquista. Histories of Asturias typically begin with the 8th century, when the Arab-Berber conquests of the Iberian peninsula caused the collapse of a decaying Visigothic kingdom. The power vacuum allowed the peninsula to be taken over in a rapid sweep. Under the leadership of a warrior called Pelayo (Pelagius), the region of Asturias successfully resisted the invasion, aided by the natural barrier of the Cantabrian Mountains and becoming one of the only corners of Iberia where Islamic rule would never take hold.

ㅤ

Painting of Pelayo by Luiz de Madrazo y Kuntz, 1853–56. ㅤ

The Iberian peninsula in the mid-8th century, with the Kingdom of Asturias in the north. [Source: Amitchell125. CC BY-SA 4.0.] ㅤ

The forces of Asturias established a garrison in Oviedo, atop a hill surrounded by mountains, and consolidated the region into the peninsula’s first Latinate kingdom since the fall of the Roman Empire. The Asturians had kept many of the customs of the Romans, produced literature in Latin, and likely spoke a primordial form of Romance. Spanish historiography has long held a dynastic continuity from the Visigoths to Pelayo and his successors, but that claim is highly suspicious. In all likelihood, the new kingdom of Asturias was no more Visigothic than the Arab-Berber caliphate in Córdoba was.¹ Still, there is no doubt that Asturias became the formative cultural and linguistic link between modern Spain and the late Roman era.

Asturias reached its zenith with Alfonso III, who is remembered in Spanish history as “Alfonso the Great.” The Catholic king had launched a successful assault against the Muslim invaders, pushed them out of their northernmost territories, and sent Christians from Asturias to “repopulate” the captured lands (which, it should be noted, had been predominantly populated by Christians anyway). The expansion was well-regarded back home, not least because the capture of resourceful land brought wealth and prosperity to Oviedo’s rugged terrain. Alfonso III thus set the stage for the Reconquista and, many centuries later, the dominance of the Romance languages over the whole of the peninsula. The expansion had at last made Asturias prosperous, and securing the city of León was its greatest prize. After some wrangling among Alfonso’s sons, the kingdom’s capital shifted to León.

Securing the city of León was the greatest prize of Alfonso’s expansion and, after some wrangling among his sons, the kingdom’s capital shifted south to that city. It was during this period that the earliest documents written in Iberian Romance begin to appear. A 10th-century list of cheese and the 12th-century Fuero d’Avilés are among them, and many have reasonably argued that they more closely reflect the language of Asturias than the language of Spanish.²

Omne poblador de Abiliés quanta heredat poder comparar de fora, de terras de villas, seía franca de levar on quesir, é de vender, é de dar, et de fazer de ela zo qu’il plazer; et non faza per ela neguno servitio.

Excerpt from the Fuero d’Avilés

A man living in Avilés, as much property as can be bought from outside the towns’ lands, will be free to take wherever they want, to sell, to give, and to do with it as he pleases; and without doing any service for it.

Fragment of the Fuero d’Avilés, which some linguists consider to be one of the earliest documentations of Old Asturian. ㅤ

With the epicentre of the kingdom shifted south of the Cantabrian range and more exposed to the Arab-Berber forces, the kingdom’s eastern frontier grew in importance as a buffer zone. Sparsely populated in the 10th century, that eastern region known as Castile was heavily fortified (hence its name from Latin castella, “castle”). Concentrating the kingdom’s military might far from the kings’ oversight proved destabilizing, though. By the end of the century, Castile was autonomous. And in the 11th century, Castile began to dominate. In the 13th century, the dynastic lines of León and Castile merged through Ferdinand III, the first-born son of the king of León and the infanta of Castile.

ㅤ

Iberian peninsula, c. 900, after the expansion of Asturias (in blue and yellow) and the establishment of Castile (yellow) as an autonomous county. [Source: Elryck. CC BY-SA 4.0.] ㅤ

Iberian peninsula, c. 1065, as Castile (yellow) begins to dominate the greater Asturian region. [Source: Elryck. CC BY-SA 4.0.] ㅤ

As León’s king and court were incorporated into the court of Castile, the kingdom saw a shift from the Asturian language to the Castilian language as its predominant dialect of Romance. Documents ceased being written in Old Asturian soon after as business was increasingly conducted in Castile. It was the Castilian language (castellano), the dialect of Iberian Romance spoken by elites in Castile’s capital of Toledo, that later became the language of government and the lingua franca of the Spanish empire: Spanish. The Old Castilian dialect was very closely related to the Old Asturian dialect in León, and they were so mutually intelligible that they were not likely considered separate languages at the time. But Castilian had undergone some distinctive changes not seen in Asturian. Among them was the change of f– to h– in words like in forno (Castilian horno). Moreover, the cosmopolitan dialect of Toledo, which had been under Arab rule for centuries, had imported a significant amount of Arabic expressions.³

Amid its ascent, Castilian eclipsed Asturian in literary output. Efforts in Toledo to standardize the language of government, especially from the reign of Alfonso el Sabio (Alfonso the Wise) on, formally stamped out Asturian as a written language. As far as we know, nothing was written in Asturian in the 14th and 15th centuries. Meanwhile, the Castilian epic El Cantar de mio Cid, an older composition in pre-Castilian Romance that nonetheless reflected the ethos of the Castilian dynasty, was coming into its final written form.

ㅤ

Expansion of Castilian Spanish from 1000 CE to 2000 CE. The name “Leonese” (green) is used in this map to represent Asturian. [Source: Alexandre Vigo. CC BY-SA 3.0.] ㅤ

In its expansionist phase, the kingdom of Castile carried out an aggressive form of cultural imperialism (at its peak, the Spanish Inquisition), making it necessary for anyone upwardly mobile to assimilate and embrace Castilian as their language. It did not, however, aim to stamp out other languages and dialects entirely, and several languages throughout Spain, like Asturian, survived as minority languages. As the dust settled on Castile’s domination of Spain, however, Asturians began writing in their local tongue again in the 16th century.

ㅤ

Antón de Marirreguera, fl. 17th century, one of the first people to write in modern Asturian. ㅤ

The oldest extant text in modern Asturian, Pleitu ente Uviéu y Mérida pola posesión de les cenices de Santa Olaya, was written in 1639 by Antón de Marirreguera. Why Asturian instead of Castilian? Well, as alluded in the title, the poem was entered into a contest of rhetoric to determine whether the relics of Saint Olaya (Eulalia), a regional patron, should be placed in Oviedo or Mérida. In the dialect of Oviedo, Antón wrote:

Si nos lleven esta Santa

No hay más d’arrimar la foz;

Dirán ellos: Morrió acá;

Diremos nos: Non morrió.

Q’está viva par’AsturiesIf they carry this Saint to us

There will be no need to go down into the gorge

They will say: She died there;

We will say: She hasn’t died.

For she is alive in Asturias.Excerpt from Pleitu ente Uviéu y Mérida (1639) by Antón de Marirreguera, the oldest extant work of modern Asturian literature. ㅤ

In these words we see a purposeful localism by Marirreguera. Not only did he make a powerful statement as to Saint Olaya’s importance to Oviedo over Mérida, but he drives it home by delivering it in Oviedo’s own form of expression.

Asturian expression began to flourish with the Spanish Enlightenment (of which the Asturian and statesman Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos was one of the most influential intellectuals). By the late 19th century we see clear signs of a linguistic awakening, with the publication of grammatical studies and compilation of dictionaries of the Asturian language.

Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (1744–1811), painting by Antonio Carnicero, c. 1797. ㅤ

At the same time, speakers of Asturian (frequently referring to their speech as Bable) became increasingly diglossic: using Asturian at home but Castilian Spanish in public. Industrialization and urbanization had brought many Asturians into cosmopolitan settings where Castilian Spanish was needed as the lingua franca. Not only did this diglossia relegate Asturian to the sidelines for many of its speakers, but many Asturians also began embracing the view that Bable was just a substandard form of Spanish.

In 1976, as Spain transitioned away from Francoism, the Conceyu Bable was born to advocate for the teaching of Asturian in schools. Four years later, it was replaced by the Academy of the Asturian Language. The Academy codified a standard set of spelling and grammatical rules for Asturian. With the support of the government, it helped cultivate a revival of the language, both literarily and educationally. In a positive turn for the language, a generation of Asturian youths gained a sense of pride and enthusiasm in using the language—a rarity among language revivalist efforts and a good sign for the language’s vitality. Asturian is now used in formal workplaces and classrooms, a stark reversal to its relegation to the mines and home. Because of its newfound support and prestige, the language is undergoing an age of renaissance, but with such a small community of speakers in such a big country, it remains to be seen how long that renaissance will last.

ㅤ

Frequently Asked Questions about Asturian and Spanish

What’s in a name? Bable and Castilian?

Asturian is often called “Bable,” a term of uncertain origin that may have once meant something along the lines of “everyday speech.” The term appears to be much older than “Asturian” and was the preferred term in the 1970s when the movement to revive Asturian first began. The term “Asturian,” which was first widely applied to the language in the 19th century, has grown in favor as the language has become increasingly associated with geographic location (i.e., spoken in Asturias) than with informal audience (i.e., friends and family instead of work and school). The term has been rejected by anti-leftists who assert that Spanish should be the sole language of Asturias; activists associated with El Club de los Viernes regionally and with Vox nationally tend to insist on the term Bable in effort to undermine Asturian’s legitimacy as a regional language.

Note that throughout the post I refer to Spanish as “Castilian” or “Castilian Spanish.” This reflects a distinction that’s actually made in Spanish literature itself: a distinction intended to highlight the fact that Spain is home to several closely related Romance languages, and the language known as “Spanish” has its origins in the Castile region.

Why isn’t Asturian considered Spanish?

Of all the Romance languages spoken in Spain and its environs, Asturian is the most like Castilian Spanish. Not only are they mutually intelligible, but Asturian shares a lot of phonological traits that are otherwise unique to Castilian Spanish. Vowel breaking of o → ue (puerta) and e → ie (piedra) is one example. Asturian has also borrowed a significant amount of vocabulary from Spanish. And to complicate things further, speakers of Asturian often engage in codeswitching between Asturian and Castilian Spanish. So it can be very easy for outsiders to mistake Asturian as just a substandard variant of Castilian Spanish.

But there are a number of reasons why it’s considered a separate language:

Asturian is “older” than Castilian. OK, this claim is misleading in a few different ways, but the exaggeration is meant to drive home a point. The first kingdom of Romance speakers in Spain was the Kingdom of Asturias, and it was out of Asturias that the first Romance texts came. The earliest preserved document said to have distinctive Asturian features, the Fueru d’Avilés (Act of Avilés; 1085 or 1155), was written in the 11th or 12th century. It was not until the late 12th century that documents portraying the vernacular of Toledo (i.e., Castilian) were written.

Modern Asturian retains old features that Castilian Spanish has lost. Or, for the more linguistically-oriented among you, Castilian Spanish has innovations not found in Asturian. The change of initial f– to h-, a distinctive feature of Castilian Spanish, never happened in standard Asturian.

Asturian may not be as closely related to Spanish as it appears. Some linguists, on neogrammarian assumptions, lump Asturian in a closer genetic relationship to Portuguese and Galician than to Castilian Spanish. But with the four West Iberian languages so close to each other, it’s difficult to say definitively whether this is true. Asturian may simply fall between Galician and Spanish in a dialect continuum.

Asturias is a distinct place with a distinct people. This reason may sound silly, but this is actually one of the most important factors in determining whether a language variety is a language or a variant/dialect: do the people who speak the language variety consider it a separate language? That’s usually enough to decide a variety is a separate language. If those people live within a distinct geopolitical boundary—such as the Principality of Asturias—that strengthens their ability to foster an independent literature, strengthening the claim that the language is separate.

ㅤ

Resources

Deprendi Asturianu – Lessons in Asturian Grammar (in Asturian, with references to Spanish)

Online Asturian-Spanish Dictionary – From the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana

Learn and connect – An old-school discussion forum of Asturian speakers. (As of the publication of this article in June 2023, the forum is active and the most recent post was in May 2023.)

A Linguistic History of Asturian – Not for the faint of heart. It’s a dissertation.

News in Asturian – The Asturies news site gives you new reading material on daily basis. Already know Spanish? Jump right in to these short articles and you’ll learn Asturian in no time!

Read the latest research on Asturian language and culture – Published by the Academia de la Llingua Asturiana

Buy books in Asturian – From publisher Ediciones Trabe

Varieties of Asturian – Introduction to the different dialects of Asturian (YouTube)

ㅤ

ㅤ

Footnotes

¹ It is often forgotten that the Arab-Berber invaders did not, for the most part, uproot the local populations—much of whom had collaborated with the invaders to overthrow Visigothic rule. The idea that the Asturian rulers continued the Visigothic line first appeared during the reign of Alfonso III “the Great,” as did the earliest surviving records of the Asturian dynasty.

Not coincidentally, Alfonso III engaged in a campaign to expand the borders of Asturias southward into Arab-Berber–ruled land. By claiming to represent the fallen Visigothic dynasty that the Arab-Berbers had toppled, he could justify his capture of territory as a Reconquista—reconquering land that the Asturians’ forebears, the Visigoths, had lost. (His Visigothic heritage was not all that he used to bolster support for his campaign, by the way: under his rule, Asturias became Roman Catholic Europe’s new Jerusalem after the bones of St. James had been allegedly found in Santiago de Compostela, more than 3000 miles from Jerusalem where he is said to have died.)

² The Royal Spanish Academy of Language includes these documents as the earliest examples of written Spanish. My expertise on this matter is limited. But since Asturian and Spanish continued to develop alongside each other as sisters during this period, it might be more accurate to say that these documents represent an ancestral form of both Asturian and Spanish. Indeed, the speakers of Old Asturian and Old Spanish probably considered themselves to be speaking the same language, which they interchangeably called by terms like romance, latín, fablar, and lengua. It is undeniable, however, that the center of culture at this time lay more in Asturias than in Castile, from whence Spanish was born.

³ Centuries later, most of those Arabic expressions were also brought into Asturian through Castilian. i’ve been careful to highlight the oft overlooked significance of Asturias and the Asturian language to the history of Spain and the Spanish language. But it must also be noted that Asturias and its language did not develop in a vacuum any more than Castile or its language. Although the Arabs minimally influenced the Asturian language before the 16th century, they did have a formative impact on Asturian identity and self-expression as early as the 8th century. Likewise, the Asturian language, which today looks nothing like the Latin that the Romans had brought to Spain, has been very visibly influenced by the Galicians to the west and the Basques to the east, and has introduced a number of innovations of its own. Thus there’s no veracity to the idea that Asturian represents a pure, unadulterated Romance—a view associated with the regionalist ideology known as Convadaguismo.

-

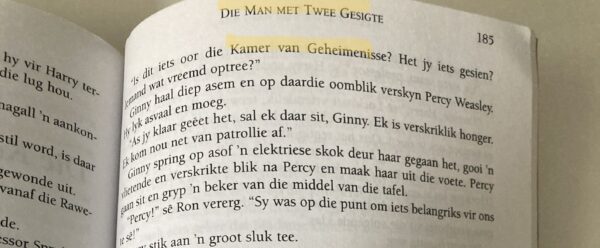

Printing error: Chamber of Secrets in Afrikaans

Today I was taking a look through Harry Potter en die Kamer van Geheimenisse (Afrikaans Chamber of Secrets, translated by Janie Oosthuysen). I happened across this printing error in Chapter 16. The page header says “Die Man met Twee Gesigte” (“The Man with Two Faces”) throughout the chapter.

I’ve highlighted it in the image below, which is taken from the third print in May 2000. The words Kamer van Geheimenisse (Chamber of Secrets) appear just below the header, making for a stark comparison between text from Philosopher’s Stone and text from Chamber of Secrets.

The title of Chapter 16 in fact? “Die Kamer van Geheimenisse” (“The Chamber of Secrets”).

-

87 Translations of Harry Potter. What Languages Could Be Next?

As of April 2023, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone has been formally* translated into 87 languages. Only a handful of books have been translated into more languages, and Philosopher’s Stone may be the only full-length novel** to be fully translated into so many languages. That’s a huge part of the reason enthusiasts of language, literature, and translation have taken to collecting translations of the book, although the type of writing, amazing cover art from around the world, and just plain old Harry Potter fandom are also big reasons.

With translations obscure as Asturian (Harry Potter y la piedra filosofal), Breton (Harry Potter ha Maen ar Furien), Greenlandic (Harry Potter ujarallu inuunartoq), and Māori (Hare Pota me te Whatu Manapou), collectors are always asking: what languages could be next?

Below we take a look at 5 of the most likely contenders for a Harry Potter translation and explain the reasons why they might be the next language to enjoy a translation (as well as some of the obstacles that may prevent those translations from coming about).

Amharic

Amharic boasts some 50 million speakers, primarily in Ethiopia where it serves as the primary language of instruction and, until 2020, it was the country’s sole official language. There are also high concentrations of Amharic speakers in Israel and in some parts of the United States. An Amharic translation, whose title might be ሃሪ ፖተር እና አስማተኛው ድንጋይ (Häri Potär əna äsmatäñaw dengay), would have to go up against at least one unauthorized translation already circulating in Ethiopia, though.

Kurdish

The number of Kurdish speakers is not known, but reasonable estimates place the number between 20 and 40 million. Kurdish speakers are highly literary, and it’s likely that a Kurdish translation of Harry Potter would be highly marketable in Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq where Kurdish is spoken. But it’s the location of Kurdish speakers that may actually be one of the biggest obstacles: the Kurdish market spans four countries, and awarding distribution rights would be difficult in any of those four countries, let alone all of them. The best bet for a Kurdish translation, for what it’s worth, would be in northern Iraq in the Sorani dialect. One possible title may be هاری پۆتەر وبەردی جادووگەرەکە (Harî Poter wiberdî jadûger eke). In Turkey, in the Kurmanji dialect, the title would be Harry Potter û Kevirê fîlozof and written in the Latin alphabet.

Swahili

Swahili is a favorite among collectors, in part because it’s the most widely spoken language that is native to Africa. Possible titles include Harry Potter na Jiwe la Mchawi or Harry Potter na Jiwe la Mwanafalsafa. But the countries where Swahili books are most often published, Kenya and Tanzania, share a problem with India, South Africa, Pakistan, and the Philippines—countries where translations of Harry Potter have been notoriously difficult for publishers to sell. A huge portion of the literate population in these countries can read English, and they would probably prefer to read Harry Potter in English.

Neo-Aramaic or Classical Syriac

Speakers of Neo-Aramaic are a small but strong community with a rich literary tradition that spans millennia. There are some 1–2 million speakers worldwide, who have largely been dispersed from Iraq in recent decades. But there’s been tremendous and decently funded effort to keep the language alive. There’s no doubt that a Harry Potter translation into Classical Syriac, the literary dialect, would sell tens of thousands of copies. The U.S.-based Gorgias Press would surely commission a great translation if the Blair Partnership offered it the rights. A possible title would be ܗܐܪܝ ܦܘܛܪ ܘܟܐܦܐ ܕܦܝܠܘܣܘܦܐ (Hāri Poṭer wə-kipā də-pilosofā).

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic made the list not because the language and market are strong—fewer than 100,000 people in Scotland can read Scottish Gaelic—but because there was actual effort in this direction at one point. According to Potterglot, Bloomsbury had plans to publish a Scottish Gaelic translation in 2006 and even registered an ISBN and a title: Harry Potter agus Clach an Fheallsanaich. It never came to fruition because the publisher couldn’t find a translator. But we know that if they ever do find one, a lot of people who don’t know Scottish Gaelic would definitely be buying copies!

Footnotes

* This number only includes translations that have been legally authorized. If we count unauthorized translations, the number of languages falls somewhere around 95. Why make the distinction? Because while unauthorized translations are often done well, some of them are so sloppy that they can’t really be called a translation. Authorized translations are typically higher in quality: they are usually translated by experienced professionals who are good writers and go through a formal editing process to ensure clarity and consistency.

** Much shorter novels like Adventures of Pinocchio, Alice in Wonderland, and Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet have been translated into more languages, but none of these exceed 30,000 words. (For comparison, Philosopher’s Stone is 77,000 words in length.) Portions of Don Quixote have been translated into nearly 150 languages, but if we only count languages that have a translation of the whole novel, then that number falls below 80 (and possibly even under 50). That’s no less impressive, though, given that Don Quixote has some 350,000 words in Spanish.

-

Sherbet lemon revisited (Reader Mail)

One of our readers, Chen, reached out recently with questions about the translation of sherbet lemon (addressed in a previous post).

First: Chen pointed out that Dumbledore “unsticks” two sherbet lemons only moments after offering them to McGonagall, and wondered how this was handled in languages that translated it as a beverage or as ice cream. Here’s some of what I found, starting with Turkish as I did in the previous post:

“Limon şerbeti. Muggle’ların bir çeşit tatlı içeceği. Hoşuma gidiyor.” … Profesör McGonagall ürktü, ama o sırada iki limon şerbeti açan Dumbledore farkına varmadı bunun.

HARRY POTTER VE FELSEFE TAŞI (Ülkü Tamer, Turkish)

“Lemon şerbeti. It’s a kind of Muggle soft drink. I enjoy it.” … Professor McGonagall was startled, but Dumbledore didn’t notice it just then, opening two lemon juices.The translator, Ülkü Tamer, indeed took into account that it doesn’t make much sense to “unstick” two soft drinks. Instead, Dumbledore opens the soft drinks. Other translations that made it into a drink tend to take this same approach. Take, for example, Isabel Fraga’s Portuguese:

“É uma bebida dos Muggles de eu gosto muito.” … A professora McGonagall vacilou, mas Dumbledore, que estava a abrir duas limonadas, pareceu não dar por isso.

HARRY POTTER E A PEDRA FILOSOFAL (Isabel Fraga, Portuguese)

”It’s a Muggle drink that I’m really fond of.” … Professor McGonagall hesitated, but Dumbledore, who was opening two lemonades, seemed oblivious.I’m almost disappointed, honestly, that nobody decided to have Dumbledore pouring a drink instead of opening presumably prepackaged cans!

Take a look at what Amik Kasuroho does in Albanian after making sherbet lemon into lemon ice cream (akullore me limon):

Profesoresha MekGur u drodh, por Urtimori, që po i hiqte letrën akullores me limon, sikur nuk e vuri re.

HARRY POTTER DHE GURI FILOZOFAL (Amik Kasuroho, Albanian)

Professor McGurr shivered, but Urtimore, who was removing the packaging from the lemon ice cream, didn’t seem to notice.The original Italian translation takes a similar approach:

La professoressa McGranitt trasali, ma Silente, che stava scartando un ghiacciolo al limone, sembrò non farvi caso.

HARRY POTTER E LA PIETRA FILOSOFALE (Marina Astrologo, Italian [2001])

Professor McGonagall started, but Dumbledore, who was unwrapping a lemon popsicle, seemed not to notice.According to Chen, earlier editions of the Simplified Chinese translation (Su Nong and Cao Suling) had Dumbledore “unsticking” lemon ice cream popsicles (柠檬雪糕), but this was updated to lemon sherbet candy (柠檬雪宝糖).

Sherbet Balls

Candy from Honeydukes, as imagined by Universal Studios at its Harry Potter theme park. Second: Chen also noted that in Prisoner of Azkaban, Ron mentions “sherbet balls” that cause you to levitate as they fizz in your mouth:

“—and massive sherbet balls that make you levitate a few inches off the ground while sucking them,” said Ron.

HARRY POTTER AND THE SORCERER’S STONE (US)The sherbet balls make another appearance later in the book when Harry shows up at Hogsmeade.

There were shelves upon shelves of the most succulent-looking sweets imaginable… there was a large barrel of Every Flavor Beans, and another of Fizzing Whizbees, the levitating sherbert balls that Ron had mentioned.

HARRY POTTER AND THE SORCERER’S STONE (US)Simplified Chinese originally translated the two instances separately, the first time as an ice cream ball (冰糕球) and the second time as a fruity juice beverage (果子露饮料). In a later revision, the discrepancy was fixed, but they became a “fruit juice cream jelly” (果汁奶冻球).

I own only a few copies of Prisoner of Azkaban in other languages. I took a look and found that most of them caught connection between the two occurrences and translated them consistently. German, for example, calls them Bausekugeln in both instances. None of them connect the “sherbet balls” to the “sherbet lemons” in Philosopher’s Stone or Chamber of Secrets as the original English does.

Only one PoA translation I have access to appears to have neglected it: Faroese (Gunnar Hoydal).

“—og stórir limonadubollar, sum lyfta teg fimm sentimetrar uppfrá, tá tú sleikir teir.”

HARRY POTTER OG FANGIN ÚR AZKABAN (Gunnar Hoydal, Faroese)

“—and big lemonade balls, which lift you five centimeters high as you lick them.”Note, by the way, the odd fact that sherbet balls are translated limonadubollar as if referencing the sherbet lemon in Philosopher’s Stone. Actually, Hoydal translates sherbet lemon as pulvursitrón (roughly meaning lemon sherbet). It’s unclear why Hoydal chose to change “sherbet” to “lemonade.”

Here’s how it’s referenced in Hogsmeade:

…tað slagið av bommum, sum Ron hevði tosað um, við sterkum pulvuri uttaná

HARRY POTTER OG FANGIN ÚR AZKABAN (Gunnar Hoydal, Faroese)

…the type of candy that Ron had talked about, with strong powder insideWe could assume this is referring to the limonadubollar, but there’s nothing in the text that connects it to Ron’s earlier mention.

As always, we love this sort of feedback. Thanks to Chen for sharing! If you have anything to add, or any questions to ask about Harry Potter, translation, or linguistics, feel free to write to us. -

[PB Bite] Low-resource languages: what they are and why they matter

This article is a PB Bite summary of the main article, Lᴏᴡ-ʀᴇsᴏᴜʀᴄᴇ ʟᴀɴɢᴜᴀɢᴇs: ᴡʜᴀᴛ ᴛʜᴇʏ ᴀʀᴇ ᴀɴᴅ ᴡʜʏ ᴛʜᴇʏ ᴍᴀᴛᴛᴇʀ.

Takeaway: Some languages are not well-equipped for education. But foreign literature in translation can help.

Terms, Concepts, & Definitions:

- low-resource language: languages that lack a large amount of literature.

- natural language processing: type of artificial intelligence used in machine translation and modeled after human language processes.

Natural language processing studies large amounts of literature to get a sense of language. But only a handful of languages in the world have enough literature. That means information about modern medicine, finance, tech, and other essential topics cannot quickly and easily be taught or transferred to speakers of most languages.

Foreign literature in translation: Translating works like Harry Potter into these languages help lay the groundwork for making new topics more readily accessible. World-building novels:

- add to the corpus of literature

- expand vocabulary

- teach children to read and write

- teach teachers how to build knowledge and communicate

Learn more here.

-

Diglossia and literacy: Arabic as example

In its most simple articulation, diglossia refers to using two languages for everyday matters. (For foundational studies on diglossia, see Ferguson 1959 and Fishman 1967.) It occurs in a language community whose core members speak two languages (or language varieties) to one another.

The reasons for diglossia vary. In India, for example, many people use both Hindi and English as the result of a prolonged domination by the British. But in the Arab world, speakers use two varieties of Arabic, that serve as assertions of authority and familiarity.

This article will focus on the latter situation where speakers use two forms of the same language. But it will first address concepts such as “Low varieties” (L-varieties) and “High varieties” (H-varieties) and the related topic of overt prestige vs. covert prestige. We will then discuss the implications for literary culture, especially as it pertains to education, literacy, and access to information.

In closing, we will illustrate with examples taken from the children’s book series, Harry Potter, which is written in the High variety of Arabic despite children’s low proficiency in that variety.

Low variety vs High variety

Low variety or L-variety: a language or language variety used in informal settings. It’s likely to be acquired at home and enjoy some level of covert prestige (see below).

High variety or H-variety: a language or language variety used in formal settings. It’s likely to be acquired through education than in the home and enjoys some level of overt prestige.

Switching between the L-variety and the H-variety does not depend solely on whom you’re talking to. There may be people you speak to exclusively in the H-variety, but it’s rare that you’d speak to anyone solely in the L-variety. In many cases, switching between varieties can happen in the same conversation depending on domain (i.e., topic) you’re discussing. An Arabic speaker, for instance, might use the L-variety with a friend when talking about their families, but then switch to the H-variety a few minutes later when discussing politics or business with that same friend.

Overt prestige vs. covert prestige

(For foundational studies on overt prestige and covert prestige, see Labov 1966 and Trudgill 1972.)

Overt prestige: positive attitude toward the use of language in ways that conform to standard norms.

Overt prestige tends to be associated with education, class, or high status. In diglossic situations, the H-variety usually has overt prestige within the language community.

Covert prestige: positive attitude toward the use of language in ways that are associated with certain values, status, or relationships, against the more widely accepted social norms.

This is perhaps most evident in the use of slang, especially by speakers who are proficient in the standard language. The preference for slang in such cases reflects, in part, the attitude that the use of standard language is haughty or pretentious in that particular sitaution.

Overt prestige and covert prestige in Arabic diglossia

Now we’ll continue with an example of how the distinction between overt prestige and covert prestige can guide the choice of speakers in diglossic communities.

I once observed a well-educated Arabic speaker use a wide range of H-variety Arabic and L-variety Arabic within a short span of time. At work—a prestigious job—he used the H-variety. It signaled authority, education, and the ability to “level” with all segments of society, including the upper class: overt prestige. The word aqūl, “I say,” was pronounced with the q as a uvular stop.

At home he spoke the L-variety, an urban dialect that came very naturally and reflected the speech his parents used when he grew up. The q in the word aqūl was pronounced just like “k” instead of the distinct uvular stop, making it homophonous with akūl, “I eat.” But with his close friends (whom he worked with) he spoke an even Lower variety, a rural dialect that was considered very harsh and unsophisticated. The word akūl (“I eat”) was pronounce achūl, with the k pronounced as “ch” in English—distinguishing it from aqūl (“I say”) pronounced as akūl.

Pronunciation of “I say” Pronunciation of “I eat” H-variety (formal) aqūl akūl L-variety (familiar) akūl akūl L-variety (vulgar) akūl achūl Distinction of “I say” v. “I eat” in the H- and L-varieties of an Arabic speaker. Note that this data has been simplified to benefit the reader’s comprehension. Even his family would have found this L-variety vulgar and inappropriate. But he and his friends used it with each other because it signaled openness and comfort. Among his friends, this vulgar L-variety had covert prestige.

Education and literacy in diglossic communities

It’s often the case in diglossic communities that the H-variety serves as the language of instruction in schools. It becomes the most accessible language for reading and the source of information, even though children might not have as much proficiency as they would with the L-variety.

On the one hand, education in the H-variety has many benefits. Generally speaking, the H-variety tends to be more widely known outside of the language community. Common H-varieties like English, French, or Standard Arabic are each spoken in dozens of countries, for example. The H-variety also tends to have a greater amount of literature, educational material, and legal and business applications. So education in the H-variety often provides students with better opportunity and potential for growth.

Attempts to promote education in Arabic L-varieties have historically been met with backlash for this reason. Such attempts were perceived as cutting off children from the rest of the Arab world and centuries’ worth of literature.

On the other hand, education in the L-variety makes knowledge more readily accessible. Because students have greater proficiency in the language they speak at home, the information is easier to understand in the L-variety than if it were presented in the H-variety.

Indeed, despite the great body of literature available in the H-variety of Arabic, few Arabs ever read books outside of school precisely because it’s not an enjoyable experience for them. The decline in Arab readership—especially out of preference for English and French among much of the educated—has led to concerns that Standard Arabic may actually die out in just a few generations. So there’s growing debate today about whether it’s even worth it to educate children in the H-variety of Arabic.

Examples from Arabic: Harry Potter

Let’s illustrate how things play out in Arabic’s diglossia, using examples from children’s literature translated from English.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone is a good example in part because, if you’re reading this article, then you probably already know the story of Harry Potter. It’s also useful because it’s written in an informal style in English but translated into a somewhat erudite variety of Arabic.

Below, I’ll provide the passage in the English original, then in the Arabic translation, and then I’ll render the Arabic into English in a way intended to highlight the difference from the English original. We’ll see that a lot of the playfulness and colloquialism of the original has been lost in translation, making it a bit more boring in Arabic.

English (original) “Oh, are you a prefect, Percy?” said one of the twins, with an air of great surprise. You should have said something, we had no idea.” Arabic قال أحد التوءمين وكأنه فوجئ: آه، هل أنت من رواد الفصول يا (بيرسي)؟! كان يجب أن تقول لنا. ليست لدينا أي فكرة English rendering of the Arabic One of the twins said, as if he were surprised: “Oh, are you among the class mentors, Percy? Would that you had told us. We had not had the slightest of ideas.” This passage mocking Percy reminds me a bit of when I read Shakespeare as a kid. There were a lot of cutting insults, but they didn’t really register with me: they were just too wordy and too formal and my attention was set on figuring out the meaning of the words.

English (original) “He’s just made that rule up,” Harry muttered angrily as Snape limped away. “Wonder what’s wrong with his leg?”

“Dunno, but I hope it’s really hurting him,” said Ron bitterly.Arabic تمتم (هاري) بغضب بينما (سنايب) يبتعد وهو يعرج: “لقد اخترع هذه القاعدة الآن.. ترى، ماذا حدث لقدمه؟

قال (رون) بمرارة: “لا أعرف.. وإن كنت أتمنى أن تؤلمه حتى الموتEnglish rendering of the Arabic Harry muttered with anger while Snape went away, limping: “He indeed has contrived this rule just now.. Oh wonder, what has come upon his foot?”

Ron said with bitterness: “I do not know.. I hope that it be hurting him to death.”Hopefully the English rendering here gives you an idea of how silly the dialogue in Harry Potter would sound if children actually spoke this way.

English (original) “Never,” said Hagrid irritably, “try an’ get a straight answer out of a centaur. Ruddy stargazers. Not interested in anythin’ closer’n the moon.” Arabic علق (هاجريد) غاضباً: “لا يمكن أن تحصل على إجابة صريحة من هذه المخلوقات.. إنها لا تفكر إلا في القمر وما حوله English rendering of the Arabic Hagrid commented angrily, “It is not possible to obtain an honest answer from these creatures. For they ponder not except on the moon and what surrounds it.” Lastly, in this example, Hagrid has lost all traces of a dialect. In fact, he speaks somewhat poetically!

-

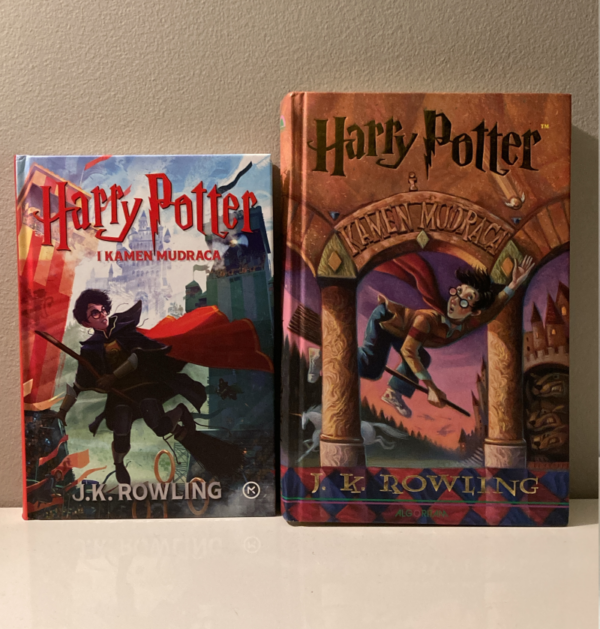

Some observations on Croatian Harry Potter: old vs new translations

The tail end of 2022 saw the latest official translation of Harry Potter—and according to how many collectors count, it’s the 100th! It was a second translation of Croatian (and the first book to be printed with the Studio La Plage cover art). The first Croatian translation has been out of publication for several years.

After being one of the first people in North America to get my hands on a copy (thanks to Sean McA.), I took a quick look through both translations and made a few observations about the differences in translation. My first impression is that both translations are enjoyable, reader-oriented adaptations, but that Petrović lends more character to the translation.

Switching Translators

The first Croatian translator of the Harry Potter series was Zlatko Crnković. Crnković was a prolific translator of novels into Croatian. He translated Lord of the Rings, capturing all those neologisms of Middle Earth, and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, creatively adapting Yiddish terms that were much easier for English speakers to grasp than Croatians. The Harry Potter series was merely the latest best-seller in his decades of publication. But as the series continued to expand—and take a demanding toll on translators—he decided to devote his attention to other projects. After all, he had been officially retired since 1994.

He worked with Dubravka Petrović, the woman who carried out the translation of the rest of the series from Goblet of Fire to Deathly Hallows. He lent her advice and feedback, continuing to leave his mark on the series even while Petrović molded it in her own image. The last of the books, Harry Potter i Darovi smrti, was published in 2007.

A few years ago, Mozaik knjiga bought the publishing rights for Harry Potter in Croatian. But before running new prints of the books, Mozaik knjiga sought to strengthen the consistency of the translation throughout the series. Some 25 years after Petrović finished with Harry Potter, the publisher commissioned her to retranslate the first three books and revise the last four.

Although Crnković had a knack for eloquence and Croatian frill in his translation, Petrović prefers to shed the classical constraints on the storytelling.

Zlatko Crnković was a master of the archaic tone, but I believe that the book must have a more modern language, because the language of the [English] original was modern.

Interview with Petrović at Književne KritičarijeIn translating the last four books of the series, Petrović wanted to respect the foundation laid by Crnković and follow his lead. That made the transition between translators smooth, even if there was a gentle shift in style.

Now she has the chance to make the series her own, not only by lending her style to the early installments, but also by revising the last four in a way she prefers.

The Changes

Petrović was clearly cognizant of the mark Crnković made on Harry Potter fans in Croatia.

Crnković’s word for Quidditch, “Metloboj” (lit. “Broom Combat”), was kept, as was his word for Muggles, “bezjaci” (lit. “twits”). But while she retained some of these more iconic terms, she changed others. Remembrall, for example, was changed from the flowery Nezaboravak (“Forget-Me-Not”) to the more literal Svespomenak (“Remember-All”).

The differences between the translations that I found most illustrative were in the first chapter. One reason that may be is because the tone of Crnković’s translation of the first chapter strays from that of the English original. Petrović’s translation attempts to restore the tone, even though that required her to stray from the literal meaning a bit more than Crnković.

Take a look at the opening sentence:

Crnković Gospodin i gospođa Dursley, iz Kalinina prilaza broj četiri, bili su ponosni što su normalni ljudi da ne mogu biti normalniji i još bi vam zahvalili na komplimentu ako biste im to rekli. (Translation) Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of Number Four Kalina Drive, were proud of being normal people who couldn’t be more normal and would thank you for the compliment if you told them so. Petrović Gospodin i gospođa Dursley iz Kalinina prilaza broj četiri doslovce su pucali od ponosa zbog činjenice da su u svakom pogledu bili savršeno normalni ljudi i veći kompliment od toga nisu mogli ni zamisliti. (Translation) Mr. and Mrs. Dursley of Number Four Kalina Drive were literally bursting with pride at the fact that they were perfectly normal people in every way and they couldn’t imagine a higher compliment than that. Here, I personally prefer Petrović’s translation choices because of its more intimate imagery on how the Dursleys feel. That more accurately (and creatively) captures the English original, where Chapter 1 is told through the perspective of Mr. Dursley.

Compare also with this selection:

Crnković …jer su njezina sestra i niškoristi muž bili sasvim oprečni Drusleyjevima. (Translation) …for her sister and worthless husband were quite the opposite of the Dursleys. Petrović …prvenstveno zato što su spomenuta sestra i njezin beskorisni muž u svakom pogledu bili potpuna suprotnost Dursleyjevima. (Translation) …primarily because said sister and her useless husband were the complete opposite of the Dursleys in every way. Again, the over-the-top approach by Petrović more effectively reproduces the Dursley-centric perspective here. The cherry on the top is the repetition of the phrase “svakom pogledu” (“in every way”), which was also used in the opening sentence. That signals to the reader that the views expressed in both sentences belong to the Dursleys. The repetition of “svakom pogledu” lends the Dursleys voice.

Let’s take a look at another example:

Crnković Za večerom mu je ispričala sve o tome kakve probleme ima njihova prva susjeda sa svojom kćeri, i kako je Dudley naučio još jednu riječ (‘Neću!’) (Translation) At dinner, she told him all about the problems their next-door neighbor had with her daughter, and how Dudley had learned another word (“I won’t!”) Petrović Za večerom mu je ispričala sve o problemima gospođe Prve Susjede s njezinom kćeri i izvijestila ga da je Dudley naučio novu riječ (“Neću!”) (Translation) At dinner, she told him all about Mrs. Next-Door Neighbor’s problems with her daughter and informed him that Dudley had learned a new word (“I won’t!”) This again illustrates the difference between the formal writing of Cnkrović and the more flexible writing used by Petrović, who uses the more literal translation of “Mrs. Next Door” (“gospođe Prve Susjede”) instead of the more standard Croatian rendering used by Cnkrović.

There are times, of course, that Crnković actually does a better rendering of the English original. But in at least some of these cases, Petrović comes up with pretty clever alternatives:

Crnković Limunov šerbet. To su vam bezjački slatkiši koje ja jako volim. (Translation) Lemon sherbet. They’re Muggle sweets that I really like. Petrović Šumeći bombon od limuna. Bezjački slatkiš koji mi je prilično prirastao srcu. (Translation) Fizzy lemon candy. Muggle sweets that are close to my heart. Petrović’s translation does two things in this example that I especially appreciate. This is the only translation of “sherbet lemon” I’ve come across that’s descriptive: she finds a way to communicate to the reader that the candy fizzes in your mouth. Secondly, the translation of “Sweets that are close to my heart” brings out Dumbledore’s character in a unique and inventive way.

Of course, what matters most in the end is whether Harry Potter fans in Croatia take to the new adaptation. So far, in the few months that have passed, chatter on the internet has been a bit quiet. Here’s a little bit of discussion that went on in anticipation of the new translation, but also a few comments about it after it was released.

-

[PB Bite] Dumbledore’s favorite: sherbet lemon, lemon sherbet, and lemon drops

![[PB Bite] Dumbledore’s favorite: sherbet lemon, lemon sherbet, and lemon drops](https://potterofbabble.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/sherbet_lemons_2-600x393.jpg)

This article is a PB Bite summary of the main article, Dᴜᴍʙʟᴇᴅᴏʀᴇ’s ꜰᴀᴠᴏʀɪᴛᴇ sᴡᴇᴇᴛ (ᴏʀ ᴅʀɪɴᴋ?): sʜᴇʀʙᴇᴛ ʟᴇᴍᴏɴs ᴀɴᴅ ʟᴇᴍᴏɴ sʜᴇʀʙᴇᴛs.

Takeaway: Albus Dumbledore loves sherbet lemon so much that it’s the password to his office. But sherbet lemon is a candy specific to the UK. So when the story was brought to other countries—including the US—nobody knew what to call it in the local language.

Why it’s interesting: We learn a little about local sweets from around the world!

It also led to some confusion in Chamber of Secrets, where the password to Dumbledore’s office is “sherbet lemon.” The American version, for example, mentions “lemon drops” as Dumbledore’s favorite sweet, but “sherbet lemon” is the password to his office. Some other editions, like German, also make this inconsistency.Some highlights:

In Albanian, it’s lemon ice cream (akullore me limon) that Dumbledore loves.

In Iceland, he prefers to enjoy a green Sítrónukrap.

Sítrónukrap

Krembo In Hebrew, krembo gives him a taste for chocolate over lemon.

Explore more here.

-

[PB Bite] How Harry Potter differs in different languages

![[PB Bite] How Harry Potter differs in different languages](https://potterofbabble.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/cropped-icon.png)

This article is a PB Bite summary of the main article, “Tʜᴇ Dᴜʀsʟᴇʏs ᴀʀᴇ ᴘᴇʀꜰᴇᴄᴛʟʏ ɴᴏʀᴍᴀʟ, ᴛʜᴀɴᴋ ʏᴏᴜ ᴠᴇʀʏ ᴍᴜᴄʜ!”: Iᴅɪᴏᴍs, ɪᴍᴍᴇᴅɪᴀᴛᴇʟʏ.

Takeaway: Harry Potter has been translated into nearly 100 languages. The very first sentence is one of the most challenging to translate. There are more than 6 different ways that translators around the world have decided to handle it!

Why it matters: That first sentence is a good indicator of translation quality throughout the rest of the book. Is it dry? Creative? Conversational? Or just way too literal?

The Lowdown: Here are the 6 different ways “thank you very much” is translated in that first sentence—

- As “thank you very much,” literally.

- Indicates: Translator is likely from UK or US.

- Example: (Welsh) Broliai Mr a Mrs Dursley, rhif pedwar Privet Drive, eu bod nhw’n deulu cwbl normal, diolch yn fawr iawn ichi.

- As a genuine “thank you.”

- Indicates: Translation pays attention to detail, but is less light-hearted in style.

- Example: (Portuguese, Isabel Fraga) Mr. e Mrs. Dursley, que vivem no número quatro de Privet Drive, sempre afirmaram, para quem os quisesse ouvir, ser o mais normale que é possível ser-se, graças a Deus.

- By emphasizing that the Dursleys are normal.

- Indicates: Translation prioritizes the “feel” over the detail.

- Example: (German) Mr. und Mrs. Dursley im Ligusterweg Nummer 4 waren stolz darauf, ganz und gar normal zu sein, sehr stolz sogar.

- By indicating the Dursleys feel normal today.

- Indicates: Story characters have slightly different personalities in the translation.

- Example: (Japanese) プリベット通り四番地の住人ダーズリー夫妻は、「おかげさまで、私どもはどこからみてもまともな人間です」と言うのが自慢だった

- Deletion

- Indicates: Translation might skip things that are difficult to translation.

- Example: (Luxembourgish) De Mr an d’Mrs Dursley aus der Kellechholzstroos Nummer véier waren houfreg drop, soen ze kënnen, dass si ganz normal waren.

- By replacing with a more native expression.

- Indicates: Translation is more light-hearted and conversational.

- Example: (Maori) Whakahī ana a Mita rāua ko Miha Tūhiri, nō te kāinga tuawhā i te Ara o Piriweti, ki te kī he tino māori noa iho nei rāua – kia mōhio mai koe.

Read more here.

- As “thank you very much,” literally.